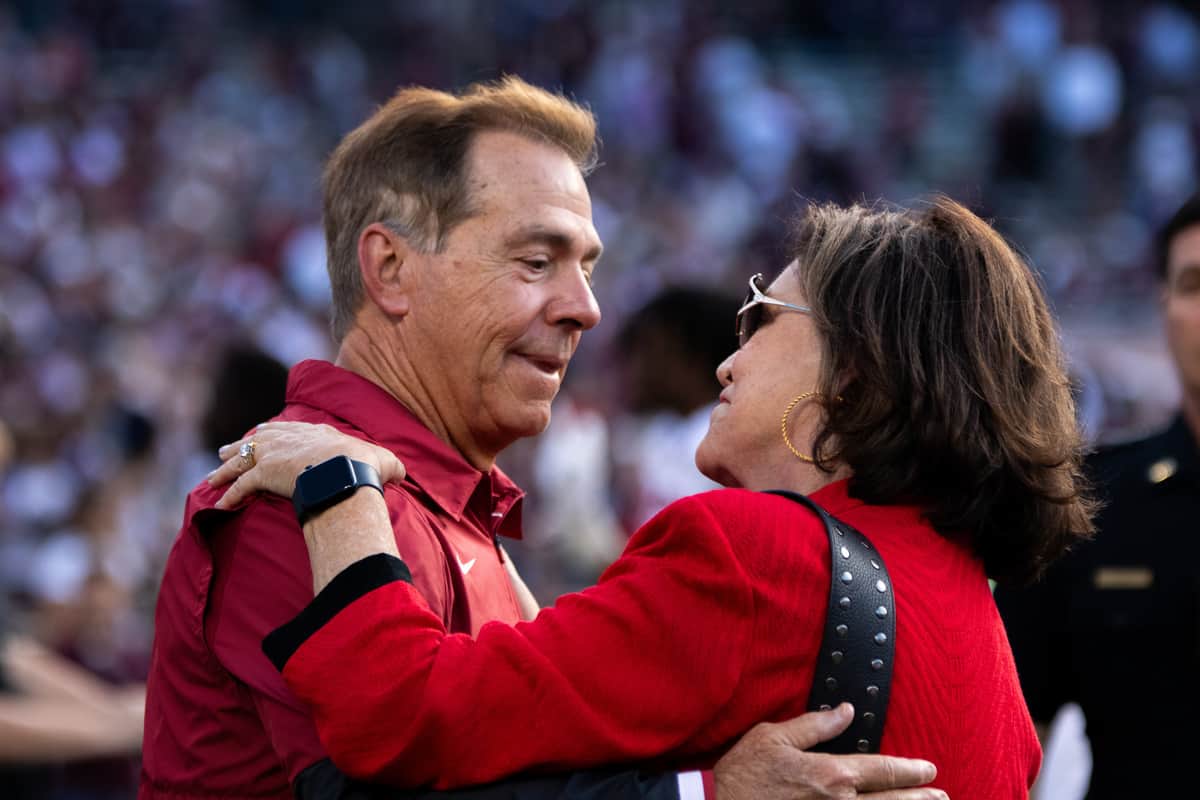

Soon after the news of Nick Saban’s retirement shook the foundations of Tuscaloosa, students at The University of Alabama flocked to Saban’s commemorative statue outside Bryant-Denny Stadium. A vigil of sorts commenced, and offerings were given; photos captured the bronze likeness of an invigorated Saban glowing under a somber dusk sky, surrounded by gifts of Coca-Cola, Oatmeal Creme Pies, game day shakers and flowers.

It was an appropriate reaction. Saban’s impact on the school and the city is difficult to overstate. The local economy in particular owes an immense debt to the immortalized head coach — his footprint on the growth of the University and Tuscaloosa is felt in a multitude of areas.

There are levels to this footprint, and there is a very logical starting point.

