On an otherwise quiet Sunday morning, 600 people began lining up at Brown’s Chapel in Selma, Alabama, to start the 44-mile march to Montgomery. Some packed bags, while others viewed the march as merely a symbol and wore their Sunday best, never thinking they’d make it all the way. Members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference drew straws to see who would lead this march because they knew the possible dangers. They knew tension was boiling and they knew Sheriff Jim Clark could burst at any second. State troopers and a posse of men deputized by Clark were waiting on the other end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, turning the marchers around with violence, billy clubs, cattle prods and tear gas, beating the protestors back on what would come to be known as “Bloody Sunday.”

It was only 50 years ago that voting rights were granted to all American citizens. Before then, it was difficult for black Americans in the South to register to vote. They were quizzed with arbitrary questions like, “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?” Registrants had to pay a poll tax and get a previously registered voter to vouch for them. Less than 2 percent of the black population was registered to vote in Dallas County before the Voting Rights Act was passed.

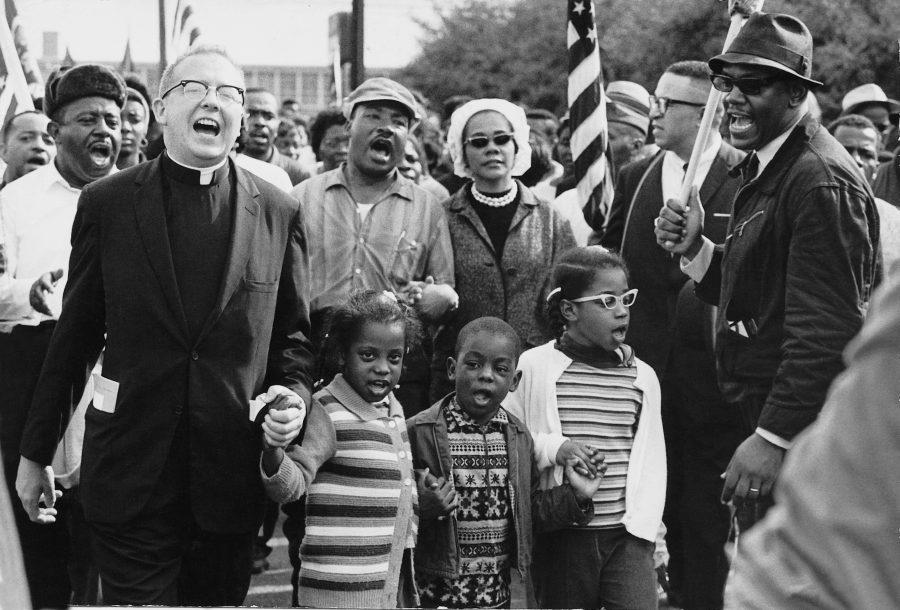

The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. knew voting rights were the key to equality. Without the vote, the people couldn’t make any change.

“If you didn’t have the power of the vote, you really had no power,” Jamie Wallace said.

Wallace, who graduated from Alabama in 1958, covered the events of Selma as a journalist.

The events of Selma only impacted The University of Alabama in small ways. No official statement was made and no reactions were documented, but the events of March 1965 were evidence of the receding tide of segregation.

“Alabama never had an event like Ole Miss where you had federal troops invade the campus and protect black students, but Selma was close in the sense that President Johnson had deputized members of the National Guard and sent members of the Army to protect King and the marchers,” John Giggie, a history professor at The University of Alabama, said. “So symbolically UA was forced to come to terms with the rapidly approaching end of segregation and the federal government’s hand in assuring the end.”

Giggie and Charles Mauldin, a foot soldier in the civil rights movement, both credit the journalists of the time, and said they contributed greatly to the movement.

“In many ways this was one of American journalism’s finest moments,” Giggie said. “If for generations before it had ignored the problem of racial tension [and] hierarchy in the South, at Selma broadcast and print journalism provided the type of push that democracy needed.”

Spider Martin was a photographer who spent weeks in Selma on assignment for The Birmingham News. He developed a relationship with many of the marchers, and King himself invited Martin to stand with him on the steps of the capitol in Montgomery as he gave his speech at the end of the march.

King has been quoted as saying, “Spider, we could have marched, we could have protested forever, but if it weren’t for guys like you, it would have been for nothing. The whole world saw your pictures. That’s why the Voting Rights Act was passed.”

