Buzzfeed recently posted an article titled “20 Incredible Books From The Past Year You Need To Read Right Now,” featuring the longlist for the Baileys Women’s Prize For Fiction 2015. While the post is a cool way to get readers engaged in female writers, a promotion of the classical ones, the trailblazers, also seems pertinent.

Take Shirley Jackson – known almost universally to anyone who attended middle school for her short stories “The Lottery” and “The Possibility of Evil,” Jackson is considered a masterful writer even now, fifty years after her death. Her legacy as a mystery and horror writer is iconic and notably creative, but what often times is overlooked is the prevalence of faulted and yet resilient female leads.

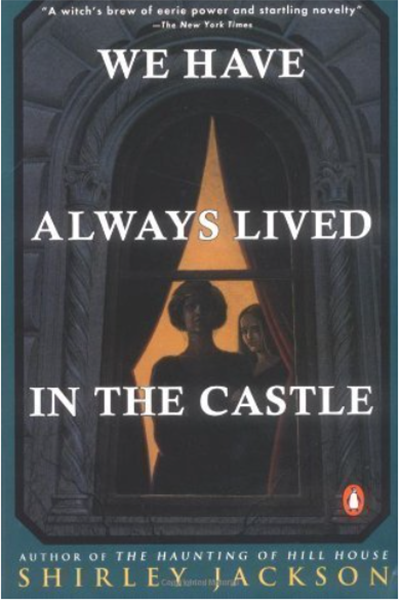

In “We Have Always Lived in the Castle,” Jackson reports the story of the remaining three Blackwoods – Mary Katherine, the 18-year old shut in; Julian, the invalid uncle; and Constance, debatably the a murderer and the reason the remaining Blackwoods are so few. The opening paragraph contains sentences like, “I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had,” and immediately invests the reader into the strange, detached world Jackson molds out of thin air.

The writing in the ten-chapter “We Have Always Lived in the Castle” is dramatic and poignant, and the closest connection would be to associate the piece to the stylings of the 2013 movie “Stoker.” But whereas “Stoker” was vague in a dissatisfying way and overtly sexual, “We Have Always Lived in the Castle” uses its protagonists’ naivety to build drama when an evil force in the way of a visitor appears.

Dark and brooding, Jackson’s novel is a classic horror, but moreover, it is a piece worthy of appreciation on the basis of its contrasting female leads Mary Katherine and Constance. Jackson’s works are definitely worth a read – especially those short stories one can read in one sitting between pouring over textbooks. For a more involved analysis of Jackson’s work, “We Have Always Lived in the Castle” is a must.