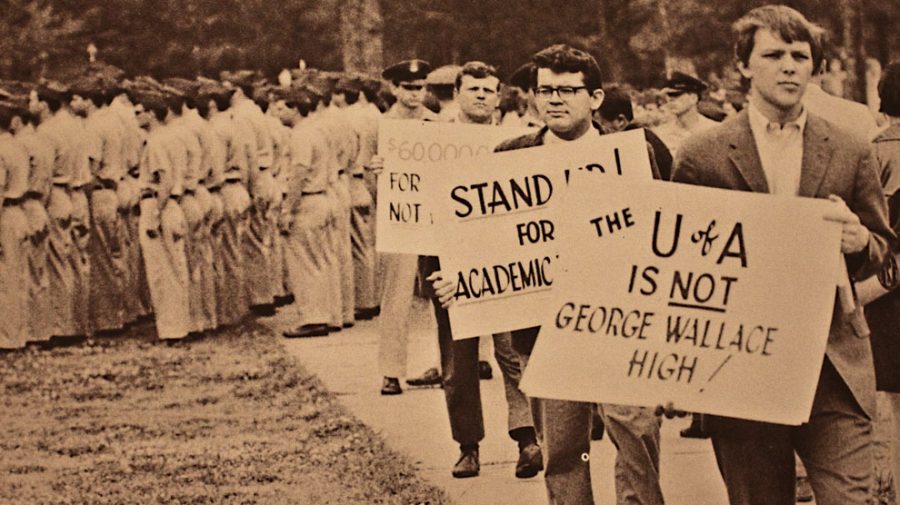

Along with sex, drugs and rock and roll, tensions roiled in Tuscaloosa in the 1960s and early 70s. Beneath an apathetic veneer laid pockets of political unrest.

The anti-war movement was the unpopular elephant in the room that fueled police brutality towards students and erupted on campus as explosive dynamite. Former student activists served as panelists reliving the events of their youth in the Days of Rage Conference at the Capstone Hotel Friday.

Roundtable participants included: Tom Ashby, Eugenia Twitty Croshack, Jack Drake, Billy Field, Wayne Greenhaw and Carol Ann Self. Each contributed his or her personal recollections of a different era at the University.

Greenhaw, a former reporter for the Montgomery Advertiser, recalled a time when he personally encountered violence with the police on campus.

“A city bus pulled up in front of the Union building, and city policemen filed off with black tape over the numbers on their badges,” Greenhaw said. “They carried no side arms, and they all had billy clubs.”

Greenhaw recognized that this was news, and so he said he stepped off the curb to call his editor from a telephone booth.

“A policeman grabbed me and pushed me back,” Greenhaw said. “I heard a cry of anguish as they pulled a girl by the hair out in the middle of the street. Then I took off running to the phone booth to call my editor.”

That was when Greenhaw said he saw a policeman coming with a billy club toward his head.

“It scared me to death,” he said. “I took off running again, and the kids at the DKE house pulled me in and got me a phone to call the newspaper. My editor didn’t believe me at first, so I held the phone out the window so that he could hear all the screaming.”

Field, who came to the University in 1967, also tells of how the police behaved violently toward students.

“One night, we gathered at Quick Snack where the Sigma Nu house is now, and we were planning a peaceful march to the president’s mansion,” Field said. “We got to the Union building, and police officers with Confederate flags on their shoulders ordered us to ‘disperse.’”

When the University attorney leading the march tried to explain that the march was peaceful and constitutional, “the cop reared back and hit the guy over the head,” Field said.

“The guy crumpled to the ground, and we all ran,” Field said. “I climbed to the top of a column and watched them beating kids like watermelons. ‘Thud, thud, thud.’”

Keynote speaker Earl Tilford believed that the police brutality was caused in part by the city police feeling undermined by the University police department.

Tilford said Tuscaloosa was also the Ku Klux Klan national headquarters, which helped stir up further political dissent. People could buy hunting licenses for black Americans and caricatures of Martin Luther King Jr. could be found in barbecue joints past 14th Street, Tilford said.

Former Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman, who was president of the Student Government Association during this time, remembers challenging University administration about playing “The Plague of Dixie” at football games.

“There were a number of us who felt that the song was an affront to African American students and that it wasn’t what we should be doing for successful integration,” Siegelman said.

Crosheck said she was involved in the first civil rights demonstration on campus.

“There were only two people,” Crosheck said. “After Martin Luther King had been assassinated in Memphis, an African American student and I walked around the quad together in memory. It was an awakening for me.”

Blacks and hippies were both stigmatized at the time. Ashby, a Vietnam vet, recalls returning from the war and recognizing the prejudices of society.

“Vietnam did not make me an activist, because I was an unwilling participant, but it did open my eyes to certain things,” Ashby said. “I fought beside men of all races and color didn’t matter because we had a common enemy.”

When Ashby wore his fatigues to a candlelight vigil, an Alabama linebacker came and stomped out the candles, staining his jacket with wax. He said he knew that the anti-war position was not a popular one, but he felt it was his responsibility to the country to make known what was happening in Vietnam.

Drake, a former rebel who was often known to be in the center of any protest, and Self, a self-proclaimed sorority girl turned radical, also had exciting stories to tell regarding this period in history.

“Having been a photographer for The Tuscaloosa News during those fateful days in May, I was interested to come back and see what people had to say 40 years later,” said Daniel Meissner, a UA journalism professor. “Some stories have probably been embellished over time, but those were heady days. It is instructive to see where we are and how those events shaped the University today. ”