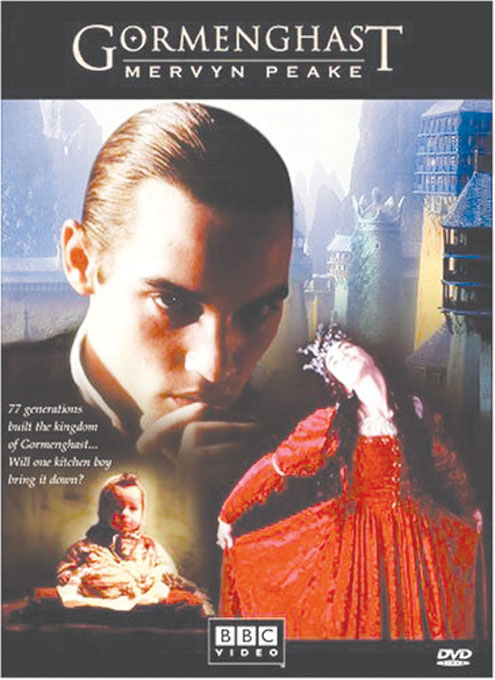

Four years in Tuscaloosa, and I’m beginning to despair that I am the only person on campus who has read Mervyn Peake’s “Gormenghast” series. I told myself last spring that if I got that Lifestyles columnist gig in The Crimson White, I had to do my best to remedy this (it’s a literary moral imperative) – but because I realize that I have in the past looked at zombies, supervillains and other science fictional pulp, let me make something perfectly clear: Mervyn Peake doesn’t deal in pulp sci-fi/fantasy. Mervyn Peake writes Literature with a capital L. Peake was an English artist, illustrator, poet and writer of the 1940s and 50s. The child of medical missionaries in China, a soldier in WWII, a war artist, an author and, tragically, a casualty of Parkinson’s Disease. Today he’s best-known for his Gormenghast series (comprised of “Titus Groan,” “Gormenghast,” “Titus Alone,” and the posthumous “Titus Awakes”). Although often categorized as fantasy, Peake’s writing leaves elves and wizards for lesser writers (here’s looking at you Tolkein). He has variously been called surrealist, gothic and the grandfather of steampunk. His oblique social commentary on authoritarian governments, psychology and insanity influenced the mad, metaphysical master Philip K. Dick himself, and continues to influence current authors in the “New Weird” movement (whatever that means). And to round out this litany, Peake’s books are widely, and rightly, considered classics by those Brits across the pond. So why aren’t we reading him in the States? My copies of “Titus Groan,” “Gormenghast,” and “Titus Alone” – acquired serendipitously at a used bookstore many years ago – have long since fallen apart, and are currently held together with scotch tape, staples and fond memories. They might not be pretty, but I personally think that the broken spine of a paperback is as good a testimonial as anyone can give to the quality of the writing inside. The Gormenghast series begins with the birth of Titus Groan, the 77th Earl of Groan, at an unknown time in an unknown country (and maybe an unknown planet). The setting, as well as perhaps the central character, is always and only Castle Gormenghast, Titus’s home. Gormenghast has a life of its own – a citadel the size of London, immutable, confining its denizens under shadowy arches and oppressive ritual since time immemorial. Mystical-sounding? Maybe. But Peake’s poetry and the Gormenghast books really are less about plot than their dreamlike (or rather, nightmarish) effect. While ordinarily I’m no fan of C.S. Lewis (he reminds me of a smug, modernist Thomas More), I can at least agree with his evaluations of “Gormenghast”: “Peake’s books are actual additions to life; they give, like certain rare dreams, sensations we never had before, and enlarge our conception of the range of possible experience.” Gormenghast is, like its name, grotesque, gory, ghastly, lyrical, monstrous, mind-bending and inarticulately beautiful. His characters are strange, sympathetic and Machiavellian by turn, and he names them with Dickensian flair (the scheming Steerpike, cadaverous Mr. Flay, day-dreaming Lady Fuchsia and sorrowful, sepulchral Lord Sepulchrave, for example). And always threading through this backdrop tapestry of bizarre characters are grand, sweeping themes: tradition as oppression, antagonist as anti-hero, freedom as madness. Like I said: it’s Literature.

Four years in Tuscaloosa, and I’m beginning to despair that I am the only person on campus who has read Mervyn Peake’s “Gormenghast” series. I told myself last spring that if I got that Lifestyles columnist gig in The Crimson White, I had to do my best to remedy this (it’s a literary moral imperative) – but because I realize that I have in the past looked at zombies, supervillains and other science fictional pulp, let me make something perfectly clear: Mervyn Peake doesn’t deal in pulp sci-fi/fantasy. Mervyn Peake writes Literature with a capital L. Peake was an English artist, illustrator, poet and writer of the 1940s and 50s. The child of medical missionaries in China, a soldier in WWII, a war artist, an author and, tragically, a casualty of Parkinson’s Disease. Today he’s best-known for his Gormenghast series (comprised of “Titus Groan,” “Gormenghast,” “Titus Alone,” and the posthumous “Titus Awakes”). Although often categorized as fantasy, Peake’s writing leaves elves and wizards for lesser writers (here’s looking at you Tolkein). He has variously been called surrealist, gothic and the grandfather of steampunk. His oblique social commentary on authoritarian governments, psychology and insanity influenced the mad, metaphysical master Philip K. Dick himself, and continues to influence current authors in the “New Weird” movement (whatever that means). And to round out this litany, Peake’s books are widely, and rightly, considered classics by those Brits across the pond. So why aren’t we reading him in the States? My copies of “Titus Groan,” “Gormenghast,” and “Titus Alone” – acquired serendipitously at a used bookstore many years ago – have long since fallen apart, and are currently held together with scotch tape, staples and fond memories. They might not be pretty, but I personally think that the broken spine of a paperback is as good a testimonial as anyone can give to the quality of the writing inside. The Gormenghast series begins with the birth of Titus Groan, the 77th Earl of Groan, at an unknown time in an unknown country (and maybe an unknown planet). The setting, as well as perhaps the central character, is always and only Castle Gormenghast, Titus’s home. Gormenghast has a life of its own – a citadel the size of London, immutable, confining its denizens under shadowy arches and oppressive ritual since time immemorial. Mystical-sounding? Maybe. But Peake’s poetry and the Gormenghast books really are less about plot than their dreamlike (or rather, nightmarish) effect. While ordinarily I’m no fan of C.S. Lewis (he reminds me of a smug, modernist Thomas More), I can at least agree with his evaluations of “Gormenghast”: “Peake’s books are actual additions to life; they give, like certain rare dreams, sensations we never had before, and enlarge our conception of the range of possible experience.” Gormenghast is, like its name, grotesque, gory, ghastly, lyrical, monstrous, mind-bending and inarticulately beautiful. His characters are strange, sympathetic and Machiavellian by turn, and he names them with Dickensian flair (the scheming Steerpike, cadaverous Mr. Flay, day-dreaming Lady Fuchsia and sorrowful, sepulchral Lord Sepulchrave, for example). And always threading through this backdrop tapestry of bizarre characters are grand, sweeping themes: tradition as oppression, antagonist as anti-hero, freedom as madness. Like I said: it’s Literature.

Categories:

The Gormenghast Series

October 31, 2011

More to Discover