King said people could have marched, picketed and boycotted, but no real changes were made until the greater public was made aware of the treatment black people were getting.

“People in the media, if they’re ethical, are sworn to try to tell the truth as well as they can and that is a truth that needed to be told,” Mauldin said.

Giggie said Civil Rights bills would probably have come along without journalist’s presence, but it would have come at a later date.

“There are times in U.S. history when journalism is absolutely essential to advancing the cause of democracy, and the Civil Rights Movement was one of those times,” he said.

Mauldin said one of the reasons King was invited to Selma was because they knew the media would follow.

“Had it not been for the media, Bloody Sunday wouldn’t have been televised nationally and internationally,” Mauldin said. “The impact of Dr. King’s call to come to Selma and stand up for right would not have been publicized.”

Mauldin joined in working with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and SCLC because of people like Bernard Lafayette. When Lafayette came to town, he got the school kids to question why things were the way they were. The movement in Selma was youth-based. Parents rarely questioned or challenged the authorities because they didn’t want to lose their jobs or their lives. They were conditioned to live this way and the only way to make change was for these groups to target the youth.

At age 17, Mauldin was head of the Dallas County Student Union. He said he wasn’t a natural born leader, but he had a very serious outlook on life and because of his commitment and integrity they voted him to lead the group.

“The American character is full of hope,” he said. “When people are hopeful, they do the right thing. The civil rights movement gave those people who wanted to be bigger than themselves an opportunity and come to the rescue of what was best about America. It called about the best of America’s character. People responded to injustice. Selma put a spotlight on the injustices. Once that was done, injustice couldn’t sustain itself. It was Selma that did that.”

Members of SCLC had visited Albany, Georgia, before going to Selma in hopes of gaining voting rights, but without any major incidents happening the word did not spread and nothing came of their marches. Meanwhile, SNCC was working hard in Selma laying the groundwork for equality.

The eight members of the Dallas County Voters League, known as the Courageous Eight, signed a letter inviting King and the SCLC to Selma.

“Selma at the time was the heart and soul of the economy in the Black Belt,” Wallace said. “It also had a solid organization for voting rights. People who had been working on this problem for months prior to this time and had very little success so they decided to invite Dr. King to come to Selma and to lead voting rights demonstrations.”

Mauldin said they needed the violent Sheriff Clark for the movement to succeed. It was openly discussed at that time and many were aware that Selma was chosen because of Jim Clark.

“It was sort of like how Jesus needed Judas,” Mauldin said.

At first they found his brutal tactics frightening, but soon they changed their minds.

“Once you gain the moral high ground, you lose your respect for people,” Mauldin said. “Then they can’t bully you. You don’t care what they do. We would not be intimidated by a bully like Jim Clark. We were willing to die on that bridge. Once people are willing to die for something, bullying doesn’t bother you that much.”

Sunday, March 7, 1965, when a crowd crossed over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the state troopers waiting for them on the over side warned them to disperse and when they didn’t they were beaten and tear gassed.

“The march itself placed emphasis on the fact that people were being denied the right to register to vote,” Wallace said. “When they stopped the march and the violence broke out it grabbed national attention. Up until that point it had been a local issue.”

Being able to vote led to being able to run for office. Wallace said the first black mayors of Detroit and Newark came from Alabama.

“Because of events in Selma, blacks were given civil rights and freedoms they were previously denied,” said Barnett Wright, an AL.com reporter and author of a book on the civil rights movement in Birmingham. “That had not only a positive impact on the state but the country as a whole.”

Fifty years later, in the wake of an Oscar-nominated film and Oscar-winning song, the nation’s eyes are once again on Selma. President Barack Obama will be in Selma to celebrate the anniversary of the march this Saturday.

“It reminds us, these many decades later, about the importance of this movement,” Giggie said. “We can argue over the historical accuracy but you can’t quibble with the power of that march, you can’t argue that this wasn’t a turning point in many ways for the movement.”

Now in 2015, the public faces similar issues with many of the acts that put equality in place being repealed under the idea that racism isn’t as prevalent as it was in 1965.

“One of the main themes of the Selma march is that it’s bridging the past and the present,” Giggie said.

Looking back, Giggie identified the crossing of the Edmund Pettus Bridge as a pivotal moment in American history.

“The blood spilled on that bridge baptized and birthed a new symbol, one that’s shorn of its segregation meaning and was infused with its integration potential,” he said.