The European Organization for Nuclear Research, or CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, started delivering data for the first time in over two years. Since the shutdown and months of recommissioning, the LHC, near Geneva, Switzerland, is now providing collisions to all of its experiments at the unprecedented energy of 13 TeV, almost double the collision energy of its first run, according to a CERN release.

“With the LHC back in collision-production mode, we celebrate the end of two months of beam commissioning,” said Frederick Bordry, CERN Director of Accelerators and Technology. “It is a great accomplishment and a rewarding moment for all of the teams involved in the work performed during the long shutdown of the LHC, in the powering tests and in the beam commissioning process. All these people have dedicated so much of their time to making this happen.”

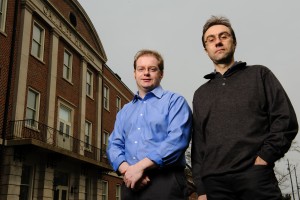

Two University of Alabama assistant professors of physics and astronomy, Paolo Rumerio and Conor Henderson, were working on the LHC when the collisions happened.

“These record high energy collisions will open up a new chapter in the story of particle physics,” Henderson said. “After discovering the Higgs boson already at the LHC, we hope these even higher energy collisions may reveal to us evidence for something new, perhaps supersymmetry or extra dimensions of space.”

This supersymmetry Henderson refers to is a theory that hypothesizes the existence of more massive partners of the standard particles we know, and could facilitate the unification of fundamental forces.

“Some of the biggest discoveries in physics have come thanks to the LHC and the scientists working on it,” said Shaun Hogan, an undergraduate physics major at the University of Alabama who works with Henderson on LHC research projects. “Nobody knows exactly what we’ll find with these new collisions, but I think it’s safe to say that something is out there waiting to be discovered.”

According to CERN, the LHC is a particle accelerator that pushes protons near to the speed of light. It consists of a 27-kilometer ring of superconducting magnets with a number of accelerating structures that boost the energy of the particles.

Since the discovery of the Higgs boson, a heavy particle believed to give mass to elementary particles such as electrons and quarks, was only the first chapter of the LHC story, the restarting of the machine, operating at double the energy of its first run, marks the beginning of a new adventure.

The LHC is expected to operate for the next 20 years.