Like other University students, Traylor is no stranger to the dining halls or the green straw sprouting from a Starbucks Frappucino. She just completed her first few weeks of college, and didn’t fail to take advantage of the Dining Dollars and meal swipes on her new Act Card.

“The thing is, you can have anything [to eat], as long as you have good control over your diabetes and you cover it with insulin,” she said. “That’s always what my doctors told me to do.”

Traylor was diagnosed at nine years old, and the disease has impacted her life beyond the foods in her diet. Diabetes is a chronic disease that affects insulin, the hormone that helps control blood sugar levels. Frequent urination, hunger and thirst can all be symptoms of diabetes, but the disease also increases risks for long-term complications like cardiovascular disease, kidney failure and blindness. The Center for Disease Control reported that 29.1 million Americans had the disease in 2012, according to the National Diabetes Statistics Report published this year.

Being a diabetic sparked Traylor’s interest in nutrition, and she is currently majoring in food and nutrition. Her goal is to work in a diabetic clinic and later as a diabetic educator, she said.

Studying nutrition has made Traylor aware of the importance of educating people about Type 2 diabetes, a disease linked to poor diet and exercise, she said.

“Type 1 diabetes is on the rise, too,” Traylor said. “But most people don’t even know what that is.”

The fundamental difference between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes is in how the body reacts to insulin. For Type 1 diabetics like Traylor, insulin-producing beta cells are destroyed by the body’s immune system. Type 2 diabetics have these beta cells, but the cells misuse insulin because they have built up a resistance over time. The beta cells then cannot produce enough insulin to meet the body’s rising needs. Type 1 diabetes is also called juvenile diabetes, and its causes are currently unknown. Type 2, also called adult-onset diabetes, is typically caused by excessive weight and insufficient exercise.

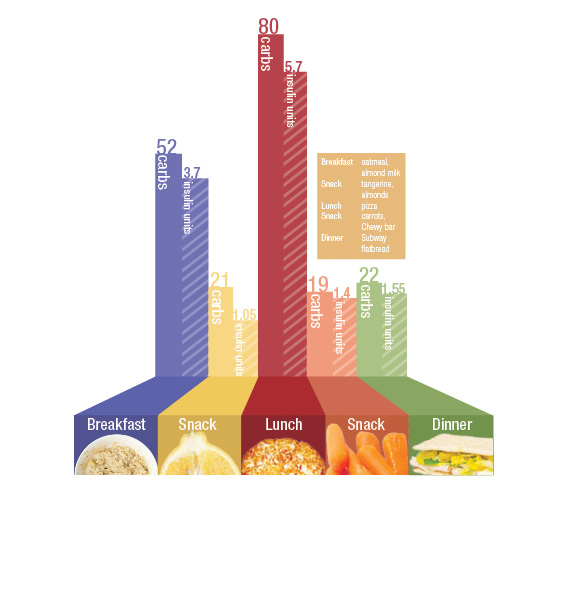

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle with Type 1 diabetes requires Traylor to constantly monitor her blood sugar levels and the carbohydrates she consumes. Each diabetic has a specific formula for discerning how much insulin is required per carbohydrate ingested.

Making the transition from living at home to being in college has prompted her to take more control of managing her diabetes. She scheduled her classes so that she could eat around the same times every day, and she keeps a dry erase board in her dorm to keep track of her health.

Bennett Bozeman, a Type 1 diabetic, graduated from the University in December 2012. He was diagnosed at 16 months old and remembered the first semester of college as being the most difficult, largely because of his class and Greek life schedules, he said.

“Managing diabetes also, I didn’t take a step back, but it just dropped off of what I would have liked to do,” Bozeman said. “I just had to refocus when I noticed that I wasn’t doing my best.”

Informing friends and having their support in maintaining diabetic health makes the transition to college much easier, Traylor and Bozeman said.

“I definitely think that the best thing you can do is to get your friends involved,” Bozeman said. “Not with emergencies, but just try to educate them, so that you can prevent emergencies.”

