10 Year Column: “Glee” hit most of the right notes

June 21, 2019

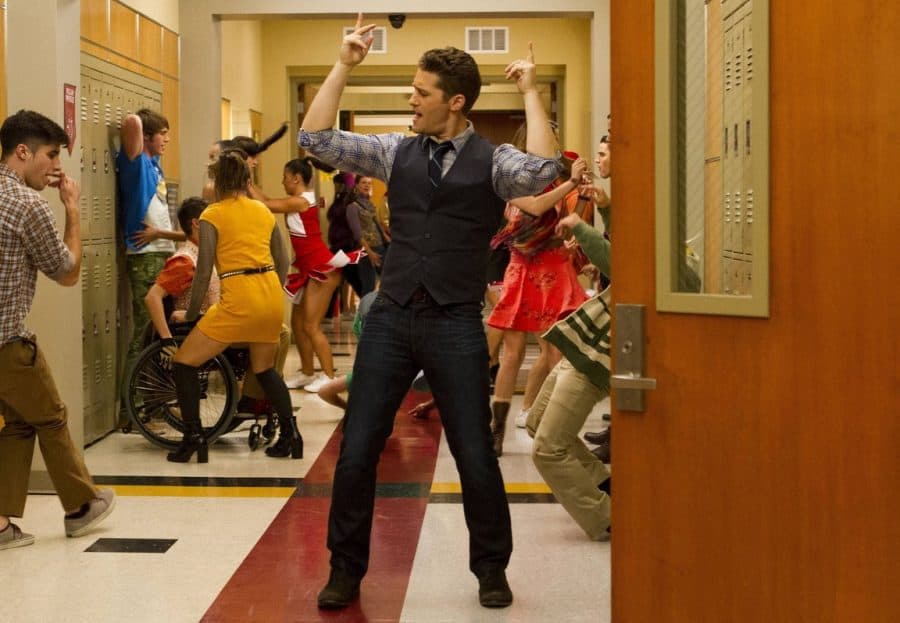

The premise is as follows: one jock, one cheerleader, one theatre nerd, one gay boy (only mildly risqué for primetime network television), one powerhouse vocalist, one goth kid and one wheelchair user are bonded together by their membership in the high school glee club. Plagued by harsh bullies and gas station slushies being thrown in their faces, they triumph under the leadership of a new choir teacher.

This is what Ryan Murphy, Ian Brennan and Brad Falchuck pitched to network executives in the late aughts, a television treatment based on Murphy’s earlier idea for a screenplay. The show would go on to attempt encompassing much more than a stereotypically ragtag group of high school students attempting to win show choir competitions. Sprinkled in were notes on poverty, teen pregnancy, racism, transgender identity and marital discord. Also, it was a musical.

Glee, for all of its specificity, was an amalgamation of every idea anyone had ever had for a television show about high school, plus Billboard Hot 100 covers and occasional attempts at show tunes.

The first big song featured on the show, a cover of Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’,” infiltrated pop radio into the 2010s. Its success was such that the show would later do a six-minute medley of other Journey songs—a tribute not so much to the band in question, but to the show’s own success.

Humorous beats could be interrupted by Amber Riley’s take on “Bust Your Windows,” a truly compelling musical moment from one of the show’s strongest soloists; scenes that were set up to be heartfelt could come crashing down with a rendition of “You’re Having My Baby,” certifiably one of the worst songs ever written in the English language. Murphy, the show’s primary showrunner, walked the fine line that separated utter parody and emotional drama in each and every scene. The show was billed as a comedy for awards season purposes, but each episode also ran an hour long and was known to feature tear-jerking comings-out, heartbreaks and school shootings.

It was that strangely ambitious pacing that led the show to run through countless complicated conflicts in its first three seasons, all of which kept the original cast members safely tucked away in their glee club classroom. As the show began to branch out, Lea Michele’s Rachel goes off to school in New York while other choir members stumble along in their Ohio hometown, lingering around the high school in an attempt to maintain the show’s ecosystem. Rachel is soon joined by some of her other fellow graduates in New York, and the show struggles to split its time between the two cities, juggling both its mainstays and a slew of new characters that have been introduced both in Ohio and New York.

Chemistry in the central romances of the show—former high school theatre geek Rachel and high school football heartthrob Finn, and emotionally open Kurt and rival school flirt Blaine—fizzles out the same way any high school relationship would, but the show doesn’t manage to find suitable replacements. The love stories and romantic conflicts that were once deftly woven into each teleplay chug along uninterestingly. When they manage interesting developments, they come as a jolt, as when Rachel unwittingly ends up in a relationship with a sex worker—whom she immediately dumps after finding out about his occupation, a surprisingly anti-sex work choice from a show that attempted to promote inclusivity and representation.

“Glee” came to a weary end after six seasons. The penultimate season, airing in 2013, featured an episodic tribute to Cory Monteith, the actor who portrayed McKinley High School quarterback Finn. Monteith died earlier in 2013 after a lengthy battle with substance abuse, which led to the end of the show.

With a special two-hour finale airing in 2015, featuring numerous cameos and appearances from old cast members, “Glee” died as it seemed so often to live: in celebration of itself.