Crowned

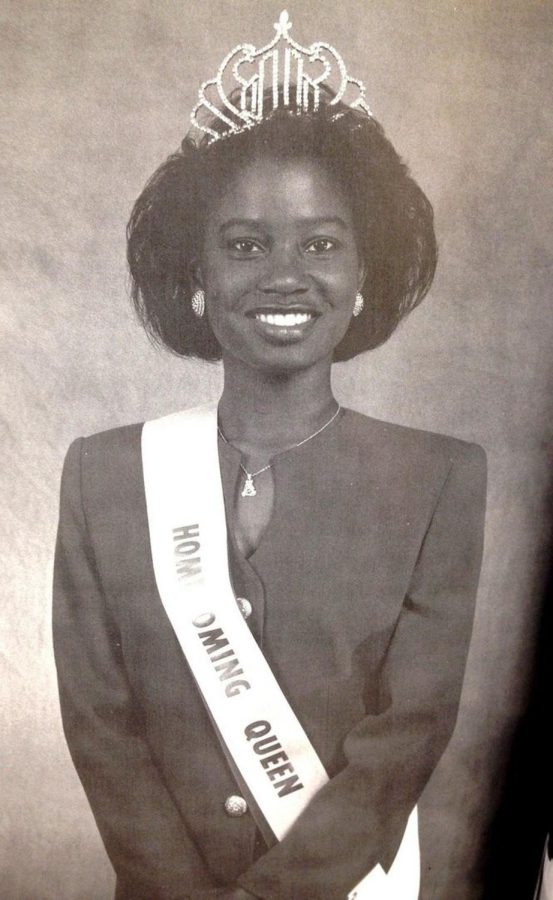

Pictured: Christa Hardy

October 20, 2021

As homecoming takes place at the University, we are swept with the air of tradition. Long-standing activities, competitions, parades and more await the student body every year in October. While students look forward to a good game of football, they also prepare for a much more charming and, at times, political tradition. That is the selection of the homecoming queen.

Competitions of this nature have long had the stereotype of “all beauty, no brains,” but this is not the case at the University. Each hopeful homecoming queen must have a social platform, a strong educational standing backed by a favorable GPA, and time to serve her campus. The queen is expected to represent The University of Alabama and its student body as campus celebrates another year of excellence. Yet there is a long history of underrepresentation within the competition itself.

Black students have steadily taken part in the homecoming queen elections since Dianne Kirksey became the first Black member of the court in 1970. Terry Points-Boney became the first Black homecoming queen in 1973, with Christa Valencia Hardy being the most recent Black queen in 1993. In this 28-year gap, a Black student has been on the court every year representing causes and spaces that are close to their hearts. This includes Jordan Watkins, who ran in 2018.

“I wanted to showcase the importance of mentorship, unity and inclusivity by contributing to diverse avenues of representation at The University of Alabama. Running for homecoming presented me with the phenomenal opportunity,” Watkins said.

Watkins, a two-time graduate of the University and current doctoral candidate, centered her platform around Upward Bound, a community-based organization that focuses on creating resources and providing support in science, mathematics, foreign language, college entrance and more. She has hope for better representation soon.

“I was not only advocating for mentorship and the impact I have personally experienced but the tremendous impact it had left on countless amounts of students at UA, and because of this, yes, I felt as though I played a hand in representing a cause bigger than myself and the Black community on The University of Alabama’s campus,” Watkins said.

One might ask: How has campus gone 28 years without a Black homecoming queen? It certainly isn’t due to a lack of effort.

Judy Burroughs was a member of the 2016 homecoming court.

“To be honest, I had no intention of running until my friend suggested I do it,” Burroughs said. “I was definitely nervous because I didn’t think I made that big of an impact on campus, but I had a lot of support along the way.”

Burroughs was no stranger to conflict as an established student leader on campus. She recalled a tense incident during her campaign run.

“One instance in particular was someone getting on my car while they didn’t notice that I was still in it. They were trying to erase my ‘Vote for Judy’ sign on my car. I called UAPD, but that didn’t do much. I also got a phone call saying I was ‘too dark’ to run,” Burroughs said.

She didn’t expect the campus to notice that she was running, but she talked to campus resources and decided to keep moving forward.

This year’s homecoming festivities will be no stranger to representation. Savanah Lemon and Noelle Fall both made strong bids for homecoming queen, both being heavily involved and representing historically Black sororities.

Regardless of what the future holds for Black homecoming queens at the University, we cannot forget those who came before. Terry Points-Boney, Joan Belinda Turner Woodard, Deidra Chastang, Opal Atonita Bush Butler, Kim Ashley and Christa Valencia Hardy created a legacy that will be remembered. They broke away from a perceived standard and held their crowns high.

This story was published in the Legacy Edition. View the complete issue here.