The domes belonged to Alabama Insane Hospital, the first of its kind to be completed in the state of Alabama in 1859. When it finally opened in 1861, it was surrounded by acres of green farmland and people praised it for its then architecture. Patients were greeted by the same huge white dome that graces the building today.

Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, an activist since the 1830s, created the idea of the building becoming a part of the treatment, providing amenities and a good living situation for its patients. The hospital, eventually renamed Bryce Hospital, promised its patients running water, gas lighting and 70-degree air conditioning which was revolutionary for that time, as explained by Brad Cook, the current University of Alabama project manager in construction administration.

The Alabama Insane Hospital was founded on the belief that treating patients with dignity and respect, rather than like prisoners, was the ideal way to treat mental illness. Dr. Peter Bryce, the first superintendent of the hospital when it first opened, popularized the previously unheard of moral treatment theory.

“He revolutionized the industry,” Cook said. “He treated the mentally handicapped like people. He was kind of cutting edge for that movement.”

It wasn’t always that way though.

While the state of Alabama served as the pinnacle of mental health treatment for years, it eventually fell into disarray by the mid-20th century. With conditions the Montgomery Advertiser compared to Nazi concentration camps in the 1970s, Bryce Hospital fell from its glory, and abysmal conditions remained for some time. Over the following years, Bryce worked and was able to regain the top conditions it once boasted by reevaluating their original treatment plan.

The 326 acres of the original Alabama Insane Hospital were adjacent to the University, and both were two miles from the city of Tuscaloosa at the time built. Naturally, The University of Alabama and Bryce Hospital have been intertwined since the hospital’s opening, even with various patients of Bryce acknowledging the relationship, too. In the patient-run newspaper, The Meteor, similarities and differences between the institutions and their practices were pointed out and recorded.

“From the very first time the foundation of Bryce Hospital main building was laid, there has been a connection between The University of Alabama and what was then called Alabama Insane Hospital,” said Steve Davis, current Department of Mental Health Historian Steve Davis.

Davis said that the hospital superintendents and the University presidents shared a long history, and that when the Civil War ended, Bryce offered to let the University use parts of the vacant east wing of the hospital as classrooms. Then-University President Josiah Gorgas, along with his wife Amelia, actually lived with Peter Bryce and his wife Ellen at the hospital. Amelia Gayle Gorgas and Ellen Bryce became best friends, and so did their husbands, Davis said. J.T. Searcy, the second superintendent of the hospital, acted as the personal physician of Gorgas, in addition to the next president of the University. In fact, the University president’s home would typically get its food from produce grown at Bryce, which owned many acres of farmland.

With all of these connections, it’s no surprise that the University’s psychology department was associated with the hospital, and Davis said that most students completed their internships there. Dr. Ray Fowler, a psychology professor at the University, claimed the Wyatt v. Stickney case started in his living room. This case, filed in 1970, led to a great deal of progress after a 1999 settlement agreement was made to ensure that mental health standards were established.

“Enormously significant historical events may have very modest beginnings,” Paul Siegel wrote in his book “A Personal History of the Department of Psychology of the University of Alabama,” written in 1995. “Sometimes they are ‘accidentally’ determined. Something like that happened in the psychology department in the summer of 1970.”

Even today, the relationship with the two institutions continues, and the University officially bought the Old Bryce campus in 2010, something it’s talked about doing since 1969, Davis said.

“I’ve got a letter from 1977,” Davis said. “A newspaper article from 1977 that they used to bring out in management council and read and they’d say ‘yeah, that was in the Tuscaloosa News last week,’ and this was in 2007, and I’d say, ‘no, this was in the Tuscaloosa News in 1977.’”

Since then, the relationship has evolved over time.

“When they first started, it was a very close relationship, but they were obviously completely separate,” Davis said. “At this point in time, they’re totally integrated.”

The new Bryce campus was built with University funds under University leadership and is currently on the University’s campus. Davis said that the University pays for the maintenance and the hospital relies on the University for all of its auxiliary services.

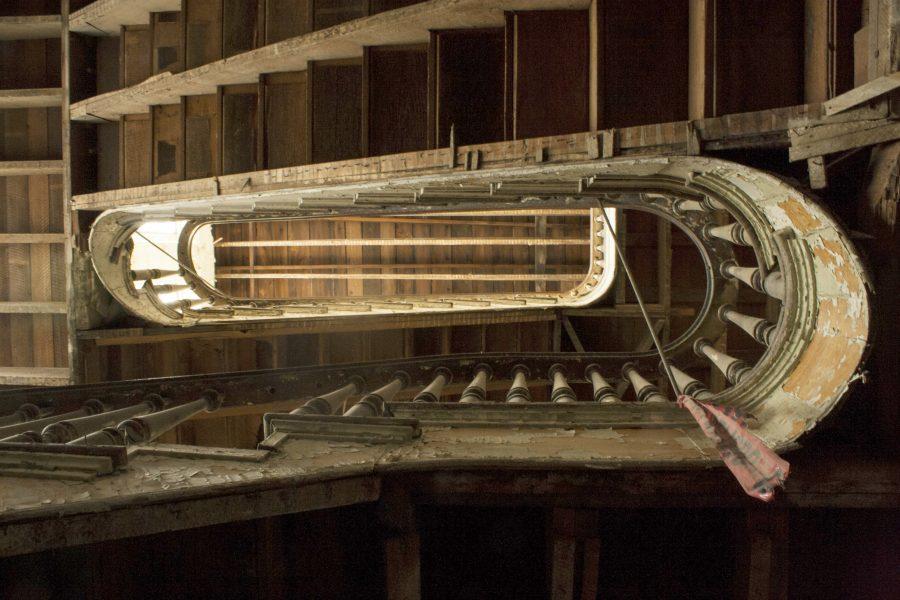

The treatment of mental illness at Bryce Hospital has come full circle over the past 150 years. The white dome outlasted all the changes, but the same can’t be said for other parts of the facility. Patients have recently been relocated. There used to be six wings of the facility, but now only two remain. A veil of dust covers every surface. Walls have been torn down, paint is chipping and dirt piles are in every corner. Vandalism dominates what walls are left, and the building is a shadow of what it once was.

Still, the heartbeat of the old facility can be felt. Murals and motifs that were hand-painted so many years ago can be seen under the peeling paint. Within the piles of dirt are old Christmas decorations, torn and forgotten. In the amusement hall, where patients used to have proms and performances, there remains a single, framed painting of birds flying over the ocean.

“In a perfect world, I wish that the original Kirkbride building could have been kept, but never in my wildest imagination did I believe that the University would’ve been able to renovate as much as they have,” Davis said. “So that has been a pleasant surprise.”

The University has made sure the legacy of Bryce stays alive. They’ve restored the grounds to how they were in the 19th and 20th centuries. They’ve put new fences around the cemeteries, and some say that the evolution of the relationship between Bryce Hospital and the University reflects the evolution of mental health treatment as a whole.

“I know it’s trite to say win-win,” Davis said. “I know everybody uses that, but it really is.”