The United States’ judiciary may not be as accurate or safe as citizens may believe.

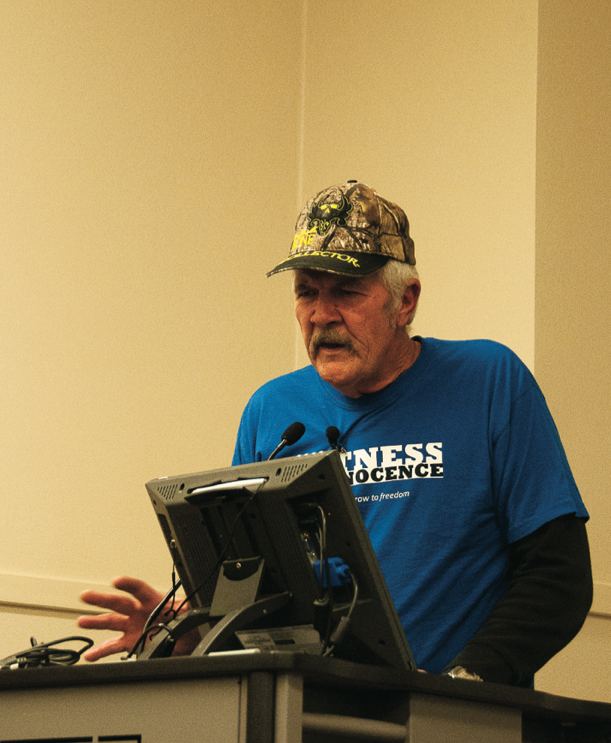

That was one of the main points capital punishment mitigator and University of Alabama School of Social Work faculty member Joanne Terrell and death row survivor Gary Drinkard made in a lecture titled “The Death Penalty from a Social Justice Perspective”on Nov. 14.

The two activists spoke to a full audience in ten Hoor Hall on Wednesday night to discuss the unfairness of the death penalty within the state.

Lending a personal perspective to the controversial subject, Drinkard recounted his experience of being wrongfully convicted for the robbery and murder of a junkyard dealer in 1995 and later sentenced to death. After writing numerous letters to organizations for help, Drinkard was able to assemble his own dream team of attorneys to prove his innocence. He received an acquittal in 2001.

Drinkard said his case is a prime example of a person convicted of a crime they did not commit and the injustices of the legal system in the state. However, it is not unusual.

“His story is not unique to Alabama death row,” said Terrell, who also serves as a mitigator for indigent capital murder defendants. “[The legal system] doesn’t care who did it, they just want to convict somebody.”

“At least 10 percent of people down in death row haven’t done it. It’s very discouraging,” Drinkard, who now acts as a lobbyist against the death penalty, said. “There have been 141 people let off of death row proven innocent.”

Although the legal system can be proven faulty, Drinkard and Terrell explained that it is especially so for low income people who can’t afford an experienced lawyer and become stuck with one who doesn’t care or doesn’t know how to handle the case. Additionally, someone is 10 times more likely to get sentenced to death row if it is a black-on-white crime.

“No rich person ever winds up on death row,” Drinkard said. “They have the money to get lawyers to get them out of it. The death penalty is racist and immoral.”

He also said the death penalty sends the message that some people have more value than others.

In addition to the numerous holes within the morality and legal complications of the death penalty, the speakers recounted the first-hand stories of the inhumane conditions of the death row in prisons. Drinkard said often administrators and officials turn their cheeks from the needs of the inmates.

“He said, ‘I can’t take it. It’s 103 degrees, I don’t even have any money to get a cold drink from the canteen. Last week someone died of a heat stroke, and the guards wouldn’t help him,’” Terrell said one of her defendants on death row said to her before he gave up fighting his case and dropped all of his appeals.

Although Drinkard also experienced the harsh realities of prison on death row, he did not give up fighting for his innocence, although he admitted he considered suicide.

“I distanced myself from death row. I wrote letters, watched T.V. I had penpals, and they would send me pictures, and I would project myself in their lives. It was my own world. But they knew me well there,” Drinkard said.

Drinkard and Terrell also provided ways students should become involved in speaking against the death penalty.

“You have to lobby Montgomery, there has to be an organized persistence. Normal people don’t know how the justice system works until it hits home,” Terrell said. “We need to find a way to fund the justice system across the board for all people in terms of socioeconomic ability. Another thing is we need to hold attorneys in both the prosecutor’s side and the defense side accountable for misconduct. Because the means do not justify the end.”