Going to college may cut a young person’s risk of attempting suicide in half, experts say.

According to an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2006, the school suicide rate, estimated to be about 7.5 per 100,000 students, is about half the rate seen in nonstudents of the same age.

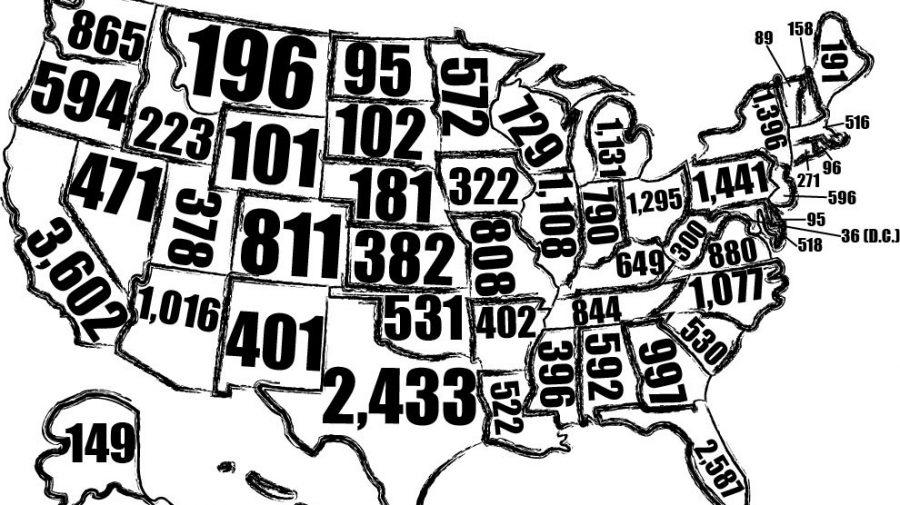

The article states that an estimated 1,100 suicides and 24,000 attempts occur in college students ages 18 to 24.

Lee Keyes, psychologist and executive director of the University of Alabama Counseling Center, said there are several theories to account for this data.

“If you think about who is in college, they’re people who are forward thinkers and planning for their futures,” Keyes said. “Folks who may not have hopes or plans about the future may be more depressed. Also, people who are able to go to college are often economically better off or have more resources.”

Despite a lower national trend among college students, the University’s suicide rate since December 2010 is approximately double the estimated national rate of 7.5 per 100,000.

According to the American Foundation of Suicide Prevention, suicide is the third leading cause of death among American 15-24 year olds – regardless of education.

Larry Deavers, executive director of Tuscaloosa’s Family Counseling Service, echoed Keyes’ idea of forward thinking when asked why young people commit suicide. He said young people’s limited life experiences might factor into the decision to take one’s life.

“They may not have a real broad worldview of problem solving or the forward thinking that this problem is temporary, that it seems overwhelming right now, but ‘I can eventually get through,’” Deavers said. “Older adolescents seem to think more in terms of absolute. When they face the situation, sometimes they tend to make it seem more awful than it is because it seems so intense or so bad. They have a hard time thinking through what it will be like on the other side.”

Despite these statistics, Keyes said people should remember that suicide is preventable.

He urges friends and family to watch for red flags like pessimism, withdrawal from normal social activities, increased sleep habits, increased substance abuse or verbal indications of a desire to harm oneself, and to take action immediately.

“When someone accesses help, the suicidal impulse goes away fairly rapidly,” he said. “Be a good friend, talk with the person and express care and concern. Stay with them, and tell someone who is in a position to help.”

Keyes suggests going to religious leaders, family members, the police or taking advantage of on-campus resources like the Student Health Center or Counseling Center.

“We have 22 people on staff – psychologists, counselors, social workers and psychiatrists,” he said. “Altogether, we have well over 100 years of combined experience in mental health in a variety of settings.”

On-campus residents can also look to residence advisors for help, as they are trained extensively in August and will attend suicide awareness training this month. Some students may find a person closer to their age more approachable.

“We emphasize with our staff to go with the student to the counseling center or help them make that appointment – to assist them with that process and help them get over the initial hurdle of seeking help,” said Amanda Wallace, assistant director of Housing and Residential Communities.

“It makes a difference if someone is willing to go with them to get help, instead of telling them what they need to do,” Deavers said. “It makes them more comfortable and more willing to seek help for themselves.”

For more information about suicide prevention, go to afsp.org, contact the University’s Counseling Center at (205) 348-3863, or, if you are in crisis, call 1-800-272-TALK.