Authors, directors and all other artists frequently find themselves on a journey — the pursuit of translating experience to content.

It is a noble quest. The infinite supply of human emotions, sensations evoked by occurrences good and bad, begs to be relayed to others. Without stories, whether written, put to film, photographed or simply verbalized, empathy and interpersonal relationships would be kaput, isolation reigning supreme in their place.

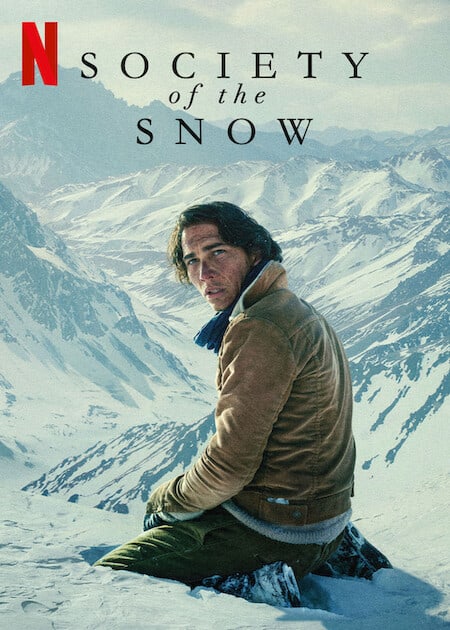

Truly capturing a felt experience is an elusive task; many would deem it impossible. Fortunately, J.A. Bayona’s “Society of the Snow” performs admirably.

Critical reception has been resounding: The film boasts a 91% on Rotten Tomatoes and a 4.1/5 on Letterboxd, as well as Oscar nominations for best international feature and best makeup and hairstyling. These numbers are a shiny front, evidencing a high-quality work. Beyond the praise is a loaded mantelpiece for Bayona; he delivers a caring appraisal of life, death, love and the significance of each.

The movie takes the widely known story of the Andes mountain crash, which stranded an amateur rugby team for two months, and gives it an unprecedented level of authenticity. What many will watch as an English-speaking film titled “Society of the Snow” is really “La sociedad de la nieve,” comprised of mostly Uruguayan and Argentinian performers speaking as the subjects of the real-life story would have spoken. Although obviously set in South America, it’s something of a fresh homecoming for Bayona, who hails from Spain but whose directorial career since “The Orphanage” — “El orfanato” — has been spent in Hollywood.

More than just cultural realness, the film is deeply rooted in the unromantic and erratic nature of life. There are no slow-motion sequences, no slow pan-ins as terrifying circumstances approach. Dramatic tension is derived from the merciless speed of those circumstances; whether it be an avalanche or even the initial crash itself, travesties occur on screen with the same real-life abruptness as they would have in 1972.

Bayona is constantly questioning the invisible intentionality behind life that so many love to assume. For a story featuring a rugby team dubbed Old Christians, it is a fascinating examination of faith — it neither claims the existence or divine influence of God nor tries to deny such ideas, rather letting the events play out and simply observing each character’s reaction.

Some have faith. Many begin with it and slowly move away. At one point, one of the survivors espouses a gut-punch of a monologue detailing how his concept of and belief in God has dwindled down to the level of those around him and their everyday goings-on.

The film’s patience and contentment with letting horrors be horrific simply by their nature is what makes it effective as a “based on a true story” outing. There is a gratifyingly low amount of editorializing; the narrative is for the most part aloof, and it accentuates the coldness of tone that matches the environment.

What sparing narration we get is itself an example of the movie’s brilliant grasp of how arbitrary life and death are in these sorts of survival stories. In “Society of the Snow,” the central narrator and the character who is played up to be the lead protagonist, Numa Turcatti, played by Enzo Vogrincic, winds up among the dead. The choice to grant him the power of narration even after his passing removes the typical notions of heroes surviving; in a freak situation like the Andes mountains crash, mortality doesn’t pick and choose based on character hierarchies.

The blunt and uncaring power of death is illustrated through another of the film’s technical strengths: its use of perspective. Most obvious in this category is the juxtaposition of characters in their dying state to flashbacks of full health to emphasize their digression. More subtle, however, are the unorthodox camera angles capturing the chaos of life or the wide, sweeping shots of snow-covered mountains where, symbolically for the characters’ predicament, not even the most eagled-eyed viewers can perceive the survivors.

Bayona takes this unromantic horror story and inserts love into the mix as the force that drives resolution. It is a narrative choice that maps seamlessly onto the story: The team finds itself in a place where many would succumb to conflict and descend into chaos, but through love for one another, as trope-ish at it sounds, they are able to find salvation.

Love is portrayed in a variety of ways. One survivor, whose wife was killed by one of the avalanches, talks about feeling amid his attempt to save her the most intense love he’d ever felt in his life. Turcatti’s final written words before passing were, “No hay amor más grande que el que da la vida para sus amigos” — “There’s no greater love than that which gives its life for its friends” — a paraphrase of a verse from the biblical book of John. As the movie progresses, teammates embrace each other with increasing compassion and fervent imperatives to keep on despite difficulties.

Cliched it may seem, but love is ultimately the reason the characters survive.

In a way, this dynamic combats the struggles with unbelief by providing a tangible endpoint. Answers might not be found by tormenting oneself with the question of “Why?”; as evidenced by a rescue brought about fundamentally by love, it could simply be about forgoing the need to know why things happen and simply dealing with each punch as it comes. In a story of good people chasing that elusive “why” behind so much of life and ultimately having no epiphanies, what could be more profound?