Tuscaloosa struggles over future of affordable housing

October 15, 2020

The Tuscaloosa City Council voted unanimously to extend an ordinance that placed a moratorium on building permits and land development permits for multi-family, student mega-complex developments.

Student mega complexes are considered apartment buildings of 200 bedrooms or more, with units that typically contain four or five bedrooms each.

The decision was but one in a series of ordinances passed recently by the city council that aim to slow the number of new bedrooms being built in the University Residential District and curb the number of new large-scale student housing projects.

“(My) district has been changing remarkably, and gotten ahead of itself in terms of housing,” said Tuscaloosa Councilman Lee Busby, whose District 4 includes the University Residential District.

Busby said the aim of the moratorium is to let the demand for housing in his district catch up.

Tuscaloosa Mayor Walt Maddox said the proliferation of student mega complexes has created a surplus of beds in Tuscaloosa.

“Since 2011, the University of Alabama has grown by 7,871 students, while in the same time, over 14,000 new apartment bedrooms have been added,” Maddox said in a June press release.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Tuscaloosa has an overall 4% rental vacancy rate.

But that number is not reflective of the vacancy rates of the larger, multi-family, student-oriented housing in the city, which have much greater vacancy rates.

The HUD study showed that multi-family developments with five or more bedrooms had a vacancy rate of 40%, and multi-family units with between two and four bedrooms had a vacancy rate of 16%.

“With land prices so high, it’s hard not to build vertical,” Maddox said. “When you purchase the property, it makes more financial sense for the landowner to be 50% full with a student complex than to be 100% full with traditional housing.”

According to a five-year affordable housing study commissioned as a part of the city’s Framework initiative, the demand for housing will eventually meet the supply. But with the majority of available units being three, four and five bedrooms, the study indicated that the most widely available type of housing will not meet the price point or style of unit that the majority of potential renters in Tuscaloosa will be looking for.

The study showed that the average rent for units between three and five bedrooms ranges between $1,000 and $2,605. For a one-bedroom apartment, the average rent was $779.

Nearly 60% of renters in Tuscaloosa are cost-burdened, meaning that the cost of their rent is 30% or more of their overall household income.

For the estimated 6,600 retail workers in Tuscaloosa, who make an average annual income of $26,150, the maximum affordable rent is $654.

“The overbuilding of student apartments has not translated to lower prices for students, nor has it translated into any type of affordable housing,” Maddox said. “Clearly, we have reached that breaking point and we have to walk away.”

Maddox said he believes the city should move away from mega-complexes and focus on the development of more traditional housing, like plexes and townhouses.

Plexes are properties that have two, three, or four, family homes, which typically have shared walls, within one building.

The city council also voted 5-2 in favor of an amendment to the city’s zoning ordinance that would bar property developers from building four- and five-bedroom units in future multi-family and student mega complex apartments.

The moratorium on four- and five-bedroom spaces applies to student mega complexes, but not to duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes, townhouses and row houses.

Michael Cartee, a real estate developer from Chicago and a Tuscaloosa lawyer who represented Core Spaces, said the exception for plexes is “fundamentally unfair,” and that plexes cause horizontal sprawl and blight.

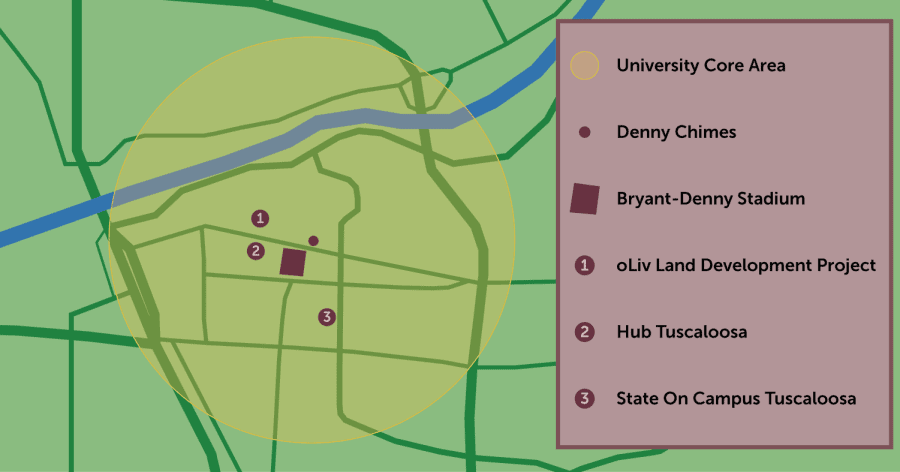

Core Spaces developed both The Hub and The State student apartments in Tuscaloosa and

