In 2010, 20-year-old University of Missouri swimmer Sasha Menu Courey was raped at an off-campus party by a football player. She spoke of the assault to a doctor, an athletic department administrator and a rape crisis counselor but never officially reported it to the university. No investigation was ever made, no charges were ever brought up, and Courey began falling into a deep depression. In June 2011, 16 months after she was assaulted, Courey died by suicide.

The University of Missouri is now investigating the response to that case and the issue of confidentiality and reporting sexual assault on college campuses has become a major area of discussion.

“No one in America is more at risk of being raped or assaulted than college women,” President Obama said in a speech Jan. 22, in which he announced a new initiative to investigate and combat sexual assault and harassment on college campuses.

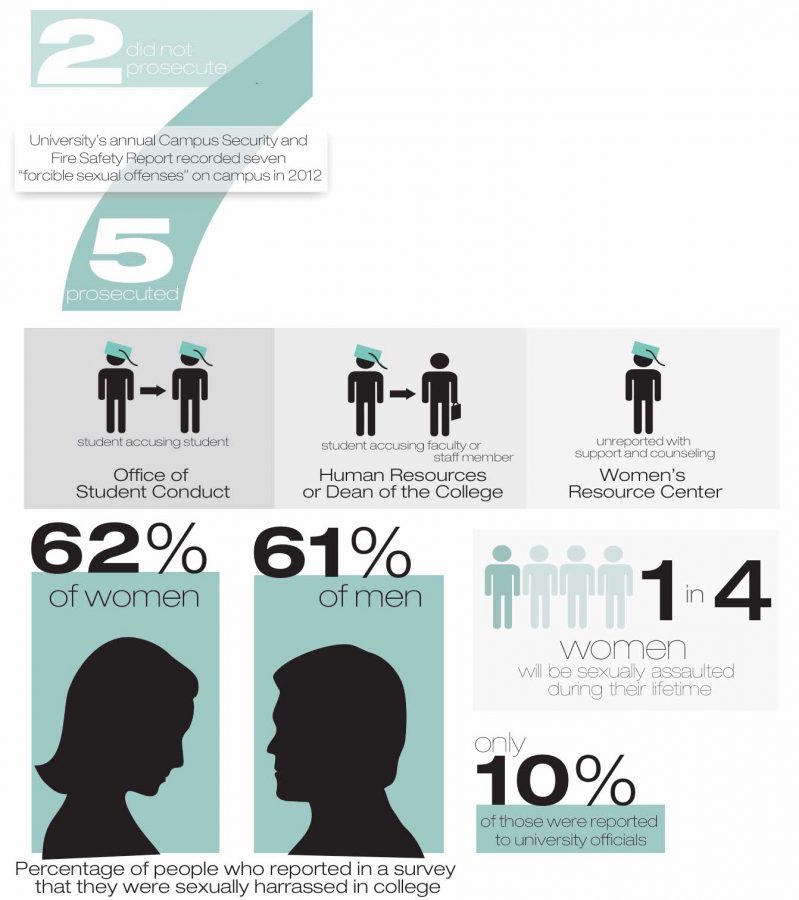

According to a survey by the American Association of University Women, 62 percent of women and 61 percent of men report being sexually harassed during their time at a college. However, less than 10 percent of this group attempts to report their experiences to a university official.

The University of Alabama’s annual Campus Security and Fire Safety Report recorded seven “forcible sexual offenses” on campus in 2012. Under the Clery Act, all colleges are required to record and disclose information about crime on campus during the course of each year. These numbers, along with all incidents of fire in residential buildings, are included in the Campus Security and Fire Safety Report.

(See also “Addressing sexual assault in college“)

“UA publishes the Annual Campus Security and Fire Safety report to make all current and future students, faculty and staff aware of any potential safety or security issues on or around campus,” said Sgt. John Hooks of the University of Alabama Police Department. “UAPD collects data from sources all over campus that are known as Campus Security Authorities. The individuals help to keep the campus safe by working with UAPD to make sure that any offenses have been properly reported and counted in our annual report.”

Hooks said a “forcible sexual offense” includes “the crimes of forcible rape, forcible sodomy, sexual assault with an object and forcible fondling.”

Hooks said any crime reported to the UAPD will be investigated and, if the victim chooses, it can be prosecuted. Of the seven offenses that were reported in 2012, five chose to prosecute, and two chose not to prosecute.

For purposes of the Clery Report, only crimes that occur on campus are included; however, the University investigates all complaints reported by students, whether against faculty, staff, another student or a stranger, through the Title IX Department.

Title IX Coordinator Beth Howard oversees all investigations and directs students to all available resources. Howard said while she doesn’t think Alabama has a larger problem with sexual harassment than other similarly sized universities, she takes every case seriously.

“One case is a problem, that’s the way we look at it,” Howard said.

(See also “Youth have to hold UA accountable for sexual assaults“)

Howard said students are under the protection of Title IX for the entirety of their time as a student, regardless of whether or not they are on campus at the time of an incident.

“The way Title IX works, anything that has to do with a student, faculty or staff member, anything like that, it’s in the jurisdiction, “Howard said. “If it’s two students or some other part of the faculty or staff and it happens on spring break or on a class trip, then we can go through the regular student conduct process. If the accused person is a regular member of the school, it’s just like if it happened here on campus.”

