A countless number of students have come and gone from the University of Alabama, but how many have ever wondered how the buildings they enter everyday got their names?

The buildings that surround the Quad have been named after everything from former Senators to former chapter presidents of the Ku Klux Klan.

“It’s not terribly surprising that the public figures for whom many of the University’s buildings are named held segregationist beliefs,” said UA professor and chair of the history department Kari Frederickson. “They were men of their time. To do otherwise in the period between 1880 and 1965 or so would have meant political suicide. With a few notable exceptions, proclaiming one’s support for white supremacist ideals was a requirement for public office during this period.”

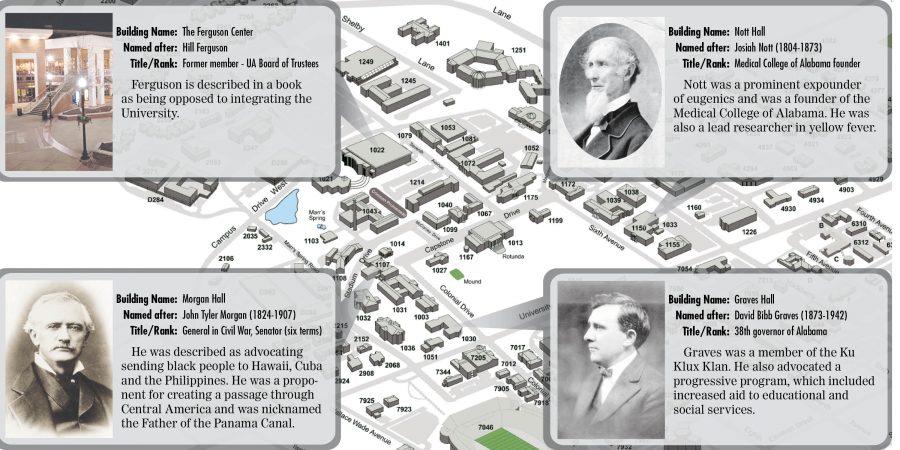

Morgan Hall, the current home of the University’s English department, was named after John Tyler Morgan, a brigadier general of cavalry in the Civil War and a six-term U.S. Senator.

In a novel titled “King Leopold’s Ghost,” author Adam Hochschild wrote that, “at various times in his long career Morgan also advocated sending them [black people] to Hawaii, to Cuba and to the Philippines.”

An article detailing Morgan’s life in the Encyclopedia of Alabama states that, “Morgan took ideas from Roger B. Taney, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, whose infamous Scott v. Sandford ruling in 1857 had reduced blacks to the status of livestock and presented them in new form with great effectiveness for those trying to prove the inferiority of blacks to whites.”

Morgan also thought it important for America to create a passage of travel through Central America and was ultimately nicknamed the father of the Panama Canal.

“Because this campus evolved during the time of the Civil War when racism was high, it is no surprise to me that racial issues continue to arise today,” said Jared Gray, a senior majoring in civil engineering.

Graves Hall, which houses the University’s College of Education, was named after David Bibb Graves, the 38th governor of Alabama.

A biography of Graves on the Alabama Department of Archives and History website says Graves was the Grand Cyclops, a high-ranking official, in the Ku Klux Klan.

The website also says Graves advocated a progressive program which included increased aid to educational and social services. New schools were built, funding for schools increased, and the price of textbooks decreased during Graves’ first term as governor.

“None of this is that shocking to me,” said Melanie Alexander, a sophomore majoring in biology. “We still have racial issues on this campus even today.”

Nott Hall, home to the Honors College, is named after American physician Josiah Nott.

According to UA history professor Lisa Dorr, Nott was a prominent expounder of eugenics—a set of scientific beliefs growing out of early genetics from the start of the 20th century to World War II that promoted improvement of the human race by encouraging advantageous breeding.

While eugenicists wanted model citizens to procreate with other model citizens, they also encouraged sterilizing the unfit as a way to prevent future social problems, she said.

“By sterilizing people who had things like epilepsy, alcoholism, mental illness, or even such things as immoral behaviors or criminality in their family trees, you could prevent those same problems in the future by preventing the birth of those who might have those tendencies,” Dorr said. “But they sterilized thousands of people without their consent, sometimes without even their knowledge.

“And the Nazis would eventually develop their ideas about treatment of the mentally ill, disabled, homosexual from our eugenicists.”

Nott was also a founder of the Medical College of Alabama, and a leading researcher on yellow fever, a disease which killed four of his children.

“Being that this campus was founded in a highly racist era, it doesn’t surprise me that there are racial issues that still present themselves quietly surrounding issues such as these,” said Chelsea Brunson, a junior majoring in biology.

Hill Ferguson, the namesake of the Ferguson Student Center, was a former member of the UA Board of Trustees.

In his novel “The Schoolhouse Door: Segregation’s Last Stand at the University of Alabama,” E. Culpepper Clark wrote that Ferguson opposed the decision to allow Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood to enroll at the University in 1963.

In a conversation about stalling the integration process with the president of Alabama College, Clark quotes Ferguson as asking “what defense he and his associates were setting up against the black clouds that were threatening.”

Clark also tells of how Ferguson “never gave up his quest to ‘keep ‘Bama white.’”

“So yes, unsavory characters have buildings named after them on campus,” Dorr said. “But I think the important lesson is to talk about those mixed legacies, rather than sweep them under the rug or immediately move to rename the buildings.

“It is far better to start a dialogue about why was it okay for people to hold these ideas in the past, and what factors ultimately changed us so that those ideas are no longer acceptable.”

Twitter box: What do you think about the origins of these prominent campus buildings? Tweet the hashtag #UAbuildings with your thoughts.