Three professors at The University of Alabama are using data analytics to stop human trafficking in the Tuscaloosa area and across the United States.

Nick Freeman, an associate professor of operations management; Greg Bott, an associate professor of management information systems; and Burcu Keskin, a professor of operations management are working out of the Culverhouse School of Business. Their project is called the STANDD initiative, which stands for “Sex Trafficking Analytics for Network Detection and Disruption.”

According to The University of Alabama Institute of Data Analytics website, the initiative “aims to identify novel analytical techniques for grouping ad data across popular sites and deploying products that law enforcement agencies can use to more effectively battle sex trafficking.”

So far, the STANDD initiative has led to over 250 arrests for soliciting prostitution, over 50 arrests for traveling to meet a minor for commercial sex, and over 60 potential trafficking victims identified.

The first step in this process is collecting data from websites that offer commercial sex work. These websites often allow individuals seeking services to choose a location and see listings in the area. Because prostitution is illegal across most of the United States, many of these sites are hosted internationally, and although they prohibit sex trafficking openly, the listings are commonly presented as voluntary sex work online.

The volume of posts on these illicit websites can be overwhelming for individuals and organizations to comb through manually.

“Law enforcement oftentimes doesn’t have the time or the resources to bring down that data at the scale it is posted,” Freeman said. “We bring down about 100,000 ads every day.”

Using this data, the STANDD initiative has built a large database of commercial sex ads. STANDD can then analyze the data using machine learning, network science and graph theory to make connections and identify patterns.

One common and relatively easy-to-identify pattern is scam advertisements. Eliminating these ads saves law enforcement and nonprofit organizations considerable time and effort that would have been otherwise wasted.

Bott said it is practically impossible to identify from an ad alone if individuals are participating in sex work willingly or have been trafficked. By making connections within the data, STANDD can identify potential indicators that a person has been trafficked, but there can still be a lot of uncertainty about individual cases.

“Even if they [victims] are being trafficked, oftentimes it’s really hard to get a conviction because that requires the victim to testify against the trafficker,” Freeman said.

The STANDD initiative can pass on information about potential trafficking victims to law enforcement and nonprofit organizations. The West Alabama Human Trafficking Task Force, a joint effort by the University of Alabama Police Department, Tuscaloosa Police Department and Northport Police Department, has worked closely with STANDD on multiple occasions to aid potential trafficking victims.

Nonprofit organizations like the WellHouse and Trafficking Hope develop relationships with and provide long-term support to potential victims.

