As Alabama strength coach Scott Cochran comes across the screen at Bryant-Denny Stadium, the crowd erupts and Alabama fans across the stadium put up four fingers to signal the beginning of the fourth quarter. The Crimson Tide knows it is time to shine as it looks to carry on the tradition of being the best fourth-quarter team in football.

However, there is another team on the field who also is well prepared for the fourth quarter. They too are donned in crimson and provide important assistance to every Tide victory.

The University of Alabama Athletic Training Program provides healthcare across many of the University’s athletic programs, including in-game assistance to players in need.

“We are, in a sense, the first responders on the field,” said Dr. Deidre Leaver-Dunn, associate professor of health science and director of athletic training education at the University of Alabama. “If an athlete goes down on the field, an athletic trainer is immediately by the athlete’s side to assess the injury.”

Many of these trainers learn the ropes through he Athletic Training Education Program (ATEP), which provides exposure to students by placing them in clinics and athletic programs both at Alabama and in high schools around Tuscaloosa. Upon completion of the program, each student must pass the Board of Certification exam in order to be fully certified as an athletic trainer in Alabama.

More than meets the eye

Many in the crowd assume that athletic trainers are no more than water-boys. However, being an athletic trainer involves much more than simply keeping the players hydrated.

“That is far from who we are,” senior Jacob Bell said.

Bell, a 3rd Year Athletic Training Education Program student echoes the sentiment of many in a profession that often gets overlooked for its importance to the world of sports.

“Injuries happen all the time in sports, and as allied health professionals we are called on as part of the recovery and rehabilitation process,” he said.

The training program prepares its students not only for injuries that occur at Alabama sporting events, but also for future allied healthcare professions such as professional sports.

Bell said his exposure while working with the Tide football team helped him receive an internship with the Detroit Lions during the 2011 NFL preseason.

“My experiences and training in the program at UA really translated in my ability to serve the athletes in Detroit at a quality level of service,” Bell said. “ATEP has taught me to be a hard worker and I’ve gained a lot of experience in the program that will help me in my career exponentially.”

Dealing with disaster

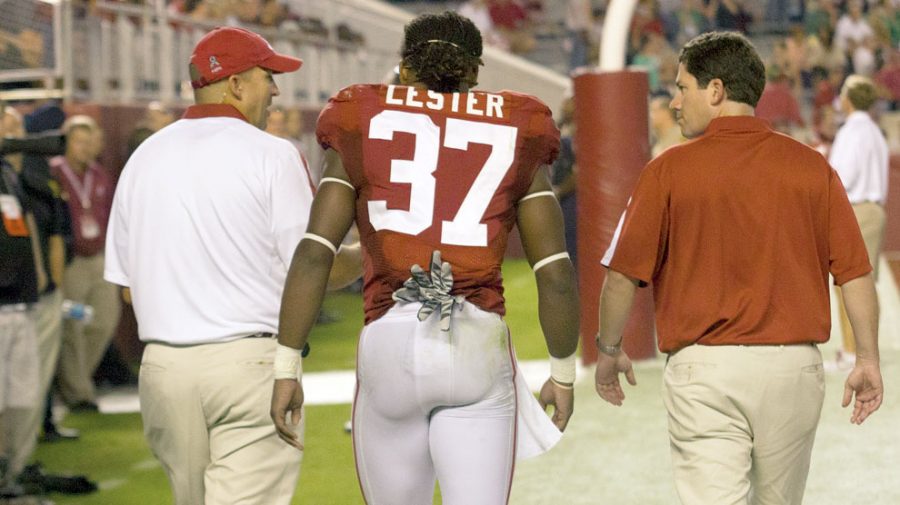

Often times, the athletic trainers have to deal with gruesome on-field injuries with poise.

One of the most infamous injuries in the history of Alabama Athletics occurred Oct. 1, 2005. During the game against Florida, talented wide receiver Tyrone Prothro, while attempting to make a catch, landed awkwardly in the end zone and snapped his tibia and fibula – the two major bones in his leg. Upon seeing the severity of pain he was in, teammate Keith Brown waved the athletic training staff over.

Athletic trainer Justin Skidmore said not only does the staff have to handle situations on the field, but they also assist in the rehabilitation process.

“We [athletic trainers] are present on the field following an injury like Prothro’s,” Skidmore said. “But what people don’t see is that we are present in the rehabilitation process in the days, weeks, and months that follow an on-field injury.”

Another common type of injury that athletic trainers focus on in depth is neck-related injuries. These injuries are often life threating and require instant care from athletic trainers.

Rutgers University football player Eric LeGrand is a prime example of why having an athletic trainer present on the sideline is extremely vital to the wellbeing of the players. In 2010 the former Scarlet Knights defensive tackle attempted to make a tackle on the kickoff and in the process collided with an opposing player, injuring his neck.

“In a situation like Eric LeGrand’s, all of the training in the classroom comes into play,” Leaver-Dunn said. “We immediately stabilize, in this case, the neck, and prepare the player for further medical attention whether it is in the locker room or at the hospital.”

LeGrand ended up becoming paralyzed from the neck down. But many, including LeGrand, have said if it had not been for the immediate response of the athletic trainers and how they handled his injury on the field, he might have not made it to the stretcher.

“We teach our students early on how to approach cervical spine injuries,” Leaver-Dunn said. “In some cases, it can be the difference between life and death.”

A humble, helping-hand

As the team cheers the return of an injured player back to the field, often times the athletic trainers are left to stand in the shadows. However, Skidmore said the satisfaction of doing his job is well worth the lack of recognition.

“Being an athletic trainer, you have to, in a sense, have a servant’s hand,” Skidmore said. “It’s not about the glitz and the glamour of the sport. You’re satisfied by getting the athlete back on the field and knowing you helped him or her get back out there. That is why I love doing what I do, for that satisfaction alone.”