An investigation through Title IX can include talking with both the complainant and the accused harasser, looking for evidence through email or text communication, providing alternative housing options or moving a student to a different class.

If a student were accusing another student, the case would go to the Office of Student Conduct for a hearing. If a student were accusing a faculty or staff member, the case would be handled by either Human Resources or the dean of the college.

In addition to Title IX, each college, school and academic division has a Harassment Resource Person who can investigate accusations. Lisa Dorr, the resource person for the College of Arts and Sciences, oversees the investigation of complaints of sexual harassment, racial and sexual discrimination and disability issues.

“I see everything under the sun, all permutations. I see women complaining against men, I see men complaining against women, I see staff against faculty, staff against students, students against staff, involving heterosexual harassment, homosexual harassment. I see it all,” Dorr said.

Dorr’s “complaint compliance team” works with Title IX and conducts a full investigation of all reports. Dorr said that fears of retaliation often prevent students from coming forward to formally report instances of assault or harassment.

“As we tell people, the information is confidential and it only goes to people with an immediate need to know,” she said. “We have a very strict policy prohibiting retaliation. If the complainant feels there is retaliation because of that complaint, it’s actually almost a more serious offense against the target.”

“I think you do have to come forward and say some hard things and be willing to trust the process to work,” Dorr said. “The process, in our experience, works very well, better than many universities, and [students] need to trust the process.”

Alternatively, students who want to receive support and counseling but do not necessarily want to have the matter investigated can seek help from the Women’s Resource Center. The WRC provides counseling, support groups and victim advocacy.

Staff therapist Kathy Echols runs a support group through the WRC for women who have been assaulted or abused and also provides personal counseling to students. She said confidentiality is one of her main concerns. The WRC only turns over information to Title IX or the police if a student specifically authorizes it or in cases where a minor is involved.

“When they come in here, and let’s say they haven’t reported and they don’t know what to do, they’re confused and trying to figure it all out, what we do is actually lay out all their options,” Echols said. “Any kind of legal options, office of student conduct options if it’s another student, if they need protection from abuse orders or restraining orders, if they want to report to the police. We lay all that out for them, then we talk about things, this is how this would go possibly, these are some things that the police are going to ask you.

“They have a consent form they have to sign for us to talk to somebody so we wouldn’t just go talk to somebody without them signing a consent form,” she said. “We still want them to feel like they have control over the situation and what’s being done.”

Echols said one in four women will be sexually assaulted during their lifetime, but many are too afraid to tell anyone about it.

“The reasons that most people don’t report are: They’re afraid they won’t be believed, they’re in shock at the beginning of it and don’t know what to do, they are scared of the legal system,” she said. “They’re worried about what people are going to think, they’re embarrassed, they’re ashamed, or even feel guilty or responsible when they’re not. There’s no way you’re guilty of being raped.”

(See also “Men need to step up, have a voice in sexual consent war“)

She said that the police may ask victims uncomfortable questions in the process of the investigation, but that this is to help them understand the circumstances of the assault, and nothing that is said will reflect poorly against the victim.

“Some students are afraid to report anything that they think might get them in trouble, but that’s not an issue there. They’re not going to get in trouble – the victim is not.”

Echols stressed education is the only sure way to prevent incidents of assault and harassment.

“I think it would be a disservice to a victim to insist or encourage or try to force them to report. What I do think would help prevent some things would be bystander intervention,” she said. “Educating people to stand up. Because they don’t want to get involved. And also getting away from victim blaming. They’ll be like, ‘No, she shouldn’t have gotten that drunk. It’s her fault because she shouldn’t have been there.’ Educating people on that dynamic – it cannot be the girl’s fault. It cannot be. She is not responsible.”

This year, both The University of New Hampshire and The University of Massachusetts began implementing a Bystander Intervention education program, as mentioned in a Feb. 7 New York Times article. The program trains students to recognize potentially dangerous situations and to stop assault before it occurs.

Echols said many of her clients have lost friends after reporting being raped or assaulted, because often the victim and perpetrator are in the same friend group and other friends don’t take the victim’s side.

“[We need] society taking a stand that those things are not tolerated. Then maybe you would come forward as a victim if society was standing up saying, no, we won’t accept this. Right now society’s not saying that, so they’re afraid. We’ve been trying to talk about this for years. We’re still doing the same thing that I was reading about in 1970.”

President Obama echoed this sentiment in his speech, in which he called for increased education about bystander intervention.

“This is not an abstract issue. It affects us all,” he said. “I want every man in America to feel some strong peer pressure about how they’re supposed to behave and treat women. That starts before they get to college.”

Echols said although victims may want to keep what happened to them a secret, it can be empowering to reach out for help, whether or not they choose to have their case officially investigated.

“One thing I do know for sure in doing all this work is that victims can heal and coming forward, finding counseling, finding resources to help you work through this,” Echols said. “You can get your life back; you can take back control of your life, even though in the moment you may not feel like it. Finding those resources and reclaiming your life and not living in fear and not letting that take over, I think that’s a powerful message to send.

“One of my clients wrote, ‘This will not define me forever’ shortly after she was raped. I think that’s really powerful because we can’t stop what that perpetrator might do out here but you can help yourself. If this has happened to you, find resources and move forward.”