Each semester at The University of Alabama, junior Erin Routliffe’s days are planned out for her.

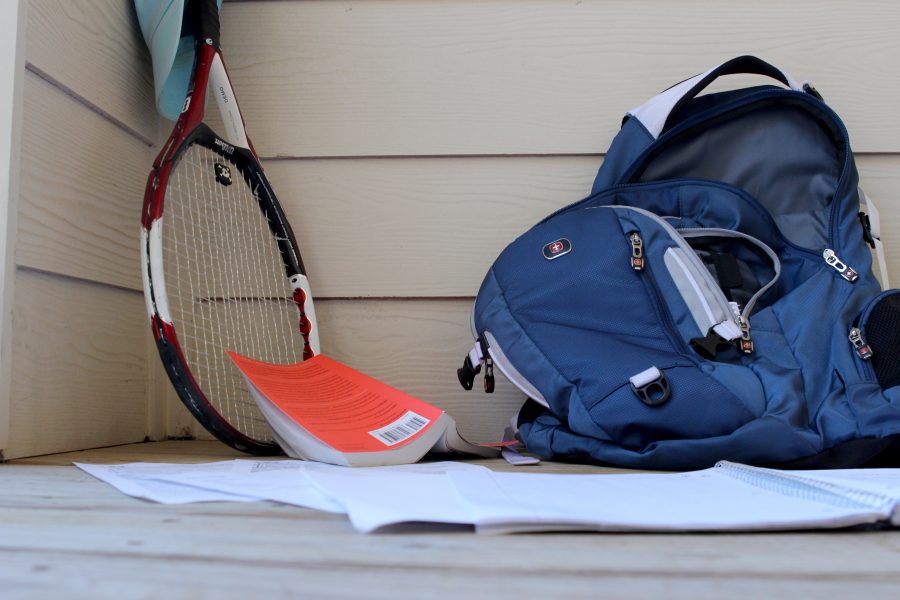

In the midst of spring athletics last year, Routliffe, a member of the women’s tennis team, woke up by 8 a.m. then took classes until noon. She practiced with her team for three hours and had individual workouts for another hour until dinner at 6:30 p.m. But, her day wasn’t over after dinner. She had study hall until at least 9:00 p.m. Then, finally, she got to go to bed, only to repeat it all the next day.

Now, the two-time defending NCAA doubles champion is early into her 2016 spring season and the cycle repeats, but the structure works and makes being a student-athlete as painless as possible.

At the collegiate level, balancing practices, matches and tournaments with schoolwork is not an easy task. This is where Jon Dever, the director of academic services for intercollegiate athletics, and his staff come in. Dever helps make this task of balancing both worlds as a student-athlete bearable.

“What we try to do is take student-athletes and balance out their practices and academic schedules in a way that promotes their success in a classroom,” Dever said. “And, ultimately, success in life.”

Most collegiate athletes won’t play professionally after college and because of this, Dever said it is part of his job to prepare them for when their sport ends and life after athletics begins.

Dever’s department provides student-athletes with resources to help ensure success in the classroom and for the future. These resources include specialized tutors, personal advisors, life skills workshops and one-on-one help with work force tools, such as resumes, networking and interview skills. During her nightly study halls last spring, Routliffe said she utilized these resources.

Once an athlete comes to Alabama, he or she is required to pick a degree. Unlike regular students, student-athletes don’t have the luxury of changing majors whenever he or she pleases. During the first couple of semesters, the athlete is allowed to change it, but once he or she starts a third year in school, the options are limited.

“The progress towards a degree is watched very closely,” said Kevin Whitaker, Alabama’s former NCAA Faculty Representative. “Athletes have to start out on a path, and then, they’re really held to that decision.”

Dever helps each athlete figure out what he or she is interested in and what major best fits that. After the major is declared, there are milestones to be met each semester.

Although the standards vary by sport, if an athlete’s GPA drops below a 2.5, Dever steps in and starts to watch that athlete’s academics more closely.

“Overall, there’s a lot of watching to be done,” he said.

Last year, Alabama’s athletes did well in academics. All of the women’s teams were above a 3.0 GPA average, and across all sports, there were only two with an average below a 3.0. Whitaker said he believed Alabama’s athletes were doing just as well in their academics as well as their athletics.

“I just don’t think we’ve blown our own horn enough about that,” Whitaker said.

The most difficult majors for athletes are nursing and education because of the student teaching that is required, Dever said. Sometimes an athlete is required to push graduation back a semester in order to meet that requirement.

Engineering, which holds 12 percent of student-athletes in its department, is also one of the harder majors to balance, Dever said.

“If an athlete comes here and they want to do engineering, they can really think about three aspects of their life: athletics, academics and social,” said Charles Karr, dean of the College of Engineering. “I tell them they can be really good in two out of the three. The right two are athletics and academics.”

Social sacrifices need to be made in order to balance everything as an athlete. Karr said regular social experience tends to be around the student’s athletic and academic program.

Dever said it is because of Karr that athletes are able to major in engineering. It is common for athletes to take classes over the summer, which helps keep them on pace for their degree, especially since they take a reduced load when their sport season is in full swing.

“It seems now that there’s actually a trend where you tend to find athletes graduate in less than four years,” Karr said.

It helps that many collegiate athletes having been involved in sports for a majority of their life and have learned over time how to time-manage well, like Routliffe, who ultimately knows that her academics and athletics come before her social life.

“It’s difficult, but you learn to manage your time really well,” Routliffe said. “You just have to have your priorities straight. We have to be on top of our grades as well as our sports.”

The NCAA has a handbook, “Mental Health: Managing Student-Athletes’ Mental Health Issues,” that lays out different topics primarily about an athlete’s mental health, such as the stresses that come with balancing everything on a daily basis.

According to the handbook, “A student-athlete may be experiencing stress because of the transition of being away from home, living in a dorm, or from academic performance in term of ‘making grades’ and becoming or staying ‘eligible.’”

NCAA also dives into different mental health issues, such as mood disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders and substance-related disorders, and what to do when a student-athlete seems to be struggling with any one of them, but NCAA’s main message is, “The health and safety of the student-athlete are always the primary consideration.”

Trying to make the whole process less stressful as possible for the student-athletes, Dever figures things out schedule-wise for athletes. In the end, all the athletes have to do is go to class and do their work, just like any other student on campus.

“As long as students don’t miss class for other reasons, I think [teachers] are very understanding about their travel schedules,” Dever said.

From her personal experience as a public relations major, Routliffe said although she has had some teachers who are stricter, most are easy to work with.

“They realize you’re representing the University and not just doing it for fun,” Routliffe said.

Professor Angela Billings in the Department of Communications enjoys having athletes in her classes. She said they’re very organized and bring an extra level of energy and excitement to the class, but she’s also a realist.

“They are individuals,” she said. “They are not their sports. It is difficult being a student-athlete not only because of the time issues of practice and competition, but they are under a lot of pressure to do well and represent the school.”

Billings said she notices that the biggest challenge for student-athletes is group projects because coordinating the student-athletes’ schedule with other students is not the easiest task. Missing class isn’t necessarily an issue because she finds that they stay on top of the work they miss. Despite the conflicts, Billings said she loves having the opportunity to teach athletes.

The reality of it is, it’s all about time management. Being in college is a balancing act for anyone, whether the student is an athlete, an intern, a director for an organization or a jobholder. The list goes on. It comes down to how hard the student is willing to work.

“Sometimes it’s really, really hard and you have to pull those all-nighters because you were at a tournament or a match, but it’s definitely worth it all,” Routliffe said.