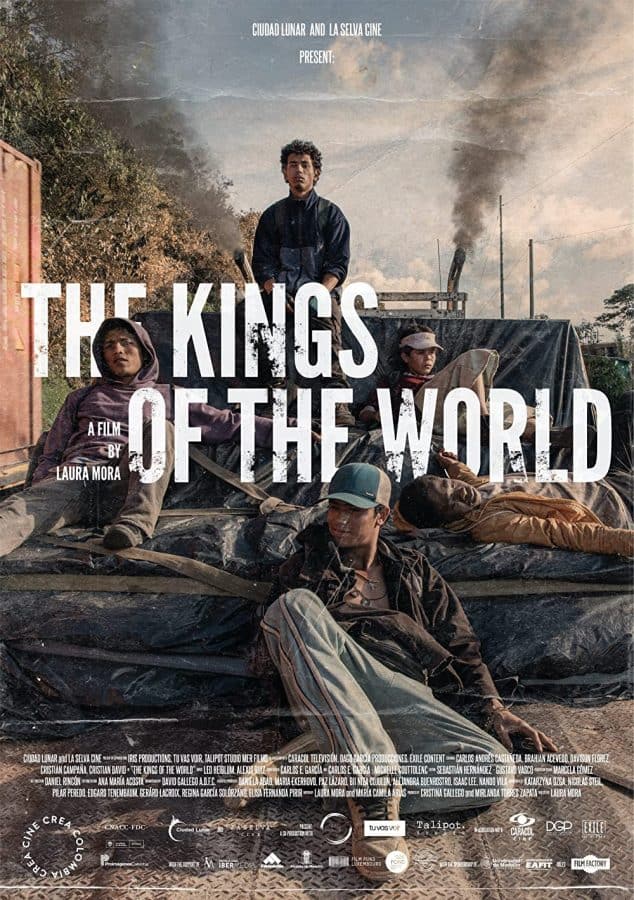

Culture Pick: “The Kings of the World” and the brutal reality of poverty

January 18, 2023

Half a decade after the release of her 2017 drama “Killing Jesus,” Colombian director Laura Mora Ortega has graced the independent film scene once more, this time with “Los Reyes del Mundo,” or “The Kings of the World.”

An unflinching examination of the brutal poverty and marginalization faced by a multitude of people across Colombia and a thought-inducing artistic endeavor, the film has opened to an 82% critics’ rating on Rotten Tomatoes. It has won six awards with three additional nominations across a slew of film festivals, including the Chicago International, the Oslo Films from the South and the San Sebastián International.

The film follows young Rá, his brother, Culebro, and three younger boys whom he has essentially adopted and taken into an interesting parental dynamic. Rá’s mother has passed, and his father has not been seen since; upon Rá’s grandmother’s death, she left him a plot of land which was restored to her after restitution agreements by the government and is allegedly full of gold.

A ragtag and chippy bunch, the five boys set out to reach this land and finally have something to call their own in a world where they have consistently been pigeonholed into the stereotype of poor, violent street kids.

It is easy to get lost in the sheer realism of it all. The journey is by no means that of a valiant knight seeking honor and glory; it is one filled with encounters and challenges that are both completely logical and, for the most part, devoid of the intensity or urgency characteristic of normal narrative fiction. It almost feels as if this is a documentary or nonfiction film.

As Manuel Betancourt of Variety puts it, “so authentic are the performances Mora has wrung out of these nonprofessional actors, so unobtrusive is David Gallego’s kinetic cinematography” that it is hard to see this as a fictitious story.

Among the stops on this journey are a makeshift hotel of sorts run by sex workers, a shed belonging to a group of menacing traffickers, and the home of an old man and social outcast. The only connective thread between the events seems to be that they are seeking shelter on their way to hopefully claiming the land.

When they finally reach their destination and hand over the papers confirming that Rá is the plot’s rightful owner, they are told that though the land is indeed his and was correctly given to him through the restitution process, the decision has been appealed and therefore must go to court once again.

“Hire a lawyer,” the boys are told: words delivered in unfazed manner from the mouth of a woman to a nineteen-year-old with no home, no parents, no real guardian, and many young boys under his care. It seems as if, after all the disjointed voyaging, it was all for naught.

While it masquerades for an hour and 15 minutes as a storiless arthouse drama in which “kids will be kids” and there’s generally no sense of direction, “The Kings of the World” employs simplistic motifs, symbolic subtleties and silence to put forth a striking moral.

Underneath all its crassness and unabashed portrayal of adolescent chippiness is a jarring portrait of marginalization; without forcing things in the slightest, it shows the hopelessness of fighting against the body, at times faceless and at times maskless, behind everything life beholds. It’s seen in the blurry mob getting ready to enforce justice on the rambunctious “kings;” it’s seen in the government employee who can simply state legal facts and provide no sympathy; it’s seen in the group of gold-diggers the boys find when they go to the plot despite being rejected foraging through land that isn’t rightly theirs.

The most devastating part about this is perhaps that it offers no solution. There is no pretense of glaring hope, no ignorant hope to remove the weight of the boys’ runtime-long naivety. It is only when death becomes certain that the fight against it becomes utterly pointless. All the aimless wandering which has filled the last two hours seems irrelevant. The boys could scream, yell, or submit the most convincing and infallible argument as to why the land is rightfully theirs. Constantly screwed by everyone and yet no one in particular, the boys have done nothing to forfeit their inheritance. But why argue, if it is no use?

In the grand scheme of things, fighting is pointless, by no means a new idea in melancholy films like this one. The gut-wrenching conclusion in “The Kings of the World,” however, is that silence is futile as well.

Juan Pablo Russo of Escribiendocine describes it as “an honest film, in which the most brutal reality mixes with a more lyrical surrealism to talk about hope, friendship, and love.”

“The Kings of the World” can be streamed on Netflix. It has an 85% Critics’ Rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a 7.2/10 on r , and a 4/5 on IndieWire.