The program

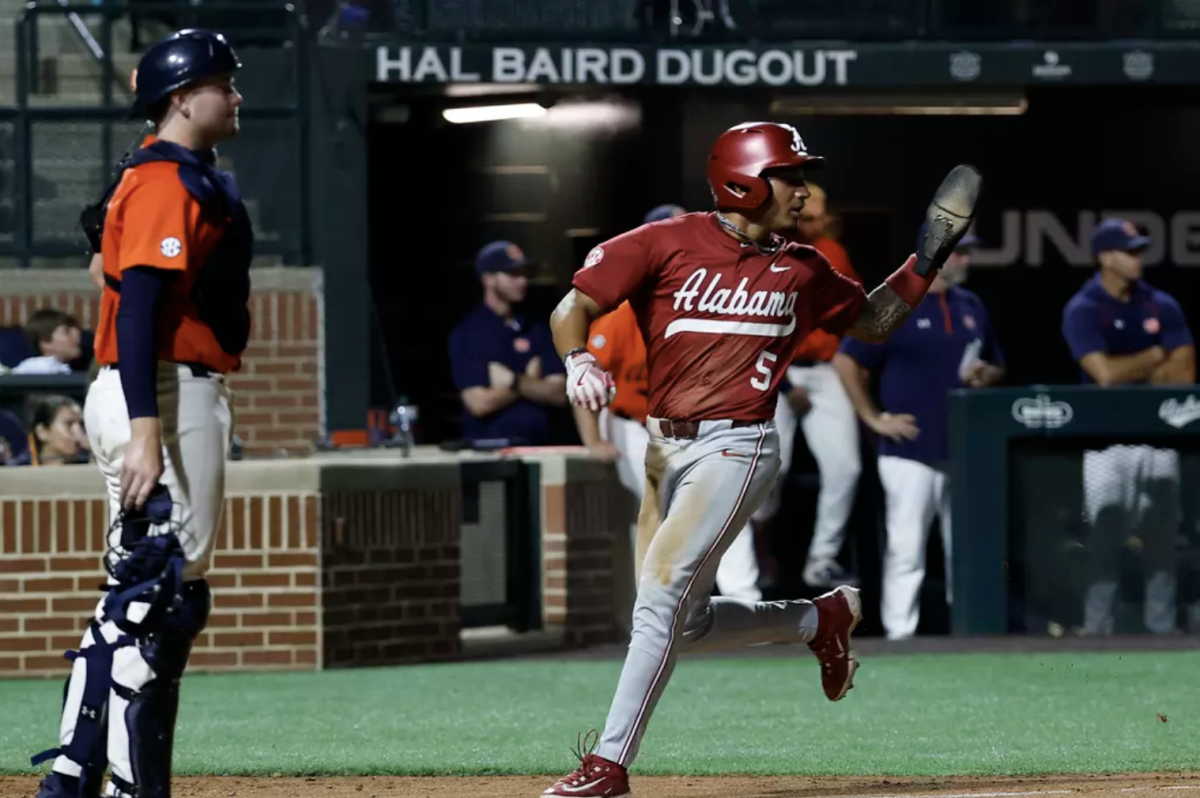

The growth Saban fostered while in command of Alabama football is massive and can be observed in a myriad of figures.

In terms of pure revenue, the time since Saban’s arrival has seen a 128% increase; in 2007, Alabama football brought in $57.4 million, and in 2022, it made $130.9 million.

This lucrative uptick in moneymaking trickled down to numerous parts of both the football program and UA athletics as a whole. Coaching salaries are a prime example of this. As of the 2023 season, Saban’s payrate sat at a comfortable $11.4 million, half a million more than second-place Dabo Swinney at Clemson and over $2 million more than anyone ranked eighth or below. For reference on the incredible growth this indicates, the 10-coach staff in 2007 made a combined $7.3 million, of which Saban was paid $4 million.

