Many people questioned whether Governor Robert Bentley, a retired dermatologist and University of Alabama graduate, could do the job. After a year in office, leaders across Alabama are beginning to evaluate his decisions and early legacy.

“He has been put in a very difficult position to represent all the people of this state while having to deal with natural disasters and other things,” said Republican state representative John Merrill of Tuscaloosa. “I think that one of the things that’s very clear is that this is one of the most difficult times to be governor in our state’s history.”

Stephen Borrelli, a professor of political science at Alabama, believes that Bentley has made his share of rookie mistakes, but also believes that he has surprised many.

“He’s managed to survive a tumultuous year in state politics that might have overwhelmed a lesser governor,” Borrelli said.

Early struggles

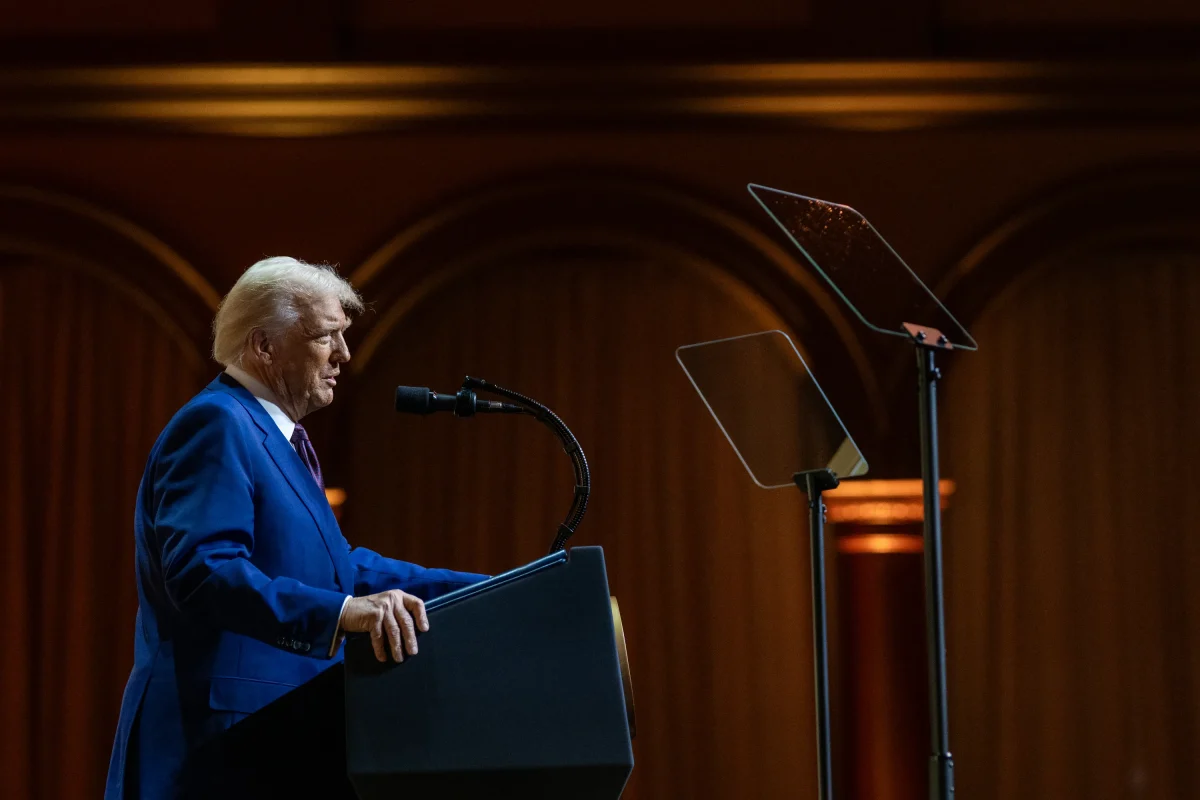

Bentley had a rough start in office. On the day of his inauguration, he gave an address to the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church in Montgomery. It was intended to serve as a speech in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, as King once spoke at the historic church. It became, however, an early obstacle and a point of religious outrage.