Periods of high or low blood sugar can be dangerous to diabetics. For Traylor, having low blood sugar is more likely. Low blood sugar results in shakiness and feeling incoherent, and drastic drops in blood sugar can lead to unconsciousness. Having friends who can recognize these symptoms is important, Traylor said. She keeps glucose tabs in her purse in the case of emergency.

In addition to making friends on campus aware, students may also contact the Office of Disability Services to meet their particular needs, said Judy Thorpe, Director of ODS. Accommodations are made once the student submits medical documentation and has a meeting with the ODS.

Though students are treated on a case-by-case basis per federal law, typical accommodations for diabetics include priority registration to make a class schedule around the medical needs of the student, permission to eat and drink during class and breaks or extended time during tests to attend to medical needs, such as checking blood sugar. Accommodation letters for students with diabetes also say that emergency personnel should be contacted via 911 should the student become unresponsive, Thorpe said.

Depending on the individual needs of the student, the ODS may refer them to other services on campus.

“We have even referred students with diabetes to the Student Health Center to get sharps containers so they can properly dispose of syringes with which they administer their medications,” Thorpe said.

Sheena Gregg, a dietician at the Student Health Center, works with students on diabetes education. She said providing upfront education to diabetics is key to preventing the potential ill effects of poor health decisions, like losing consciousness from low blood sugar.

Gregg said she helps diabetic students navigate dining halls and provides other resources to help them feel more comfortable managing their disease.

“[The SHC] talks to students about utilizing their resources to keep them in check, like using a smartphone to put reminders on their calendar of when they need to eat, and maybe already pre-planning some of those snacks and meals,” she said.

Reading nutrition labels, particularly for carbohydrates, is vital to diabetics, but the diet isn’t necessarily as restrictive as it seems, she said.

“As a dietician, I think that a diabetic diet is really how everybody should be eating, just in terms of having a modest portion size of all of the different food groups,” she said.

Students in the Honors College can take a one-hour UH 120 course titled Diabetes and Obesity: An American Epidemic to learn about the disease in an academic setting. The course was developed and led by students and features multiple guest speakers. Rebecca Kelly and Pamela Payne Foster are the advisors for the course this fall.

“The basic science of diabetes is covered, like the differences between Type 1 and Type 2, for example,” said Foster, associate professor of community and rural medicine. “There’s also an area for pre-diabetes.”

Gabby Jones, a sophomore majoring in public relations, said she has recently become interested in diabetes education. Her younger brother, Andrew Jones, a high school senior in Texas, was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in January. She is currently involved with the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, a leading organization for research regarding Type 1 diabetes.

“I just want him to be a normal college student one day and experience all of the things that I am,” Jones said.

She hopes to connect with other students on campus interested in working with JDRF, she said.

Meredith Cummings, instructor of journalism and director of scholastic media, has been living with Type 1 diabetes since her diagnosis at age 12. Recently, Type 2 diabetes has received research and publicity, and Cummings said that she hopes to see more research for Type 1.

Cummings reflected on an event from this past summer, where Sierra Sandison wore her insulin pump while competing for Miss Idaho 2014. Sandison, a Type 1 diabetic, won the crown and also gained attention with a social media hashtag, #ShowMeYourPump.

“That was pretty cool for people like me,” Cummings said. “I hide [my insulin pump] all the time.”

Cummings said she is appreciative that diabetes is a manageable chronic disease, but she said that maintaining her health is constant and relentless.

“For a college student who is trying to do well in school and adjust to either new life as a freshman in college or getting to go out into the world as a senior and get a job, relentless isn’t something they really have time for,” she said.

Like Traylor and Bozeman, Cummings informs those around her that she is diabetic, should an emergency arise. She monitors her blood sugar often, but makes sure at least one student in each class she teaches knows that she is diabetic. Cummings generally tries to be discreet in efforts to keep others from being uncomfortable, but also said checking blood sugar in public is a personal choice.

Of all the years since she was diagnosed, Cummings remembers her collegiate years as being the most difficult, she said.

“Any college student feels pretty invincible. You’re young, and this is one of the best times of your life,” Cummings said. “I wouldn’t want to take that away from anybody. I hope every diabetic student feels young and invincible.”