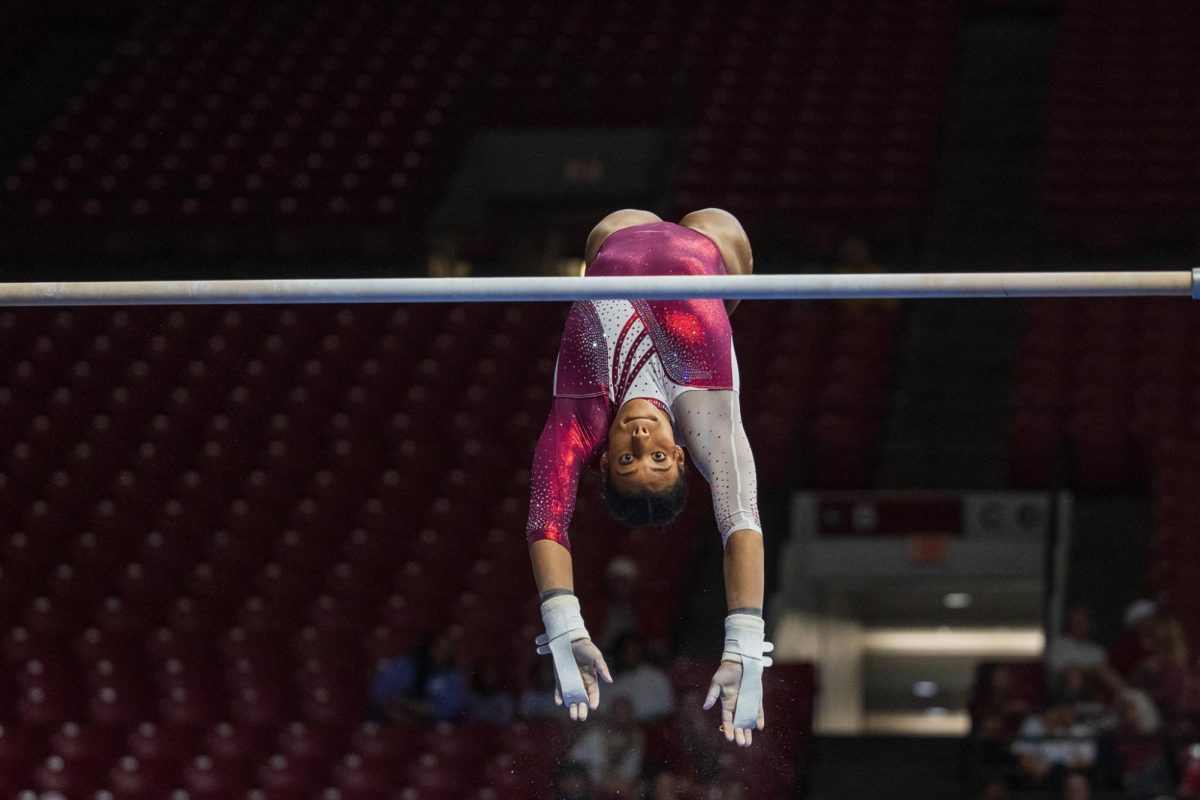

For Alabama’s athletics outside of football, the economic ballooning has been similarly potent. In 2007, the school brought in approximately $87.6 million from sports, with $17.7 from things like NCAA distribution, media rights and postseason activity; $22.7 million from ticket sales; $2.5 million from sponsorships and advertising; and $27 million from donors. In 2022, the total had shot up almost 150% to $214.4 million, and each of those subcategories doubled or nearly doubled.

The University

Alabama, the University, has been on its own conquest of expansion. Just looking at the surface level, enrollment has seen massive growth. Since Saban’s first season in 2007, the number of students has leapt from 25,580 to 38,645, a roughly 13,000-student increase in 15 years. Prior to 2007, it had taken the University 41 years — enrollment was approximately 1,900 in 1965 — to hit such a mark.

It would be a disservice to the hard-earned independent growth of the UA institution to say that it owes Nick Saban all its recent success. The school would likewise be imprudent, however, if it didn’t give him massive thanks.

After the retirement bombshell, freshman finance major Brogan Barnum revealed that Saban and Alabama football played a role in his choice of college.

“I’m a huge football fan, I just never had a team,” Barnum said. “Part of the reason was the football culture.”

The voracious and borderline religious love for the sport in Tuscaloosa proves that football culture was a reason for many. Even for those who didn’t blindly choose matriculation at Alabama because of devotion to the gridiron, the Saban-led success more than likely played some role.

The school’s relentless strategy of wooing strong students, especially out-of-state ones, with lustrous culture and generous financial aid has been heftily bolstered by the football program’s constant presence on the national stage.

It’s difficult to quantify Saban’s impact on the university’s growth, whether financial or demographic. What’s undeniable is that this impact exists, and exists prominently; as then-Chancellor Robert E. Witt said back in 2013, “Nick Saban is the best financial investment this University has ever made.”

The city

In a 2022 Crimson White piece describing the economic impact Saban had on Tuscaloosa as a city, staff reporter Mathey Gibson took the focus to a granular, structural level. A train of logic was put forth; it began with the football team’s driving of revenue and followed it up through campuswide upgrades, heightened attractiveness and a subsequent enrollment boost.

“The more enrollment climbs, the more needs the city of Tuscaloosa can fulfill,” Gibson wrote. “The more needs it can fulfill, the more business it can bring in. The more business it can bring in? You get the picture.”

Simply put, football is an integral part of the local economy. Tourism revenue for the city was a whopping $895 million in 2022, with each game day weekend generating somewhere between $20 million and $25 million. More than 4,000 hotel rooms provided more than $100 million in lodging.

The football scene is so ludicrous and lucrative that it plays a legitimate factor in various Tuscaloosa business operations.

In the words of Tiffany Lewis, manager of the Publix on the Strip as of September 2023, “Football season absolutely catapults us to another level as far as an increase in sales.” This boost in productivity via families coming for the games and staying through Sunday is so strong that, according to Lewis, it results in an extra $100,000 to $150,000 per weekend.

Daniel Shannahan, who has worked and been general manager in multiple Tuscaloosa bars, attested to football weekends being something of a livelihood.

“In some places where I’ve worked, you could pay your rent, your insurance, everything else on seven weekends, 14 days,” Shannahan said.

Beyond the local business side of things, Saban has gone on the offensive. Nick’s Kids, the charity foundation founded by him and Terry Saban, has had an extensive impact on the city. It has raised over $11 million for numerous causes and organizations. It has worked in schools, producing career tech classrooms for the Tuscaloosa County Juvenile Detention Center and the playground at the Alberta School of Performing Arts.

The foundation has also financed renovations at the Brewer Porch Children’s Center and built 19 Habitat for Humanity homes, 18 for national championships and one for an SEC title.

All of Saban’s contributions, whether direct or indirect, have catalyzed the continued evolution of Tuscaloosa as a perpetually amped-up college town and one of the biggest fall weekend tourist destinations of the South. Immense credit for the city’s and school’s economic growth goes to football, and immense — nay, inestimable — credit for football’s success goes to Saban.

More than just a coach, more than just a college football icon, Nick Saban has been a transformative economic force. He didn’t just leave sustained on-field dominance in his wake, but a program, college and city he helped put on a path of prosperity with no end in sight.