A trip to the archives: Here’s how three CW editors covered segregation on campus

December 5, 2019

The University of Alabama, a campus that was built and maintained by enslaved people, did not open its doors to African American students until 1956, two years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision. The University did not grant a degree to a black student until 1965, when Vivian Malone Jones, who enrolled in 1963 with James Hood, became the University’s first African American graduate.

The Crimson White, the all-white student newspaper, covered and wrote editorials about integration on and off campus, garnering several awards and national recognition. While the paper was rarely critical of UA administration and devoted ample space to the voices of officials, editorial commentary condemned white violence on campus and supported integration, a stance that was met with resistance from several white readers.

Nelson Cole, 1955-1956

Autherine Lucy Foster, the first African American student to enroll at the University, spent her third day of class holed up in a tunnel connected to Graves Hall as a mob of over 1,000 protested her enrollment. Later that day, on Feb. 6, 1956, she was escorted, face-down, in a patrol car to the safety of a nearby barbershop, and the University suspended her “for her safety.”

On Feb. 7, Byron De La Beckwith, a Son of the American Revolution from Greenwood, Mississippi, wrote a letter to UA President Oliver Carmichael, stating that he was “delighted to see that the student body of your school protests integration.”

“Being a little bit integrated is just like being a little bit pregnant!” De La Beckwith wrote in the letter. “I trust you will do all in your power to see that segregation is maintained. Segregation is a right and privilege that all men must cherish and preserve at all cost! Get that ‘c–n’ off the campus. If you can’t, call on the Citizens Council – join it!”

De La Beckwith ended his note asking how to get in touch with The Crimson White, which was led by Editor-in-Chief Nelson Cole.

According to “The Schoolhouse Door: Segregation’s Last Stand at the University of Alabama,” which was written by E. Culpepper Clark, a former UA dean, Carmichael had acquiesced to the mob in expelling Lucy Foster. The Board of Trustees later decided that they would not readmit Lucy Foster without a court order. But, when a court order for her reentry was served, the board permanently expelled Lucy Foster, citing that she had “slandered” the University.

According to Clark, even Cole’s guarded affirmations of trust in the Board attracted hate mail and calls from those who supported the mob. Cole, who had written several editorials and was featured on the Today Show following Foster’s expulsion, pledged support for Carmichael and the Board of Trustees.

“If anything can be done, they will do it,” Cole said. “If nothing can be done, we still believe they will choose – and have chosen – the wisest approach to the problem.”

Mel Meyer, 1962-1963

James Meredith, who would later go on to become a civil rights activist, was barred from attending the University of Mississippi in 1962. Under the leadership of Editor-in-Chief Mel Meyer, The Crimson White published an editorial stating that black students had legal rights to attend Southern universities.

It was reported that, due to threats from the Ku Klux Klan as the result of the editorial, two private detectives were hired to protect Meyer for the remainder of the semester. The editorial, titled “A Bell Rang” and published on September 27, 1962, called for Meredith to be admitted.

“Morally, there is no justification for his rejection,” it read. “Legally, there can be no doubt he is entitled to become a student at Mississippi.”

James B. Laseter, chairman of the West Alabama Citizens Council, wrote to the then-head football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant and to the then-University of Alabama president Frank Rose in 1959 to oppose the team’s upcoming game in Philadelphia against Penn State’s integrated team.

