Fifty years ago, a group of researchers at The University of Alabama conducted a study on race relations in the wake of the desegregation movement that made the doorway of Foster Auditorium a national icon. Fifty years later, a group of researchers, some of whom were connected to previous iterations of it, carried out the survey for the sixth time.

The results indicate that while much of UA race relations has joined with the national norm, a sharp divide still exists in the perception of race relations. Celia Lo, a professor of social work at the University, said such nuanced findings were made possible by a new survey that took into account changes in the institution itself.

The survey, titled “Racial Attitudes among Students at the University of Alabama, 1963-2013,” compared data from several older surveys conducted from 1963-88 to a survey conducted in 2013. The original surveys were designed and directed by Professors C. Donald McGlamery and Donal E. Muir, both of The University of Alabama. Data for the 2013 survey were collected by the Institute for Social Science Research at The University of Alabama under the direction of Debra McCallum.

“[The survey is] pretty different from what it once was,” Lo said. “The emphasis was more the white students, whether they were accepting the minority groups.”

Lo, who worked as a graduate student on the survey when it was last conducted in 1988, said the survey, along with her research, reflects a university that no longer considers race to be only between white and black people and no longer considers relations to be solely in the classroom.

“Our survey, in 2013, has a lot more material. … the whole University is different right now,” Lo said. “My study really is about whether white students, black students, Hispanic students and Asian students have different assessments of campus race relations.”

The research indicates yes. Lo’s results found white students were most likely to have a positive outlook on race relations, while black students were more pessimistic. Lo said the results indicate these attitudes hinge not on blatant racism but “racial resentment” or “symbolic racism,” the idea that certain groups are unable to achieve high socio-economic levels because they do not personally work hard enough.

“It’s an attitude,” Lo said. “These attitudes and beliefs are more subtle.”

Racial resentment creates two separate explanations for the documented issue of minorities often having a lower socio-economic status.

“Minority groups are more likely to use structural factors to explain why blacks are poorer than the white students,” Lo said. “White students tend to see individual factors.”

Michael Hughes, a professor of sociology at Virginia Tech University who worked on the survey in 1966 and 2013, said racial resentment is a “social psychological dimension” that helps preserve racial inequality.

“While the nature of attitudes has changed, and de jure segregation is gone, a structure of racial inequality remains, and it is justified by a new set of racial attitudes,” Hughes said.

The survey indicated white UA students – at odds with the nation 50 years ago – have merged with the mainstream in racial matters, but the researchers noted it was important to view this fact in light of national race relations, which they said may not be healthy or satisfactory.

“It’s saying white students tend not to be ‘worse’ than the rest of the country,” Lo said.

Richard Fording, a professor and chair of political science at the University and researcher on the survey, said the findings empirically support what had been previously only investigated anecdotally.

“The data show that white students on our campus show similar levels of racial prejudice/tolerance to whites nationwide,” Fording said. “This is not to say that racial prejudice is absent on our campus, but that this is as much a national problem as it is a UA problem.”

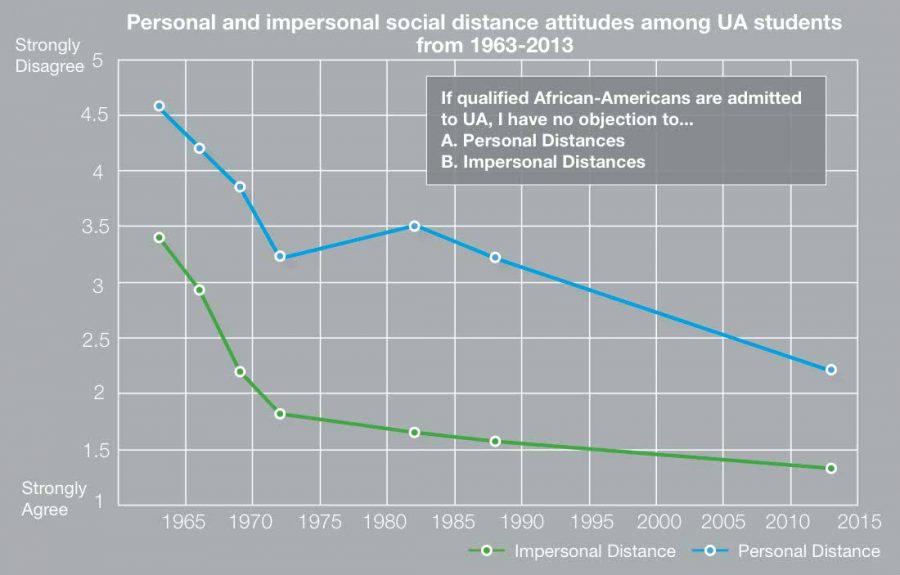

The survey also found that on average, greek students show a higher level of prejudice and preference for social distance from black students, which was the case in both 1988 and 2013. Another finding was that though overall acceptance rates were high, students were still sometimes uncomfortable with close, personal interracial interactions like cohabitation or dating.

Fording said the findings signal not the end of racial prejudice, but the end of a debate.

“As a campus community, we must now move past the debates over whether [minorities experiencing racism] is really true or widespread and start to talk about how to address it so that all of our students can have a similarly positive experience on our campus,” Fording said.

Debra McCallum, director of the Institute for Social Science Research, said the results recently presented at a symposium in Gorgas Library are just the beginning of what might be found upon further analysis, given the way in which variables of the 70-question survey might relate.

“For example, we have reported on the social distance items in terms of what objections people have to the activities, but we also asked whether they actually do these things together,” McCallum said. “These were new questions for this survey, and we have not looked at those items yet, but it will be interesting to see how they might correspond.”

McCallum said the written surveys were administered in 51 classes to more than 4,400 students in a sample that was representative of the undergraduate population.

Gabrielle Smith, a graduate student studying social psychology, said student reactions to the survey were diverse.

“We had students on both sides of the fence, either hating it and deeming it completely unnecessary, or applauding us for engaging in this research. We had very few middle of the road or indifferent reactions,” Smith said. “I think the fact that there was no uniform reaction speaks to how people are having very different racial experiences on this campus. No two experiences are the same, and I’m glad we were able to capture some of those differences.”

Smith said the nature of the research’s tangible impact on the community would depend on the community itself.

“I could see programs and classes on diversity and tolerance being instituted, or even student task forces pertaining to addressing these issues and articulating ways to make things better for all students on the campus,” Smith said. “I would be happy to be involved with those, and I think a lot of people would willingly be a part of them as well. It’s just a matter of people moving from saying things need to change to actually taking steps to make those changes happen.”

Lo said the previous research supports the idea that diversity and healthy campus race relations benefit students, especially in an increasingly globalized society; however, white students currently tend to benefit more, she said.

“It’s time to take a look at how race relations might have something to do with our students’ academic [performances] and whether they can learn or not,” Lo said. “In a college, social justice means that we will eventually have all of our students learn, benefit from the race relations and benefit from the campus climate.”

Smith said even though racial issues have not been completely overcome, she is happy to see steady progress.

“So many things in our society have changed. I think it is important to document the changes in the way we conceptualize things such as race and ethnicity as our society progresses,” Smith said. “If I take off my researcher’s hat and put on my student hat, I would say I feel pretty good about the fact that conversations are starting and there are talks of initiating change.”