Since she was young, Leah Myers, a communications specialist for the College of Communication and Information Sciences, has been known as her family’s “record keeper”; preserving memories has been integral to her identity.

“I would keep everything,” Myers said. “Things that people would not really care about, not really want, I kept because it was important to me … because I think eventually people will want it again.”

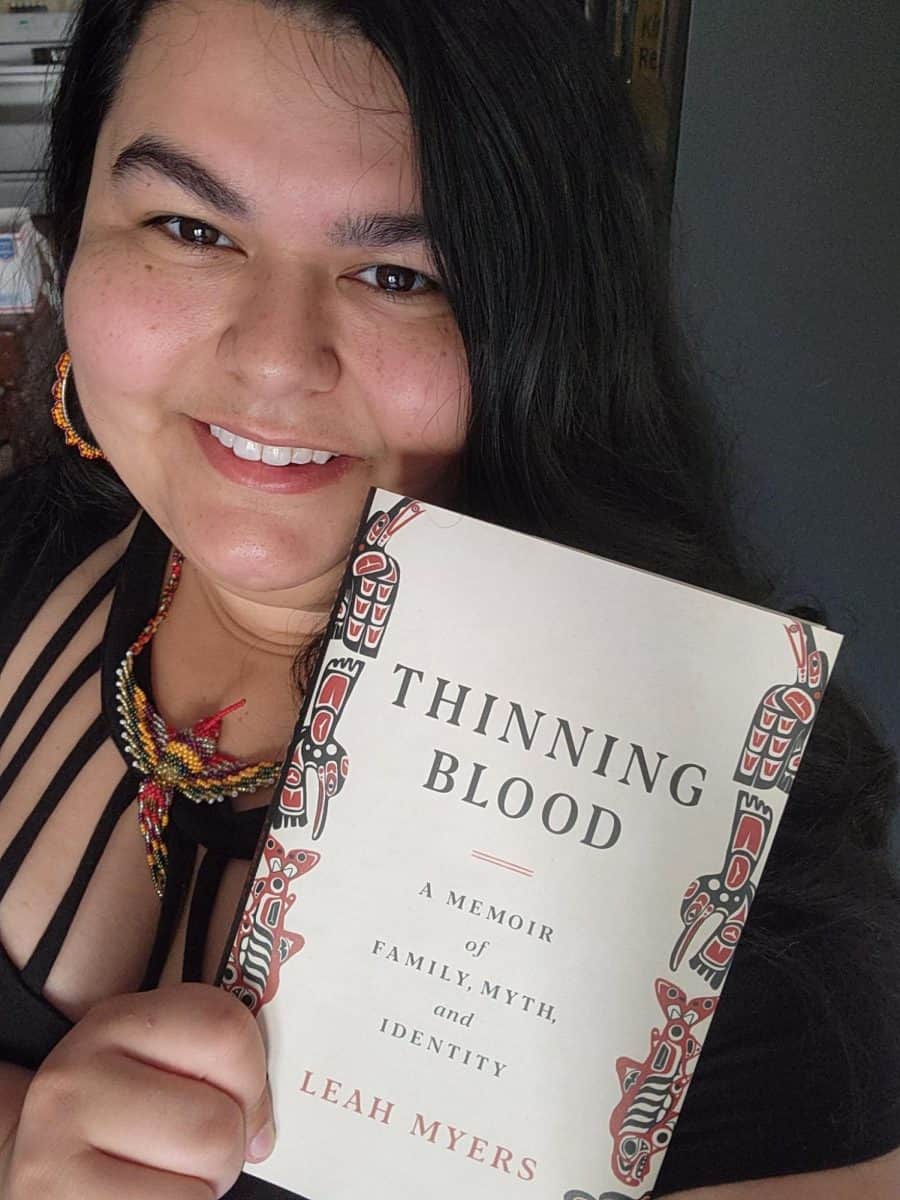

Her passion for preservation evolved into her debut novel, “Thinning Blood: A Memoir of Family, Myth, and Identity,” where Myers weaves folklore, heritage and history into a record of four generations of Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe women: her great-grandmother, Lillian; her grandmother, Vivian; her mother, Kristy; and her.

Split into four sections named after each woman’s totem or spirit animal, invoking the tradition of totem pole storytelling, Myers excavates the stories of her bloodline. Strict blood quantum laws, which dictate what quantity of “tribal blood” a person must have to be considered a tribal member, may make Myers the last in her line since her tribe’s blood quantum is one-eighth.

“The idea of ‘Thinning Blood’ is that I am one-eighth; so even if I had children unless they were with a tribal member — and I am from a very small tribe — they would not be considered native,” Myers said. “They would be considered a descendant.”

She said this would mean they would get fewer benefits and wouldn’t be able to have a voice within tribal politics.

