When Alex Flachsbart arrived at the University of Alabama in 2005 on a VIP visit with the Honors College, his first meeting was not at all what he expected. The first item on the agenda given to him by the Honors College was a visit with President Robert Witt.

“My father looked at me and said, ‘There’s no way you’re going to meet with the University president,’” Flachsbart said. “Then, at 9 a.m., they showed us into his office, and there’s Dr. Witt.”

Flachsbart is a California native, and in the fall of that year, he became one of the many out-of-state students who have helped propel the University’s enrollment to 31,000. He was also one of many who had been personally recruited by the UA president.

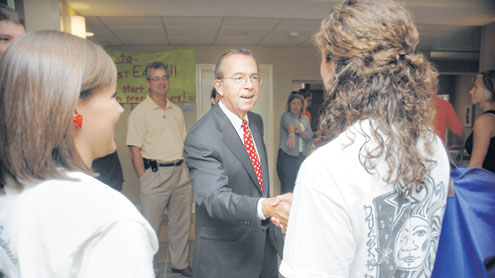

“If we had a student we were really going after, [President Witt] would always sit down and talk with the student over in his office,” said Robert Halli, who became the founding dean of the Honors College during Witt’s tenure. “None of the presidents that I’ve worked under, as far as I know, have been very involved with recruiting students. President Witt threw himself right into that.”

For Flachsbart, the initial meeting with Witt was the beginning of a long, close relationship with the UA president.

“I got to travel with Dr. Witt in the plane, and I probably visited at least 8 or 9 cities with him,” Flachsbart said. “He’s a much funnier guy than people give him credit for. He’s got this very sly sense of humor.”

Empowering students

Hank Lazer, the associate provost and director of Creative Campus, said that Witt’s leadership has enabled students to spawn several new initiatives, like Creative Campus, that draw more students to the University.

“If what you want to do is consistent with the institutional mission, given the brilliant fiscal leadership of Dr. Witt, we’ve been in a position to say yes to good ideas for students,” Lazer said.

Creative Campus is a student-centered arts advocacy organization that began in 2005, after a group of students in an Honors College seminar presented the idea to Lazer and UA provost Judy Bonner. It has since hosted several events, including Quidditch on the Quad and the Druid City Arts Festival.

“In a way, Creative Campus is a paradigm for how the University of Alabama creates personal relationships for students in smaller communities,” Lazer said.

“I think you could find that in Honors. You could find it in Blount. You could find it in New College. You could find it in the Center for Ethics and Social Responsibility. You could find it through numerous service organizations.”

Flachsbart said Witt wanted students to make an impact. “I think that the whole message of Dr. Witt’s UA experience was ‘come as you are and leave the campus as you want it to be,’” he said.

At times, though, Witt’s enthusiasm for student-led initiatives has manifested itself into deference on most all student-led initiatives, including the segregated greek system and the Machine.

“It is appropriate that all our sororities and fraternities — traditionally African American, traditionally white and multicultural — determine their membership,” Witt said when asked about continued segregation in the greek community last fall.

It was a surprising comment from an administrator who predicted a breakthrough in the integration of the greek system after first taking office in 2003.

“It’s difficult to be the first,” Witt said at the time. “If I was an African American and received a pledge from a fraternity or sorority, the first thought that’d cross my mind is, are they going to accept me and check off victory and that’s it, and how comfortable am I going to feel?”

While a black student was ultimately admitted to a Panhellenic sorority in 2003, the breakthrough Witt predicted never came. All of the black students who participated in Panhellenic rush in 2011 were dropped. Additionally, two new sororities with no black members, Alpha Phi and Delta Gamma, have been established on campus during Witt’s tenure.

When asked about the Machine later in Fall 2011, Witt again deferred to students.

“Any group of University of Alabama students has the right to organize for the purpose of exercising political influence,” he said.

Clark Midkiff, the outgoing president of the Faculty Senate, said he thinks administrators are reluctant to address issues with the greek community.

“I think part of it is because the great power and influence of the greek alumni,” Midkiff said. “All administrations have to be careful to try to gently ease change rather than try to precipitate really abrupt change.”

Midkiff said he believes President Witt wishes our fraternities and sororities were integrated but doesn’t believe in forcing integration.

