“I feel like I could tell the weather was getting bad,” said Tuscaloosa musician Joshua Folmar.

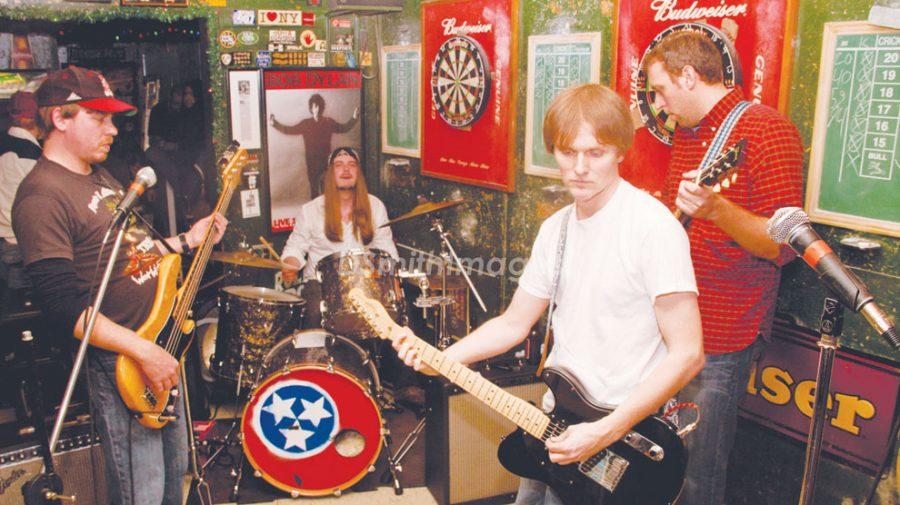

Folmar and I are standing right outside of Egan’s as he recounts the story of what happened to him on April 27, 2011.

“My manager was there with his wife and kid. I remember playing around with his kid and I was telling him, ‘Say hi to the tornado for me.’ And when I walked outside, I felt something was a little bit off. I remember the way the weather felt because that’s something that sticks with you.”

On the day of the tornado, Folmar was closing up shop at Oz Music as the storm hit Tuscaloosa. While the storm didn’t affect his workplace, he was soon to find that it would affect his life.

“Nothing happened [where I was], because it didn’t head that way,” Folmar said. “I started getting all of these texts and everything – it was very random and sporadic – but the only phone call that came through was the girlfriend of my roommate.”

The call Folmar received was a notice that his house had been destroyed and his roommate was trapped inside.

“At that point, my military mode kicked in, and I barreled out of the parking lot,” Folmar said. “I took an alternate route to get there and there were just trees everywhere. There were six trees in the road itself, so I had to park somewhere else and just jump over trees. I finally got to my front yard, and I couldn’t recognize it. I screamed out for my roommate, and he was maybe 10 feet away from me, but I couldn’t see him because of the trees. He’d already gotten out, thanks to the help of his neighbor. We just hugged each other and thanked God we were alive.”

Folmar’s military mode is from his work in the Marines, and his training certainly came in handy in the days after the tornado. However, he admits that the training hardened him to feeling like he couldn’t react to what happened. He said that if a thought like that came into his head, he felt it would defeat the purpose of helping those in need, despite essentially having nothing himself.

“I remember drifting in and out of sleep that afternoon, knowing that the weather was going to get bad,” said Blaine Duncan, who would perform at Egan’s later that night. “And then it appeared on the screen, when they showed the storm from one of the cameras in downtown Tuscaloosa. It appeared like it was starting to get bigger. I told my roommate that he may want to look at this, and then we were kind of scrambling as to what to do. Soon after, the camera feed went out, and then our power went out. That’s when we knew. It got eerily silent, and we knew it was probably headed near to us.”

Duncan lives a few blocks away from the hard hit region of Forest Lake, but his house remained intact from the storm.

“I can remember while I was sitting there and it came through, and the house started creaking,” Duncan said. “I fully expected the vent above us to fly out and hit us. Luckily, we only had a window that was busted open.”

In the days following the storm, both Folmar and Duncan wrote songs with the storm as a key backdrop. Folmar’s song “Job” plays on the Biblical tale of Job, who lost virtually everything over the course of his life but never gave up his faith. Duncan’s song “Numbers on Your Door” tells of how one man copes with what happened.

“I believe that music comes from the darker side of our nature, with the idea of pain and tragedy,” Folmar said. “That’s why comedians can be funny as hell, because they’ve gone through the worst.”

Both songs were written after Folmar and Duncan had gone long periods of time without writing any songs.

“I did my best to really take care when writing that song and crafting it to not be cheesy or asinine,” Duncan said. “The events weren’t motivation or inspiration, but writing that song opened something. I also tried to take great care in not speaking for everyone. It was just one guy’s point of view, and I tried to avoid clichés. I can’t speak for a whole group of people, and I dare not.”

Tragedy speaks to us because we feel we must respond to it. Music helps us to recover because it centers our feelings and is a coping mechanism. When art is truly transcendent, we help our fellow man reconcile tragedy.