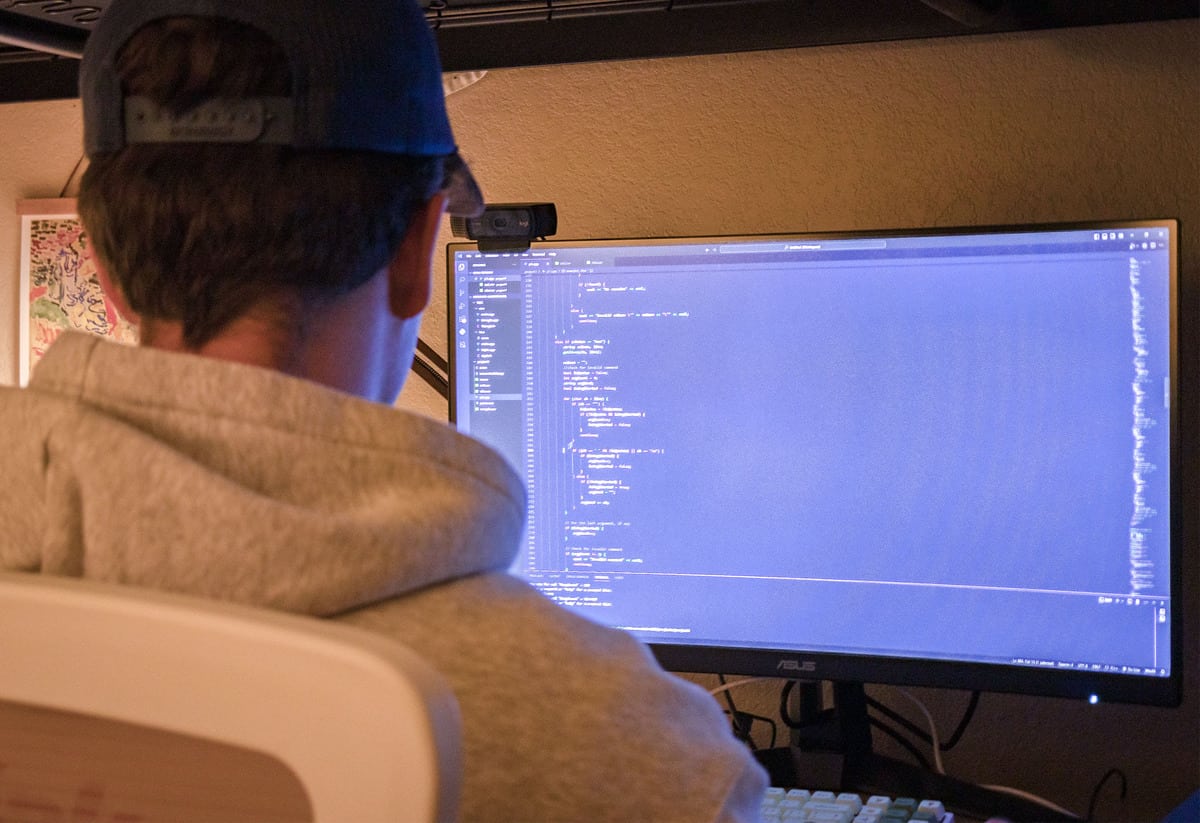

The program’s positive, tangible effects on the Tuscaloosa community have inspired multiple undergraduate students to help with the research.

“It is so awesome to see us be able to make an impact with code on the screen,” said Ellie Burton, a sophomore computer science major.

Helene Renninger, a sophomore majoring in economics and management information systems, joined the STANDD Initiative “because it was more than just research. It was research that was making an impact on people actively, and they had the numbers to prove it.”

Ella Foes, a junior majoring in mathematics and in the accelerated master’s program for applied statistics, said she enjoyed working on STANDD because it is “generally good” for people.

Currently, STANDD is developing techniques that use machine learning to notice patterns across advertisements about different individuals. The researchers hope to find stylistic choices in the ads that can act like a digital fingerprint, allowing them to identify posts created by the same individual. Doing so would help identify organized crime and traffickers with multiple victims.

“We found the individuals very well,” Freeman said. “But how can we identify commonalities that might point to a common trafficker?”

There are some limitations to what the STANDD Initiative can do. For one, STANDD can only get its data from online sources.

“The stuff that we see has to touch the internet, so if you don’t have a digital footprint, we don’t see you,” Bott said.

This makes the true number of human trafficking victims virtually impossible to know, even when looking at only the Tuscaloosa area.

“It’s hard to say how common trafficking is, because it is underreported for a number of reasons, but no place is immune, not even campus,” said Jessica Wilson, a UAPD investigator and part of the West Alabama Human Trafficking Task Force.

Bott, Foes, Freeman and Wilson all agreed that sensational representations of trafficking in media have distracted people from the reality of trafficking.

“Even if you’re aware that a lot of sex trafficking doesn’t look like that dramatized perspective, it can be hard to understand the weight and seriousness of other ways that sex trafficking shows up,” Foes said.

Sometimes the trafficker is a boyfriend or a family member, and frequently, the victims do not even realize they are being trafficked. Human trafficking can take many forms and affect any type of person with any background.

Wilson said, “If you aren’t aware of what trafficking actually looks like, you could miss it happening right in front of you and could potentially become a victim yourself.”

For some, the most concerning aspect is how common sex trafficking is.

“I grew up in Tuscaloosa, and it’s just been shocking because it’s everywhere,” Freeman said. “It’s in your backyard.”