“Ain’t nothing like ’em nowhere,” claims the slogan of Dreamland Bar-B-Que. It’s a bold assertion, yet if you ask a Southerner with an awareness of the region’s barbecue scene, or even just an enjoyment of high-quality smoked meats, it’s true.

“The barbecue sauce and the ribs are hard to beat,” Jasper native Keith Gilbert said. “I always make sure to stop in when I am in Tuscaloosa. I enjoy it too much to skip over.”

For how delectable the food might be, however, it is only half the story. Behind the hickory-smoked ribs, tantalizingly unique sauce and fan-favorite banana pudding is a rich, colorful history.

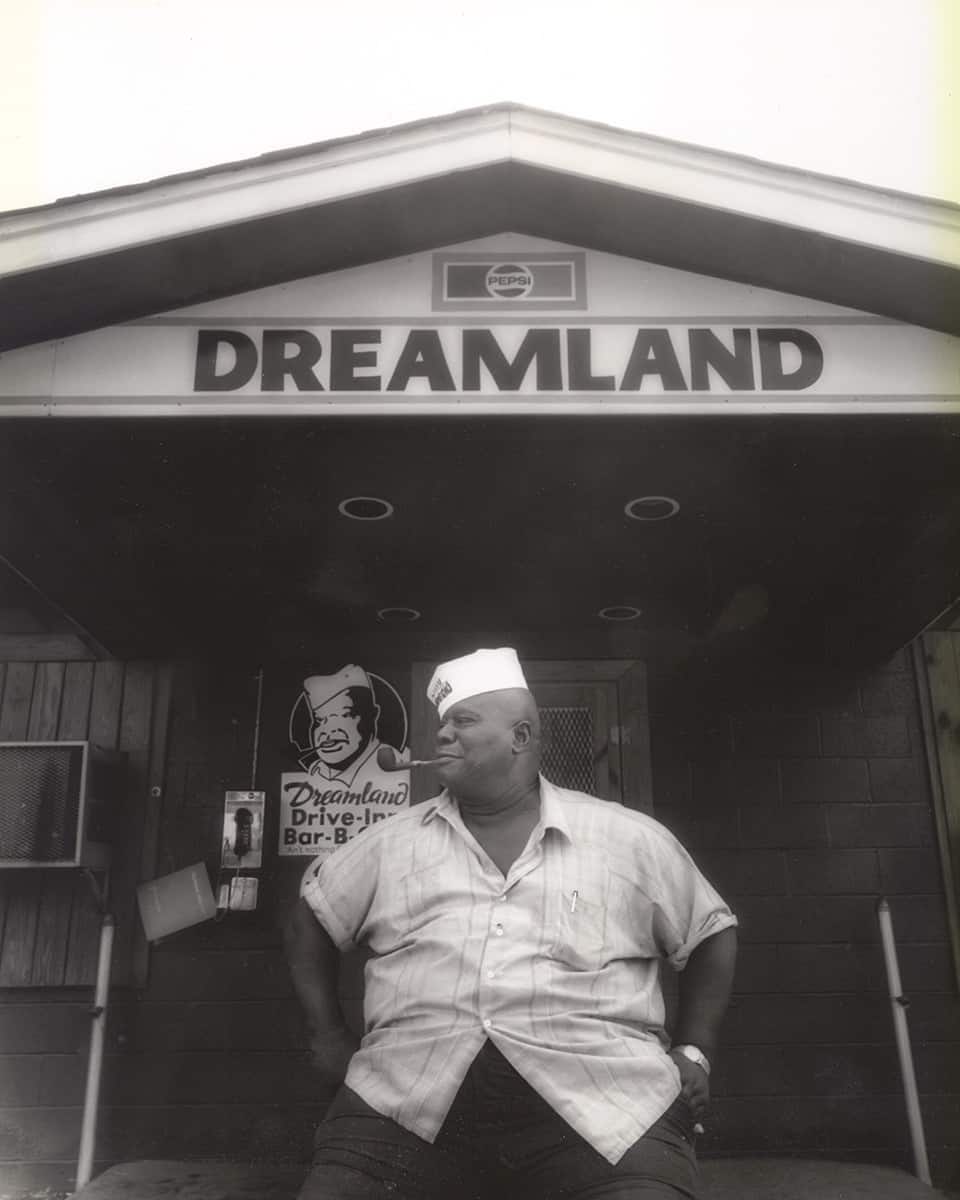

The original location, located in the heart of Tuscaloosa, radiates a classic hole-in-the-wall aura. It was opened in 1958 under the creative vision of John “Big Daddy” Bishop. This vision was apparently divine; according to the opening line of the “About Us” page of Dreamland’s website.