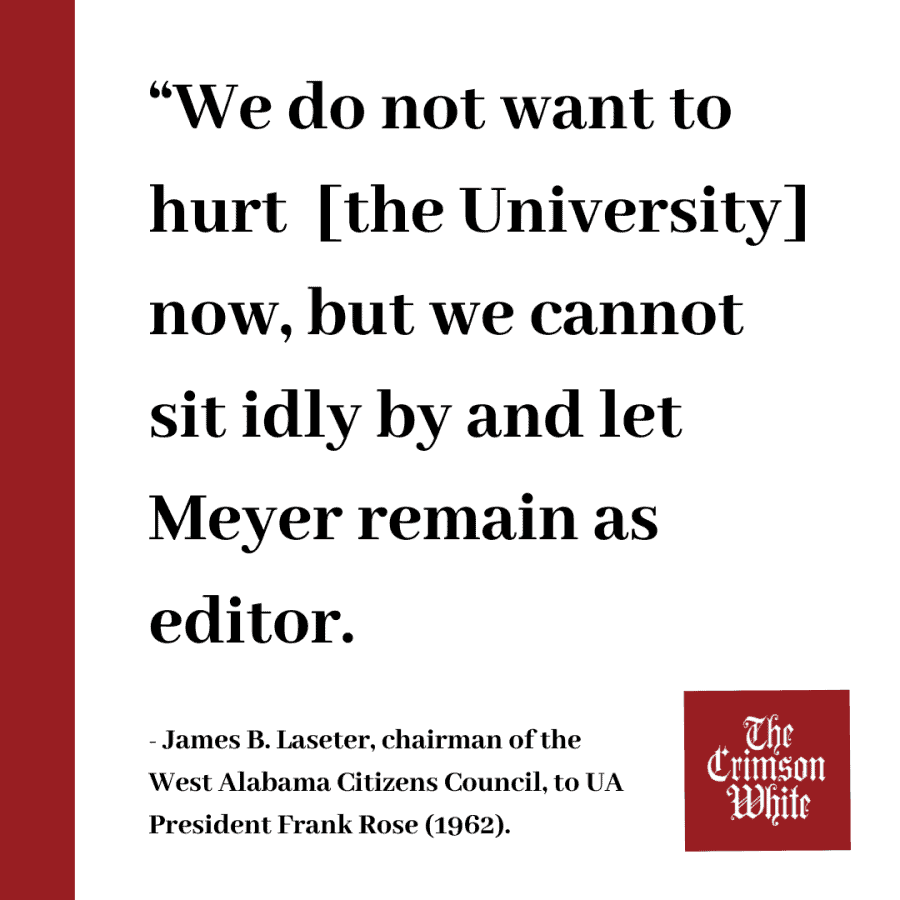

After the CW published editorials criticizing the West Alabama Citizens Council, Laseter called for Meyer to be removed as Editor-in-Chief from the CW.

“We do not want to hurt [the University] now, but we cannot sit idly by and let Meyer remain as Editor,” Laseter said to President Rose.

Walter Givhan, another citizens council member, wrote to the Board of Trustees requesting the ouster of Meyer. In meeting minutes from that 1962, Trustee McCorvey stated that he “expected to write Mr. Givhan to the effect that he was sure the University would handle the matter in proper course and that he had full confidence in Dr. Rose and in the way in which he was handling the matter.”

In efforts to diffuse the situation, Rose stated that Givhan had not written the editorial. After publishing the editorial, the paper’s staff, Clark wrote, “backed away,” falling “silent” on race in the following months, where they failed to chronicle momentous events of integration and racial strife at nearby universities.

Meyer received several journalism awards for his time as the CW editor, including the 1963 Editor of the Year Award from the U.S. Student Press Association.

Hank Black, 1963-1964

Hank Black is a Tuscaloosa native and a graduate of The University of Alabama who currently focuses on coverage of the environment. On April 26th, 2019, he was inducted into the UA Office of Student Media’s Hall of Fame, where he noted that the climate crisis was today’s most pressing issue.

Black has experience covering crises. As an editor at The Crimson White, Black reported on Governor George Wallace’s 1963 Stand in the Schoolhouse Door, where he refused admission to Malone and Hood, who had attempted to integrate the University seven years after Lucy Foster’s expulsion.

“Already, before that day, as Hank has written, he had met Vivian Malone and Jimmy Hood in secret sessions at Stillman College in Tuscaloosa,” the CW’s 1977 Editor-in-Chief and current editorial advisor Mark Mayfield told Birmingham Watch. “Those meetings brought together black students interested in enrolling at UA and currently enrolled UA students who supported them. The meetings were held in secret because of the threat of violence. After all, the KKK was headquartered in Tuscaloosa at that time.”

Mayfield lauded the leadership of both Black and Meyer, whose term preceded Black’s.

“The Crimson White’s efforts in objectively covering civil rights issues – and using the editorial page to strongly support integration – took courage and leadership,” he said. “Hank and Mel Meyer, the 1962-63 CW editor who preceded him, were the right editors at the right time in the CW’s history.”

Andrew Littlejohn contributed to the reporting of this story.