It’s an unexpected coda to one of America’s most iconic institutions. The jury of 12 strangers, summoned by the state, emerges into the spotlight and tensely delivers the sentence before dissolving back into anonymity.

Afterward, the judge reviews the case and reverses the jury’s sentence.

These are, in theory, outliers – cases that launched themselves into the public spotlight or polarized a community, cases where a jury became an instrument of vengeance rather than justice.

In those cases, judicial override, the power of a judge to overturn a jury’s verdict, is supposed to let judges moderate the process, said Talitha Bailey, director of the Capital Defense Law Clinic.

“In theory, it was supposed to be something to assuage the passions of the community,” Bailey said. “Judges would take care of these outlier cases.”

But over the years, the state of Alabama has become the outlier in the equation when it comes to national death penalty trends, said Randy Susskind, deputy director of Equal Justice Initiative.

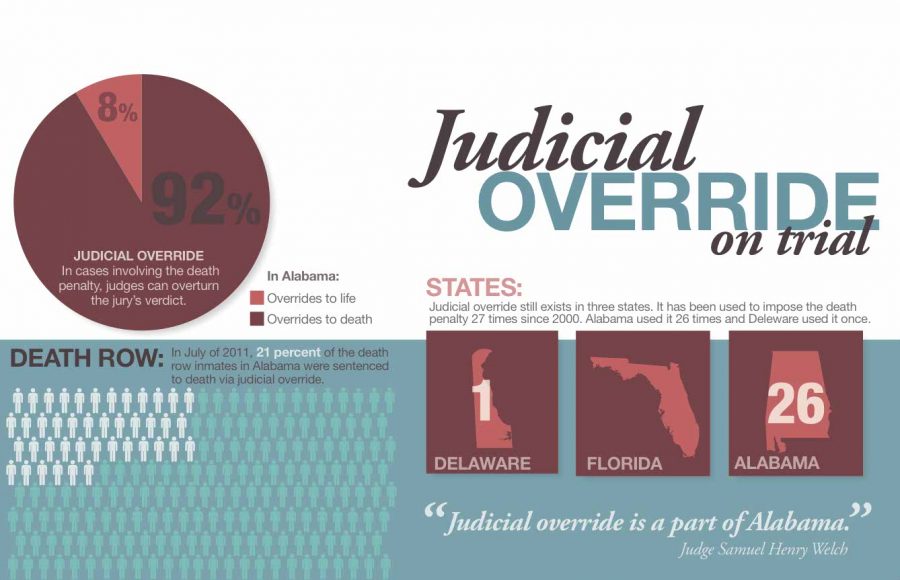

Since 2000, judicial override has been exercised 27 times, 26 of those times in Alabama, according to a 2013 Supreme Court dissent.

(See also “Roy Moore’s intolerant rants deserve no place on Alabama Supreme Court“)

A July 2011 EJI report, “The Death Penalty in Alabama: Judge Override,” refers to Alabama as the only state where judges can override decisions “without standard.”

In a nation where the death penalty is falling out of favor, Alabama sentences more people to death per capita than any other state. Susskind said judicial override has contributed to those figures. EJI’s report found that 21 percent of Alabama’s 199 death row inmates were sentenced via a judicial override.

“Our view is that overriding a life recommendation is unconstitutional,” Susskind said.

Another major figure with concerns about the state of Alabama’s capital punishment system raised similar concerns in November. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor penned a 15-page dissent upon the Supreme Court’s declining to hear a case challenging override.

In the opinion, she cited a concern about whether the use of elected judges has led to judicial politics shaping capital punishment.

Bailey said factors as basic as the capital statute (which is very broad in Alabama, meaning the death penalty can be considered in more cases) contribute to the concern.

“It was never in control. From day one, these are the results that we’ve had. The problem really is in the system,” Bailey said.

One of the biggest issues at hand, she said, is the fact that judicial overrides disregard the work of juries.

“Some of these override decisions I have read literally just say, ‘I have considered the jury’s recommendation for life and I disagree.’ And that’s it,” she said. “It’s just incredible to me that the judges would have that much disrespect for the very, very difficult work that these jurors have to do, that we ask them to do. They didn’t volunteer to sit on these cases. That’s just a shame.”

Judge Samuel Henry Welch, a UA School of Law alumnus currently serving on the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals, served as the only judge in the 35th Judicial Circuit for 18 years. He said the Supreme Court has upheld judicial override in the past.

“Judicial override is a part of Alabama,” he said.

During his service as a judge, Welch has used judicial override twice because he felt the balance of “aggravating” and “mitigating” factors, which are weighed by judge and jury, indicated the death penalty was appropriate.

Sometimes, he said, judges are privy to information a jury is not, and in Alabama juries issue advisory verdicts, leaving sentencing power to judges. Though their advisory verdicts are sometimes overturned, he said, they are not shut out of the process.

“The fact that the jury recommends life without parole is a mitigating factor,” he said.

(See also “Alabama Supreme Court overturns judge’s injunction of school flexibility bill“)

Since being upheld by the Supreme Court as constitutional, the use of judicial override has gradually dwindled. Only Alabama, Florida and Delaware still retain the mechanism.

Susskind, who called Alabama’s override system “very arbitrary,” said Delaware as a whole rarely imposes the death penalty, and Florida has since added strict rules and regulations that make override possible only in cases where a judge finds the jury’s verdict unreasonable.

Bailey said judicial override is still favorably viewed in some legal circles, but among the lawyers who come to the University’s clinic, it can be a source of devastation.

“The lawyer introduces the defendant to them in such a way that they can have mercy on this defendant,” she said. “And then to have this snatched away by a judge who doesn’t even have the courtesy to say why – when these 12 members of the community, randomly selected, show up and they’re willing to have mercy. It’s crushing for the lawyers.”

Other trends can also be reflected in judicial override figures. Susskind said there are signs of race bias, and the EJI report said 92 percent of overrides passed down by elected judges overturn a life sentence and impose the death penalty.

Bailey said this stems from the impression of judges who use the death penalty as being “tough on crime” a favorable image come election time.

However, she said the judicial override system reflects not just on judges but those who elect them.

“Nobody wants to be involved in a capital murder case,” she said. “It’s not a question of wanting to be involved in the system. It’s the fact that the system exists and it reflects on each and every person in the state of Alabama.”

Bailey and Susskind said the only fixes will come from the legislative and judicial systems, but that hasn’t stopped UA students or Sotomayor from voicing their opinions.

Andrew Grace, director of Documenting Justice at the University and co-teacher of “Anatomy of a Trial,” a class that deals with capital punishment, said he has had arguments with friends who insisted the override system could not exist as he described.

“This is a really hard concept for people to wrap their minds around,” Grace said. “I think there’s a real sobering moment when people say, ‘How is that even possible?’”

Grace helped two of his students make a documentary on judicial override and said documentaries can be a tool for helping people who might not otherwise be able to fully investigate a topic.

“Most people don’t ever sit on a death penalty case. Most people don’t have any interaction with the capital justice system at all,” Grace said. “I think a documentary is a really powerful tool to talk about the way things are and the way things should be.”

Bailey encouraged students to vote and take ownership of their surroundings.

“This is your justice system. This is not the department of corrections or some judge that’s executing people. This is the state of Alabama that’s executing people,” she said. “Whenever you’re talking about the criminal justice system, you’re talking about your state. We have to ask ourselves, ‘Is this the kind of state we want to live in? Is that what we expect from our state?’”

(See also “Court ruling could affect Alabama law“)