Back in the mid-1950s when Paul “Bear” Bryant was the head coach at Texas A&M, he tried unsuccessfully to integrate the football team. Bryant was told by an A&M official that they would be the last team in the SEC to integrate. Bryant’s response was simple: Then that’s where they were going to finish in football.

In 1983, Bryant told B.J. Phillips of Time Magazine, “I wanted to be the Branch Rickey of college football.” Rickey was the executive who first signed Jackie Robinson in 1947. Along with Texas A&M, Bryant attempted integrating Kentucky’s football team during his tenure as head coach there but was rebuffed on multiple occasions. So instead, he recommended the black football players he wanted to recruit to schools up north.

In the late 1960s, the SEC finally integrated its football teams to stay competitive with the other schools around the country, but by then it was too late for Bryant to become the “Branch Rickey of college football.” Instead, he played a crucial role in keeping the ship steady at The University of Alabama during integration where other Southern schools floundered with the process.

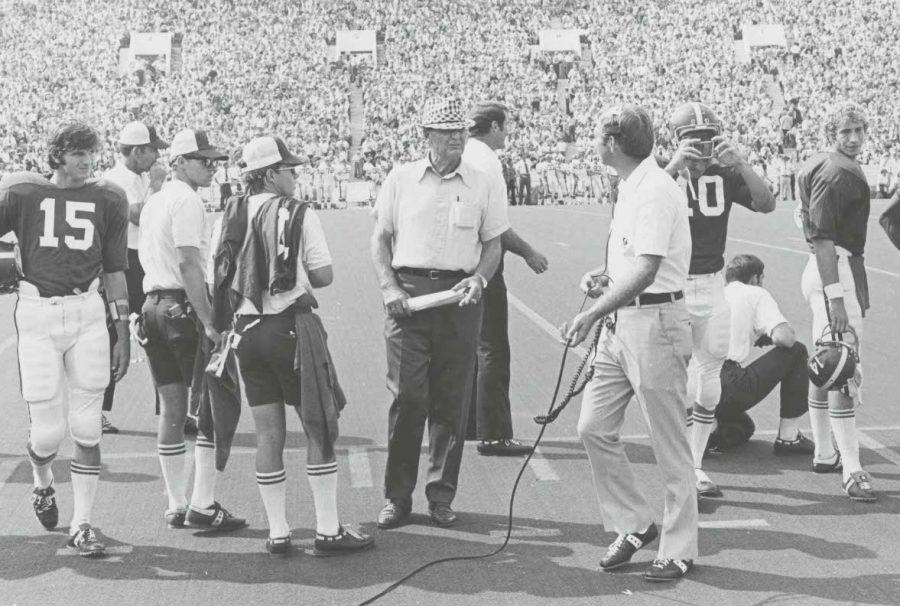

Kirk McNair, a sports information director at the University from 1970-79, said Bryant’s leadership and the atmosphere he created on the team allowed the integration process to happen smoothly for Alabama’s first two black football players in 1971: Wilbur Jackson and John Mitchell.

“All of the football players that I knew, I never knew of sort of resentment toward Wilbur, or Mitchell or any subsequent Alabama player,” McNair said. “I can’t say if it was made plain to them by coach Bryant or it was just their natural bend, but they considered anyone who was a member of the football team a full-fledged member of the football team.”

The years that followed led to a gradual but easy transition for black players coming into Alabama’s football program. According to a biography on Bryant by Mike Puma from ESPN.com, by 1973, one-third of Alabama’s starters were black.

Later that year, Alabama won its fourth national championship – and first since 1965 – putting an end to worries by Alabama fans that Bryant was getting too old for coaching. And by the time he retired in 1982, Alabama had won two national championships with completely integrated squads.

Only a month after his death, Bryant was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan, the nation’s highest civilian award. According to an archive by Texas.edu, Reagan said, “In making the impossible seem easy, he lived what we all strive to be.”

His impact may have never been as dramatized or profound as his legend seemed to be, but in the end, his contributions helped accomplish what few though would be possible.

“If there had been a lesser person at head coach, it might have been a much more difficult situation,” McNair said.