Grappling with the weight of this truth has been an arduous journey for Myers.

She said she’s never wanted to be a mother, so blood quantum didn’t affect her as much as it would someone interested in starting a family. However, during her original research into tribal enrollment numbers in 2019, she was confronted with how this law could effectively wipe her tribe out after discovering that 297 of the 542 total members were one-eighth.

“I knew that this would be an eventuality,” Myers said. “I didn’t know that it was so close.”

She said she was devastated. She couldn’t stop thinking about the numbers for days, and it made her realize that her book wasn’t only about her and her family but her tribe and culture. She wanted to create something tangible, a memory for when the tribe would eventually be gone.

“My family history is shrouded enough, lost enough, that it is myth itself and blends easily with the legends of my people to create a seamless new record for the world,” Myers wrote in her book’s introduction. “I don’t want other Native Americans to go without, like my family has for so long. I want to give my generation a voice.”

Myers grew up not knowing her family’s stories, so along with the extensive research she did into broader Native American history, Native American and U.S. government relations, Pacific Northwestern mythology, and more for the book, she spent time interviewing family members, tribal members and cultural coordinators about their stories.

She said she’d ask the same questions to different people and parse through their accounts for the facts or to get to a point where she could at least say, “This is what we believe to be.” However, she wasn’t just interested in the facts; she also wanted to hold on to the myths.

“I think that myths are important in history, especially cultural history and tribal history,” she said.

She said sometimes mythmaking and family stories felt similar, like stories about her great-grandmother, who died when Myers’ mother was a toddler.

“Every story I know about her, there’s only a few, and they feel like myths because they are told the same way over and over with the same beats, and it feels like a mythology because it’s this person that has become a symbol of themselves,” she said.

She said she hopes her book can inspire people to think about their heritage more and start to pay attention to their family stories while there are still family members around to tell them.

“People don’t intentionally want to forget, but they think that the sources for those [stories] will always be around,” Myers said. “I hope that this sort of reminds people that that’s not always the case. You have to tell people your stories so that they know them.”

However, while the memoir is about preserving these myths and histories and creating something tangible, Myers also wanted to educate others on what history got wrong or omitted.

In 2019, when she wrote an essay about her heritage in her first Master of Fine Arts nonfiction writing class at the University of New Orleans, she discovered that she enjoyed writing about her culture and could educate people on things she thought were common knowledge while doing it.

She began working on a collection of essays that, three-quarters of the way through writing, turned into “Thinning Blood.” She started with the “big ideas” because, to her, when you start writing in any genre, you start with the concepts that mean the most to you or evoke the most emotion.

For Myers, that was a passive outrage at the things that had happened in Indigenous history that “were never fixed, never addressed, never even talked about.” This evolved into an exploration of her personal history, and the complex topics she didn’t know if she’d be able to write about, for fear that saying them would mean they were true. One of those fears was that she wasn’t Native enough because of stereotypes she’d harbored about how she should act.

“Like if I don’t understand how to create beadwork on my first try, that means I’m not Native enough, which is so silly to say out loud, but that’s how subconsciously I thought of it,” Myers said.

She said writing those parts and going through the journey of unlearning those beliefs was the most challenging part of the book.

“It’s something that I think a lot of people experience that nobody really wants to touch on,” Myers said. “We never want to admit that we think that way about ourselves.”

At first, she tried to “write around it,” but she didn’t want to lie and avoiding it felt like a lie of omission. Her commitment to telling her truth and her MFA cohort motivated her to write those hard parts. After writing it, she realized how “silly it looked on the page,” even though it hurt to write it.

Since the book landed on shelves May 16, Myers has seen how what she’s written has affected those around her.

Kristy Myers, her mother, said she was proud when she first read Leah Myers’ book. She said reading her daughter’s perspective about their family and seeing their heritage through her daughter’s eyes was amazing.

“Some of it was hard to read as a mom. Some of it was difficult for me to see in writing, but it was also, at the same time, so poetic and so beautiful that by the end of the book, I was just in awe,” Kristy Myers said. “I mean, I know she’s my daughter, but I was in awe.”

The positive response to Myers’ book also extends outside of her family, with “Thinning Blood” being named a most anticipated book of 2023 by the literary magazine The Million. And being called a “slender and poetic” book that is “also wide-ranging, moving with ease from memoir to Native history to myth and back again, yielding a blend that transcends genre” by Maud Newton from the New York Times.

She’s also received positive feedback from people online who have tagged her in things or said they felt represented by her work. She said that has felt amazing.

“I never would have expected that because when you write a book for yourself, you don’t really think about how other people in the same situation might also need it,” Leah Myers said. “So, it’s been really touching to see all of that and to see it out on shelves.”