“It all started with a dream … and it was in that dream that God visited John ‘Big Daddy’ Bishop and told him to open a restaurant,” the website reads.

Its exterior is free from flashy imagery, more akin to a mom-and-pop shack than the famed brand Dreamland has become. The interior has a similarly niche and old-timey construction. The walls are lined with license plates, black-and-white framed pictures, signed dollar bills and other distinct iconography. Perhaps most striking is a sign with the simple imperative “no farting.”

This pioneer location didn’t immediately adopt the singular identity of a barbecue restaurant. The website’s biography details how Bishop’s eatery “sold everything from burgers to postage stamps.” It was only after the hickory-fired ribs and vinegar-based barbecue sauce became runaway favorites that such an identity was taken on.

Dreamland’s popularity spread steadily over the ensuing decades, and eventually expansion became unavoidable. In 1993, after 35 years of solitary residence in Tuscaloosa, a new location was opened in Birmingham, dubbed “Southside.” In the years since, nine new Dreamlands have popped up, expanding as far east as Duluth, Georgia, and as far south as Mobile, Alabama, and Tallahassee, Florida.

These locations have a more modern build while maintaining the classic Dreamland feel. There isn’t quite the down-to-earth feel of eating in a 1950s-style shack, but the larger and nicer venues house the same iconography and homeyness. If one visits a variety of Dreamlands, one might notice the ubiquity of the “no farting” sign; it is a small but powerful symbol of the restaurant’s small-town character despite prosperity and expansion.

The personality of Dreamland goes even deeper than the looks, even beyond the humorous signage and classic Alabamian composition.

Roscoe Hall is a renowned chef and artist who has worked in and helmed a motley array of restaurants, from David Chang’s now-closed Momofuku Ssäm Bar in New York to Rodney Scott’s Whole Hog BBQ in Birmingham. He competed in Season 18 of Top Chef.

He is also the grandson of Big Daddy Bishop, and that connection helps him provide a fresh perspective on Dreamland that’s infused with familial admiration.

“It was like home for me,” he said when asked what the restaurant meant to him. “It means a lot to the culinary world … but to me it will always just mean family.”

More than just a provider of great food, the restaurant was a unifier of sorts, bonding people of all walks of life through the universal quality of deliciousness.

While on the topic of his relationship with Dreamland, Hall intimated details of his teenage life that illustrate this unifying quality. When he first began attending St. Bernard Preparatory School in Cullman, he was one of only a few African American students. What’s more is that he was a “punk rock kid” who, thanks to the demographic skew as well as his personality, had mostly white friends.

On Friday afternoons, he would venture to Dreamland and come into the restaurant through the back door. Often, these fellow punk rock friends would come with him and follow suit.

“I would walk through with, like, a mohawk, and my friends would have, like, pink hair,” Hall remembered.

One day, his grandfather, who founded the restaurant in a time of high racial tensions, noted the unbelievable nature of it all.

“This is how far we’ve made it,” Hall recalled him saying. “I never thought I’d see white kids coming in the back door of my restaurant.”

It wasn’t only racial divides that were broken by Dreamland’s indiscriminate allure. In addition to his eccentric high school comrades, Hall recalled encountering Bo Jackson and a college-aged Shaquille O’Neal.

In these memories, Bishop’s realization rings true. Dreamland is the consummate example of a good meal breaking down barriers. The Alabama Tourism Department articulates it well: “The point is that it doesn’t matter who you are. At Dreamland everybody is special and everybody is there for the same reason — the ribs.”

This is where the real Dreamland can be found. It isn’t about the license plates or the “no farting” signs, but rather the environment the restaurant creates and the openness that environment fosters. The restaurant has its own history, but more importantly, it has lived through history as a whole and kept its character. Whether in the tumult of the ’60s or the modernity of the 2020s, it’s all about the ribs, sauce and white bread.

Such simplicity is refreshing. Life can be hard; when struggles come, however, Dreamland will be there, unchanged and with open arms, ready to serve good food to any who may come.