Relatively little attention has been paid to recently dropped docudrama “Einstein and the Bomb.” Its solid 88% on Rotten Tomatoes comes from only eight reviews; it is nowhere to be found on Letterboxd’s “Popular This Week” page; it has hovered unassumingly in the middle of Netflix’s own most popular section, and that’s likely owing to its status as recently added.

This lack of exposure makes sense. The movie is quite humble, with the simple hook of “What happened after Albert Einstein left Germany?” Such humility is perhaps its greatest gift, however — it’s unflashy, and as such its examination of history and glimpse at humanity have a sort of silent conviction. It rewards the viewer who stumbles upon it, delivering a convicting look at the bomb through the eyes of one of its most tormented contributors.

There’s a sort of encyclopedic nature to how the movie operates. It manages to do an efficient balancing job, broadly roping in all of World War II and the nuclear warfare therein while analyzing these events with an incisive point of view.

A bird’s-eye-view run-through of the buildup to World War II, both in the world of science and in the world of international politics, the film categorically attaches itself to last year’s historical behemoth “Oppenheimer.” Though the subject of Christopher Nolan’s epic is absent from “Einstein and the Bomb” — there isn’t so much as a mention of Oppenheimer’s name — the spirit of “Oppenheimer,” which is rooted in moral doubts and the nuanced horrors of the war, is palpable.

Though the overall approach to the war and its nuclear subwar is objective and broad, it is still put through the contextual perspective of Einstein, who is tortured by an inner battle between passion for peace and realization of necessity. The thematic hinge point of the film is Einstein’s apprehension over his 1939 letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning of nuclear development in Germany and urging the United States’ haste in its own such development. Einstein acknowledges that outracing the Nazis is crucial, but with the hindsight of atomic warfare and its appalling results, he is racked with guilt. It’s especially biting given that the Germans ultimately failed in their pursuits.

How this inner conflict is portrayed is where “Einstein and the Bomb” distinguishes itself from biopics like “Oppenheimer” that narrow the scope onto the psyche of one specific character.

This movie, while ostensibly focused on Einstein, manages to deal with a wide array of conflicts in a notably short run time. Its unique format as half drama, half archive footage allows it to root the story in a malleable depiction of its historical figures while also showing events in their original, unedited state. Seeing tragedies without special effects, a script or paid actors invokes a type of revulsion that can’t be otherwise replicated.

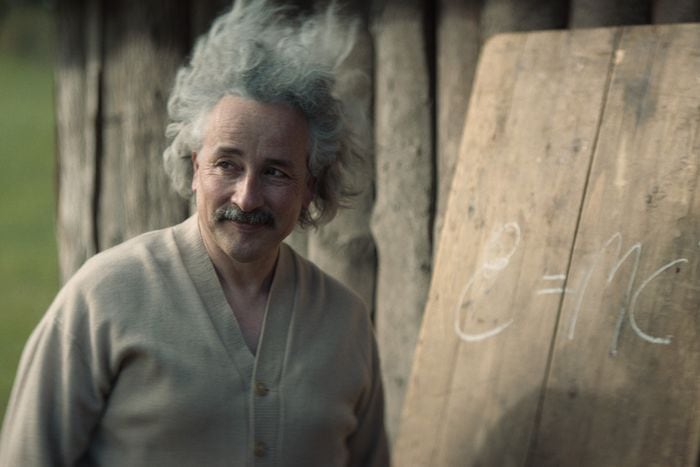

With the help of this harrowing archival footage, the film adds emotional depth to its fictional scenes. Most of these moments are quiet, featuring Einstein reflecting on his past, giddily discussing scientific theory, wrestling with his disquietude or meditating on the state of humanity. Aidan McArdle gives an admirable performance in the role, effecting both troubled silences and genuine passion for humanity, no matter how twisted its doings become.

A meek consideration of what brought these twisted doings about drives the film’s narrative. It isn’t very cinematic; even the breathtaking shots of a star-filled lunarscape are used as thematic tools, overlayed with Einstein’s wonderings about the state of the world and set alongside the horrific events of the early-to-mid-20th century. It makes for a quiet yet convicting final product.

“Einstein and the Bomb” isn’t attempting to be a world-beater. Instead, the lack of grand cinematic ambition serves a noble quest to reconcile intellectual progress with its potential abuse, national security with nauseating external consequences. What’s more, by utilizing the docudrama format, it allows for horrors captured in their rawest form to be considered and lamented over by carefully crafted scenes of biopic.

The result is a thought-provoking look at the peak of mankind’s blood-soaked ingenuity. Einstein, while the lead, is not the focal point; rather, we focus on his focus, which is locked onto the terrifying nuclear warfare he played a small part in catalyzing and the path forward from, through or hopefully out of it. Between the two titular subjects, the bomb is the true main character. Neither Einstein nor the audience has solid answers by the movie’s end, but it can’t be denied that the gentle genius is the perfect lens through which to confront the bomb’s devastating impacts.