By Caroline Smith | Staff Reporter

Alabama is a state painted with the pain of oppression. Even The University of Alabama is spotted with sites and symbols that harken back to a time when human beings were blatantly treated as inferior simply because of the color of their skin. Indeed, the civil rights movement is far from over, but new chapters are being written in Alabama’s story of progress.

Lately, a few milestones have been made in Alabama that alter the conversation about racial equality. In January, Oprah Winfrey journeyed to Abbeville, Alabama to visit the grave of Recy Taylor, an important, yet lesser-known figure in civil rights history. Additionally, the Equal Justice Initiative is creating the first memorial in the U.S. dedicated solely to victims of lynching. Both of these occurrences highlight the lives of those who influenced the civil rights movement but are not mentioned in the average history textbook.

“The more interesting stories, the more challenging stories are the ones that kind of happen in a more communal setting,” said Athena Richardson, a second year master’s student in American studies at The University of Alabama with a certificate in museum studies. “They aren’t the superstars but they are the ones who are really on the forefront, doing the work, challenging the status quo and the norms.”

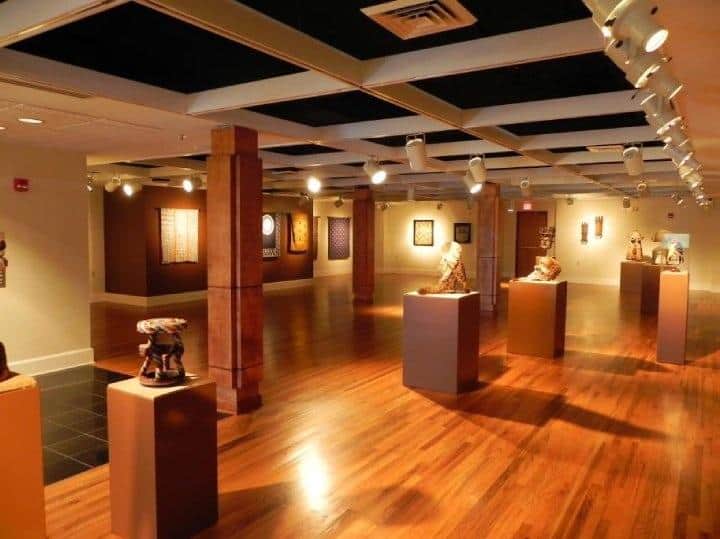

The monument to lynching victims as well as a museum that focuses on slavery, lynching and segregation will open on April 26 in Montgomery. They are called the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and The Legacy Museum, respectively. These projects are the result of years of detailed research. Each person’s story is told in as much detail as possible in order to humanize those who have been nameless for so long.

“This is a process where you are putting together scraps of material and quilting it into this tapestry to create a biography,” said Hilary Green, assistant professor of history in the department of Gender and Race Studies. “That form of recovery is not easy, and it’s not quick.”

These projects plan to shed a great deal of light on many impactful stories. However, besides the copious, time-consuming study involved, many question why it has taken so long for the U.S. to dedicate such a monument.

“I think just going back to what we learn in high school about black people fighting for civil rights is very little,” said Brie Smiley, a junior African American studies major. “We talk about slavery and we talk about Jim Crow, but then we go to the Civil Rights Movement, and there’s no mention of the violence. So, I think it’s important that we have it. And to answer why it took so long, I think it’s because it’s something that’s not arbitrary. It’s just blatantly violent. It can’t be contested.”

Despite its challenging nature, the general consensus is that the museum and monument will benefit the community and the ongoing Civil Rights Movement as a whole.

“Well it’s a part of our history,” Richardson said. “It’s important to acknowledge not only to the good things but the uncomfortable things. People lost their lives for hatred, and that’s something that our country really needs to deal with, and think about, and also acknowledging those lives and the time period. We’re not going to improve our present or our future if we don’t accurately remember and learn our past.”