”If we don’t have the same daddy, we’re not brothers and sisters,” Bentley said. “So, anybody here today who has not accepted Jesus Christ as their savior, I’m telling you, you’re not my brother and you’re not my sister, and I want to be your brother.”

Those remarks caused outrage in the state and raised questions about whether non-Christians could expect fair treatment from the governor.

Bentley soon apologized for his comments and, according to the Birmingham Times, said, “If you’re not a person who can say you are sorry, you are not a very good leader.”

Response to Disaster

April 27 was Bentley’s hundredth day in office. On that day, 62 tornadoes touched down in Alabama in a historical severe-weather outbreak that killed more than 250 people.

Bentley sprung into action and was instrumental in the response, refusing to allow FEMA to take control.

“I think many Alabamians appreciated that,” said Richard Fording, the chair of UA’s political science department. “Most everyone agrees that his post-tornado leadership has been exemplary. His coordination with Federal and local officials has shown that there would be none of the finger-pointing, bureaucratic SNAFUS and partisan conflict that marred the government response to Katrina in Louisiana.”

Economic impact

Besides the natural disasters, Bentley also had to contend with a poor business climate and stagnating economy. Sworn in with a 9.3 percent unemployment rate, Bentley has seen it fall to 8.1 percent, 0.2 percent below the national average.

Bill Poole, a republican representative from Tuscaloosa, said he is unsure whether Bentley or federal initiatives deserve the credit.

“I certainly hope [the recovery can be credited to Bentley], but what drives employment numbers is always open to debate,” Poole said. “We are gaining steam and heading in the right direction.”

Merrill agreed, and said the facts of the state economy spoke for themselves.

“Our income taxes are up. Our sales taxes are up,” Merrill said. “I can’t tell you that those facts are all related to the governor’s economic plan, but those are the facts. The proof is in the pudding.”

Borrelli was not as convinced, however.

“I think Alabama was not quite as devastated by the Great Recession to begin with and began to move out of recession more quickly for reasons that don’t directly relate to the governor’s actions,” Borelli contended.

Controversial Immigration Law

The governor’s most controversial decision is also the one that has brought him the most attention: The state’s tough new immigration law, House Bill 56.

The bill was swiftly passed by the Republican-dominated state legislature and signed into law by Gov. Bentley in June. It was met with intense, immediate opposition.

“I find House Bill 56 to be a naked, racist political ploy and one that will cost Alabama taxpayers millions to defend in court,” said Michael Fitzmorris, a junior who serves as the vice president of the Alabama College Democrats. “Alabama is less than 50 years removed from the civil rights era and would do well to avoid embracing costly, hateful mistakes of the past.”

The law requires proof of citizenship when renewing or applying for a driver’s license and requires all employers to use the ALverify system, which was developed by the Center for Advanced Public Safety at the University of Alabama and gives employers the ability to quickly check the citizenship of its workers against various state databases.

The law makes it illegal to knowingly hire an illegal immigrant and mandates all public schools to check the immigration status of all of its students. It also criminalizes many activities labeled as aiding an alien, such as giving them a ride.

The Department of Justice quickly filed a lawsuit in the Northern District of Alabama in response to the law. In a statement released to the media, the DoJ expressed its reasoning: “Various provisions of H.B. 56 conflict with federal immigration law and undermine the federal government’s careful balance of immigration enforcement priorities and objectives.”

Borrelli said he thinks that Bentley overstepped his bounds with the law.

“The governor had no idea what a public relations disaster the bill would be in the national media, and it would play into the historical depiction of Alabama as unwelcoming and hostile to minorities.”

Merrill, in contrast, voted for the law and said all it did was require that all people be treated equally.

“We know that there are people who need jobs, and we also know that there are companies that want to hire people,” Merrill said. “At the same time, we know that some people would rather stay at home and drink Coca Cola than work.”

Poole also agreed that Bentley was justified in acting on the immigration issue.

“Unfortunately, we have a real issue in immigration,” Poole said. “The governor did what he thought was right, and I agreed with him.”