Stipends for graduate biology students are generally lower than the living wage necessary for single adults, including among UA students, a recent dataset indicates.

The dataset was primarily gathered by Michell Gaynor, a doctoral student in botany at the University of Florida, and Rhett Rautsaw, a former doctoral student and current bioinformatic scientist for PacBio. It is based on a set of crowdsourced submissions that are continuously updated and manually reviewed.

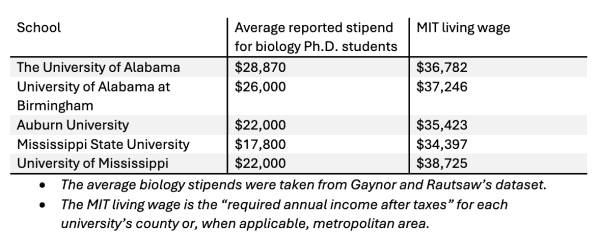

The dataset places stipends for graduate students in biology at The University of Alabama slightly above average but considerably below the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s living wage estimate for one adult with no children.

Gaynor wrote in an email that the dataset began during preparation for employee negotiations with the University of Florida, and it soon gained attention on social media when she shared some of her and Rautsaw’s initial findings.

“External benchmarking is a common tactic for stipend negotiations. After my tweet of our preliminary data, we decided to open the database to others,” Gaynor wrote.

According to the dataset, which has 213 entries across 167 universities, The University of Alabama and most other universities offer stipends below a living wage.

The University offers a variety of fellowships, research funding options and benefits like a recently expanded child care program, and based on the observations in the dataset, it ranks second among Southeastern Conference schools. However, based on the reported data, not a single SEC university’s average stipends meet or exceed the cost of living.

MIT estimates that an after-tax living wage for a single person with no kids would be $36,782 in the Tuscaloosa metropolitan area, more than $7,500 higher than the average stipend for biology Ph.D. students at The University of Alabama, according to the dataset.

Alex House, assistant director of communications for the University, wrote in a statement that this academic year, the University made “the largest single-year investment in assistantship stipends while also adding fees to the academic costs covered for graduate assistants, which includes full tuition.”

“With support from across campus, the UA Graduate School has a strategic initiative to increase base-level stipend competitiveness for graduate assistants among peer institutions in the South,” House wrote.

Gaynor and Rautsaw’s data is indicative of a wider trend across U.S. universities. A 2022 study published in American Entomologist surveyed 20 entomology Ph.D. programs and found that 17 of them paid stipends lower than a living wage. The disparity between net income and cost of living was most pronounced at Southern universities.

Similarly, several studies published since 2020 have indicated that food insecurity is a prevalent issue among graduate students.

Maryrose Weatherton, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Tennessee who studies science education and resource use by students, included Gaynor and Rautsaw’s data in a presentation to the UA biology department in February.

Weatherton said that historically, graduate students have not been paid very much.

“Most graduate students are paid for their work as teaching assistants or as research assistants, and most graduate students assume that their stipend will be their only source of income when they’re in their program,” Weatherton said. “So the size of that amount of these stipends is really important for students, as it’s basically their living wages and our income.”

She said that the size of the stipends a university offers is important in recruiting talented graduate students, adding that biology Ph.D. students typically get paid less than engineering students but more than those in non-STEM fields.

Weatherton emphasized the fact that the dataset specifically uses the living wage estimate for a single adult with no children.

“The reality of that situation is that the living wage is likely to be even higher for most graduate students, meaning that their stipend is able to fulfill that [their expenses] even less,” Weatherton said.

The disparity between stipends and the cost of living aligns with historic and current trends of graduate students and contingent faculty struggling to make a sufficient living in Tuscaloosa, including many workers who have struggled to pay for health care costs.

Weatherton said that low stipends can sometimes have disproportionate effects on historically marginalized groups.

“What we see is that within higher education, we’d see that graduate degrees are more likely to be awarded to folks with higher privilege, white folks, folks from a higher socioeconomic status. … I believe it is a really important factor of why we see a lack of diversity as we continue on in academia from undergrad to grad to faculty,” Weatherton said.

Emily Brock, a UA Ph.D. student in biology, said that although one of the reasons she came to the University was because it provided a better stipend than some other SEC schools, her stipend generally pays only enough to cover her necessities and saving what she can.

She also said she wishes her health care benefits were better.

“Right now, we get health care with our stipends, but we don’t get dental or vision insurance, and our copays can be pretty high sometimes,” Brock said.

In June, members of the United Campus Workers of Alabama delivered a petition to the UA System board of trustees demanding that the University extend the faculty and staff health care plans to graduate and part-time workers. Additionally, the petition demanded that the University reinstate affordable health care plans for adjunct instructors.

At the time it was delivered, the petition had more than 500 signatures.

The union also urged the University to assess its employees’ healthcare needs.

Brock, who was at Weatherton’s presentation to the department in February, said it started some interesting conversations among those in attendance.

“A lot of us, we are expected to produce papers and data that’s on par with a lot of our professors, but compared to the cost of living, you know … we’re not making a whole lot,” Brock said.

Weatherton said that when graduate students push for higher pay, outside observers don’t always understand why.

“I feel like folks often feel like we’re just asking for more money, right? We’re being really selfish. We’re being greedy. We just want more money. But that’s not the reality,” Weatherton said. “We are asking for these reforms because there’s no other way. Graduate students will not be able to survive unless we’re getting paid a living wage, which I don’t think is unreasonable.”