“This is not a new problem,” he said. “I don’t think this is a President Witt problem.”

Racial tension and emails

Over the course of 2011, though, Witt emailed the student body three separate times in response to racially offensive incidents on campus. After Witt’s second email, the Social Work Association for Cultural Awareness invited students to participate in the Not Isolated March, which was intended to raise awareness about diversity and push for a more inclusive campus.

The march took place in October, just over a week after racial slurs were chalked on the Moody Music Building, the impetus for Witt’s email.

Adrienne McCollum, a senior in social work and the president of SWACA, said she invited many administrators, including Witt, to join the group at the Ferguson Center Plaza, which was the final destination of their march. McCollum said the only response she received was from Mark Nelson, UA vice president of student affairs, who was ultimately unable to attend the event because of a prior obligation.

“I did not get a response from Dr. Witt or any of the other administrators until maybe two weeks later,” she said.

McCollum said when she got the opportunity to talk to Witt, he was receptive of her ideas. She asked him to provide more detail in his emails and, when a fight broke out at the Delta Chi house between members of the fraternity and three black Alabama A&M students in November, Witt took her advice into consideration. The email he sent students that day was nearly three times as long as the 63-word statement he sent out last February, when a racial slur was yelled at a black student from another fraternity house.

Justin Zimmerman, the victim of that slur, said at the time he didn’t think Witt’s email did enough to address the issue.

“I am very grateful for the helpfulness and the apologies I’ve gotten…but the email that Dr. Witt sent was disappointing,” Zimmerman said. “It didn’t really get the whole situation, and it didn’t explain what happened and the perpetrators.”

“I think it was one of those situations were he thought that he was responding,” McCollum said. “He thought that sending the email and speaking out, so to speak, and saying this is not behavior that we condone at the University of Alabama…was what he was supposed to do.”

Prior to the Not Isolated effort, McCollum said all she knew of the UA president was his name.

“I didn’t know what he looked like,” she said. “The administrators need to figure out how they can make it clear to students that they are there for us and we can come to them with our ideas and suggestions and I think transparency is going to be the key to creating change.”

An administrator — and a person

“He sees things as a chief academic officer and as an administrator — and as a person,” said Marshall Houston, who graduated from the University in 2011. Witt served as a Houston’s faculty mentor throughout his time in college.

“I was able to understand that he may feel something as a president, and he may think something that may drive his decision-making.” Houston said. “But he also saw it as an academic and as a person.”

During Houston’s sophomore year, he decided to make a documentary about Foster Auditorium, the site of Alabama governor George Wallace’s infamous “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door.” Houston said Foster is a key part of the University’s history because students and administrators at the time drove the peaceful integration of the University.

“I met with [Witt] in December 2008 and kind of explained my thoughts of making a film about Foster Auditorium and about seeing what its role was,” Houston said. “I very much felt that the University needed not only to recognize it, because that’s too passive, but actively celebrate it.”

Witt responded by explaining the different perspectives through which he viewed Foster. First, as the University president, he had to consider the Board of Trustees and finance.

“I’m a little disappointed because here I am, this 19 year-old, committed to Foster Auditorium,” he said.

But then Witt explained how he saw the issue as an academic.

“The purpose of education and the purpose of higher education or academia is finding something you’re passionate about or you care about and exploring that to the fullest,” he told Houston. “However I can help you, I will do that.”

Houston said even though he knew the film was not going to reflect well on the University, Witt did everything he could to help him engage in the discourse about Foster, including having the building unlocked so that Houston could go inside.

Foster Auditorium was later renovated, and a new plaza commemorating the black students who were admitted after Wallace’s stand was constructed outside of the entrance. The plaza was dedicated in November 2010.

“It is the shining light of what can happen when a University makes a commitment to equality and justice,” Houston said. “I am so satisfied and happy to see the outcome of how we memorialize Foster Auditorium.”

He said Dr. Witt’s background allows him to see opportunities for the University that others don’t.

“He talked about his background and not being from Alabama, and he talked about how, because he was not from Alabama and because he had different experiences going to school and working in the northeast, it gave him another perspective on what is possible for us as a University,” Houston said.