Why a group of Alabama students banded together against state prisons

The members of ASAP, fittingly enough, want change now.

March 24, 2021

Alabama Students Against Prisons (ASAP), an organization founded by multiple students over Zoom last December, has grown into a movement of young people working to put an end to what they believe is a prison crisis in the state of Alabama.

David Zell, a junior political science major at The University of Alabama, is one of the founding members of ASAP. He helped create the organization to represent student perspectives on incarceration and to protest Governor Kay Ivey’s leasing of two new private, mega-prisons in the state, costing $3 billion over 30 years.

“We are the generation that’s going to foot the bill for this 30-year deal,” Zell said. “We are the generation that’s going to really grow up with – and live with – the consequences of the choices that lawmakers make today.”

Governor Ivey released a statement after the lease agreement was reached.

“Leasing and operating new, modern correctional facilities without raising taxes or incurring debt is without question the most fiscally responsible decision for our State, and the driving force behind our Alabama Solution to an Alabama Problem,” she said. “We are improving public safety, providing better living and working conditions, and accommodating inmate rehabilitation all while protecting the immediate and long-term interests of the taxpayers.”

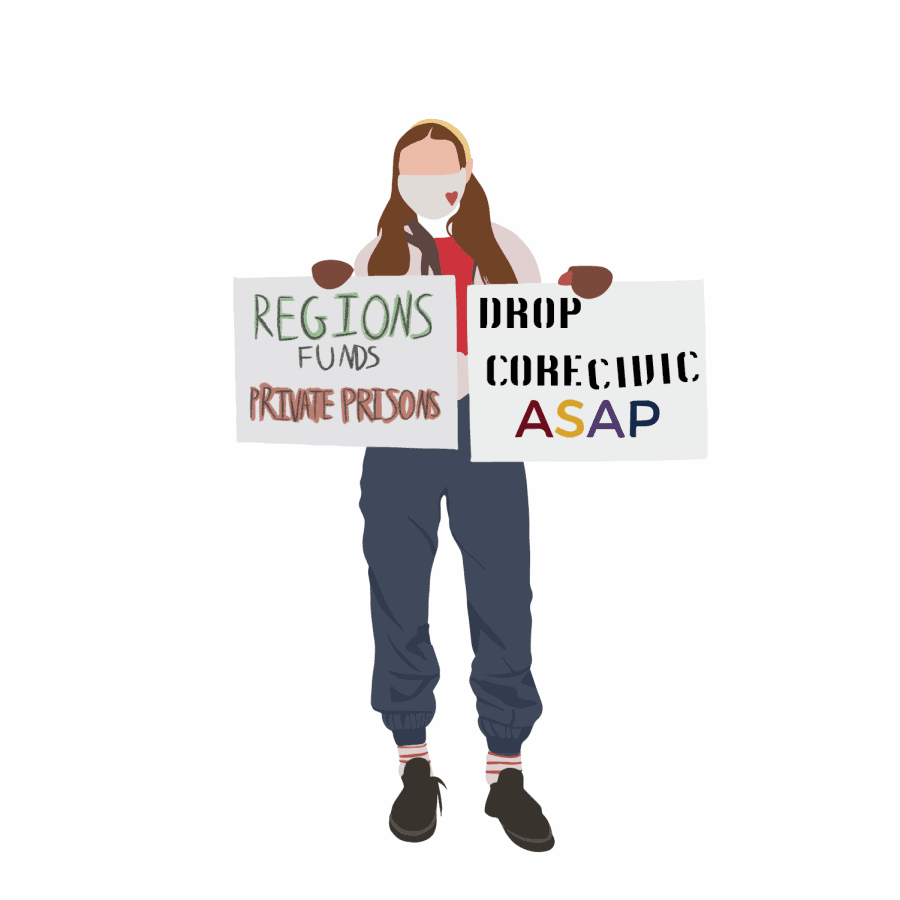

ASAP organized a campaign urging Regions Bank to divest from CoreCivic, one of the companies building prisons in Alabama. ASAP members realized that one of the five banks funding CoreCivic was headquartered in Birmingham. They staged a protest in December 2020, organized on social media, phone banked, got people to boycott the bank and worked with Black Lives Matter Birmingham. After meeting with ASAP, the Regions Bank executive team ceased funding for CoreCivic.

Hannah Krawczyk, a senior majoring in public administration at Auburn University and another founding member of ASAP, said the expansion is a bad idea for Alabama.

“There’s the human harm that’s going to come from building three new mega prisons, but it’s also about refusing to address the actual issues at hand, as people are locked up for decades in an environment that is not safe,” she said. “Being in an Alabama prison is a matter of life and death.”

In 2018, Alabama prisons had a homicide rate 600% greater than the national average. Sexual abuse, drug overdoses, inadequate mental health treatment and uncontrollable violence have been reported in prisons across the state.

Since its success with the Regions Bank campaign, ASAP has grown into a 300-plus member organization. Actions like protesting, writing op-eds, hosting letter-writing campaigns and organizing regular meetings have kept people engaged. Zell said he wishes that Alabama lawmakers had the same level of engagement.

“I just wish every lawmaker in the state would read the DOJ lawsuit and report,” he said. “Those documents are nothing more than a scathing critique, not of overcrowded prisons or decrepit infrastructure, but of a department of corrections that is structurally incapable of running prisons.”

Stef Bernal-Martinez, community outreach manager at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Alabama, said the ACLU wants to decarcerate Alabama’s prisoners and is pushing for a repeal of the Habitual Felony Offender Act, a law that requires a life sentence after three prior convictions. She said they are also in opposition to the construction of new prisons because “if you build them, they will fill them.”

“I wish they would do their job,” Zell said. “I wish they would actually work on developing a solution to this problem and not just putting a bandaid on a bullet wound. It’s just so painful to watch Alabama fall behind in something else.”

Krawczyk said the policy is only one of the only things ASAP is fighting for.

“Until the people in power recognize that they cannot criminalize and incarcerate every single person they possibly can, then we can’t have substantive change that’s going to address our prison crisis,” she said. “I think the biggest thing is just a mindset shift. We can’t continue to keep incarcerating people the way we do.”

ASAP has garnered media coverage from around the state and created a social media presence that works to highlight its mission.

“I think that ASAP’s biggest contribution is mobilizing young people,” Martinez said. “They get people excited. They teach people about what is going on and the way that they are building connections across the state is really authentic.”

Zell said he thinks there is an immense amount of power in being a student and that people want to hear the voices of the next generation. He stressed the importance of finding groups to join.

“No one can go up against a massive private prison corporation alone,” he said.

Organizations have been fighting this issue for decades, and Martinez said she’s noticed a shift in the demographics of young organizers.

“I think that young, Black people and young people of color have experienced this and felt politically activated for decades,” she said. “I feel like white students are starting to sort of understand that their futures are also tied up in the liberation of Black and brown folks.”

Krawczyk said her drive to work on ASAP everyday comes from believing that “there is a better future for all of us.” Zell said he has a similar motivation.

“I’ve got a lot of Alabama pride,” he said. “I really love this place and I want to live here for the rest of my life. This is part of my quest to help make this state one that I can be proud to call home.”