has plans to build a student mega complex called oLiv on 319 Grace St., where the Pride Court apartment complex is currently located.

Tuscaloosa attorney Bryan Winter, who also represented Core Spaces, said the city currently incentivizes four and five bedrooms for plexes in the way that it handles service fees, which land development projects pay to the city to cover the impact that they have on city infrastructure.

Service fees are charged to housing developments by the number of units, rather than by the number of bedrooms and bathrooms.

Winter also said he believes the moratorium on multi-family and student mega complexes is “pushing back on outside economic investment and job creation.”

For the oLiv development in particular, Cartee said that the decisions made by the city to limit the project would cut off a $41.7 million investment and prevent 400 or more new jobs.

Robert McLeod, professor of finance at The University of Alabama’s Culverhouse College of Business, said the economic impact of large-scale land development projects like student mega complexes “make a very large contribution to both city and school taxes.”

“If we unduly restrict these kinds of developments, it’s going to hurt Tuscaloosa’s economy,” McLeod said.

After studying 2019 economic data with Samuel Addy, head of the Culverhouse Center for Business and Economic Research, McLeod said they found that for every dollar in construction spending, there is a positive economic impact of $2.40, and large housing development projects had an over $500 million impact on Tuscaloosa’s economy that same year.

“All of the building-skill trades are going to benefit from advancing these projects,” said McLeod. “The impact is something that is going to benefit local contractors, minority contractors, and all of the skilled trades are going to be impacted positively by these types of developments.”

McLeod also said large-scale developments like mega complexes have a positive economic impact by paying hundreds of thousands of dollars in service fees, building permits and business licenses to the city.

“Another area that we need to look at is cost savings,” McLeod said. “These developments have their own garbage pickup, so there’s no need to drain city services to pick up trash. It has the benefit of a cleaner, neater area, and it cuts down on some of the city services costs.”

Maddox said he would prefer to see more traditional housing and commercial properties in the place of mega complexes.

52% of Tuscaloosa’s revenue comes from sales tax, with 3% coming from rental taxes.

“Every time we build a new mega apartment, we take away the possibility of that being redeveloped as a commercial opportunity,” Maddox said. “That commercial opportunity is what generates revenue for schools, streets, the police department and other services.”

Both Tuscaloosa City Council and Maddox expressed major concerns about the pressure that student mega developments are putting on the city’s infrastructure during the Sept. 22 council meeting.

Maddox said while student mega complexes “may be of benefit to certain areas of the city,” he also believes they cause student-oriented housing outside of the University’s core area to struggle with vacancy and crime issues.

A secondary issue, Maddox said, is that mega complexes cause infrastructure issues within the University’s core area.

Student mega complexes typically have amenities such as underground parking, clubhouses, pools and gyms, which can put additional strain on city infrastructure.

“Mega developments cause a high concentration of people,” Busby said. “That means roads wear out faster, and sewer pipes are falling apart underneath them, so we have to fix the infrastructure to accommodate them.”

Busby said he believes the moratorium should extend to plexes, and he has asked his staff to draft a version of the moratorium that would include plexes.

At the Oct. 6 city council meeting, Tuscaloosa City Council voted in favor of introducing a new set of amendments to the city zoning text that would introduce new height and density caps for new building developments in the city.

The public hearing and vote on the amendments is scheduled for Nov. 3, the same date as the U.S. presidential election.

Cartee said city council should move the date of the vote due to concerns about a poorly attended meeting with a lack of “sufficient public input.”