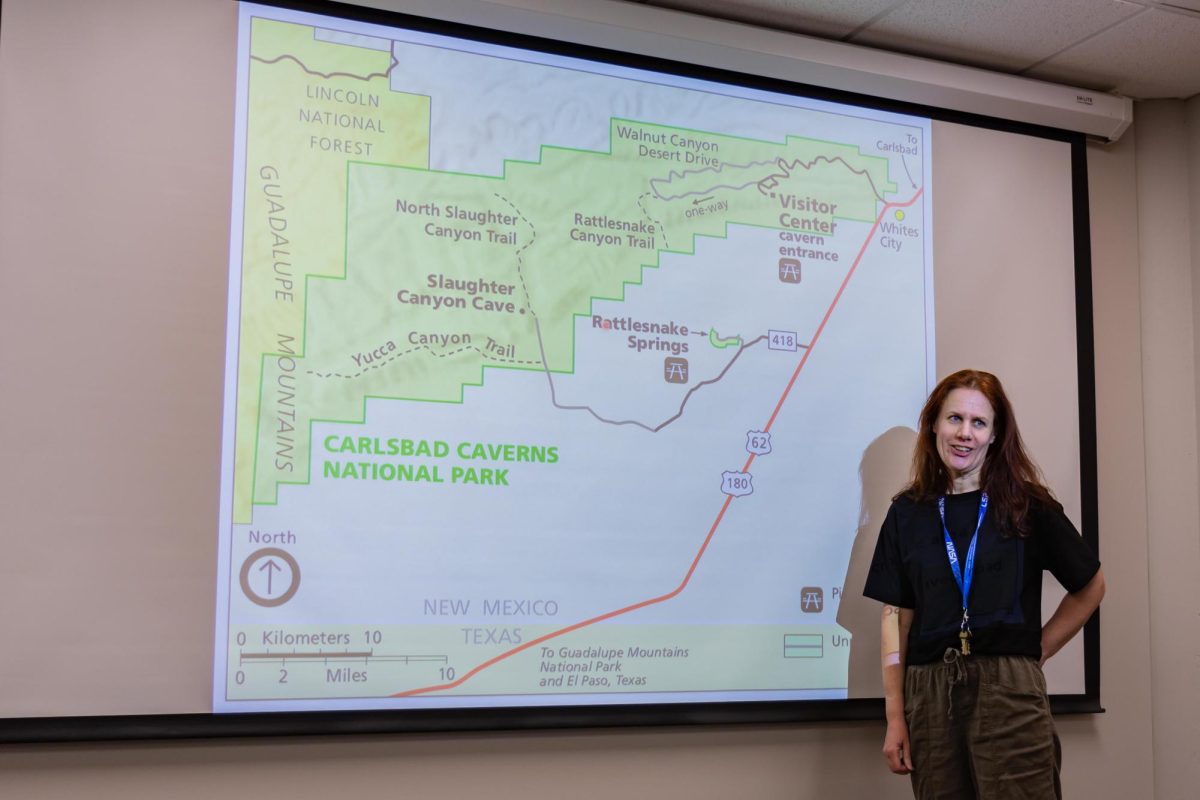

According to the Equal Justice Initiative’s website, the memorial consists of hundreds of six foot, corten steel monuments aligned in a structure that sits above the city of Montgomery. In addition, a monument for every county where a lynching has taken place will be available to be claimed by citizens of the county and installed locally. The museum will be located near the site of what was once one of the most prominent slave markets in the United States.

When Oprah Winfrey traveled to Alabama in order to work on a story for “60 Minutes” about the Peace and Justice Center, she took a detour to Abbeville to visit the grave of Recy Taylor.

As Winfrey mentioned in her Golden Globes speech, Taylor was abducted and raped by six white men in 1944 while walking home from church. Ignoring the death threats of her attackers, she informed the authorities of the incident; however, her case never saw a trial.

In 2010, Danielle McGuire published “At the Dark End of the Street,” a book that contained Taylor’s story among others. The following year, the Alabama legislature passed a resolution apologizing for the mishandling of the case. Though Taylor passed away in 2017, her story is now garnering even more attention.

“Recy Taylor’s story isn’t new — it’s a really old story,” said Cierra Roberson, a senior majoring in African American studies. “Unfortunately, a lot of people do not know about it. So, being that it is Oprah — when Oprah says something, everybody wants to go find out what Oprah’s talking about. I was happy that she brought attentions to it because it made people go and Google and go and read books to find out who Recy Taylor was. So, influence always helps amplify a subject, and it was an important thing to be talked about.”

However, there is concern that this newfound publicity could take unwanted turns.

“It has its pros and its cons,” Smiley said. “Like I said, like awareness — more people know about it, like Oprah. And everybody listens to Oprah, so that’s amazing. But you also always worry about people commercializing and trying to capitalize off of black pain and black history. I’m happy she came, though.”

Students offered their opinions on why the stories of black women like Taylor have become overshadowed by other pieces of the Civil Rights Movement.

“We like to focus on the men of the era,” Roberson said. “So, black women, during the civil rights movement especially, were doing a lot of the background work — a lot of the work that brought forth these marches and the march on Washington and things like that. So, it’s easy to put her on the backburner when the men are doing most of the talking anyway.”

Richardson had a similar viewpoint.

“You have to look at who’s writing the history, who’s telling the history and their perspectives,” Richardson said. “Do they want to tell the full story yet or not? Is that beneficial, or should there be a consistent narrative hidden for a while? But, then it gets lost.”

Overall, Green expects the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, The Legacy Museum and the new publicity surrounding Taylor’s story to eventually have a positive impact on those who are not as active in the fight for equality at present.

“It’s usually something personal — something that [those who are currently inactive] read, someone in their local, daily interactions usually causes someone to become more involved and more active,” Green said. “I think by having Oprah and by having other individuals and the creation of the memorials, it might not be tomorrow, it might be five years, 10 years from now, but they’ll remember like ‘Oh wait, I do remember this happening,’ and they will know where the resources will be.”

Some students expressed their desire for other students to experience the memorials and museums.

“For African Americans and even people throughout the diaspora, I think it’s important to go see [The Peace and Justice Center] because it’s a part of who we are, and how we’ve come to this country, and how were viewed in this country,” Smiley said. “And for everyone else, in general, it’s history — it’s unavoidable history. I think for you not to acknowledge it means that you have an apathy towards it instead of saying like, ‘Oh my god, this happened. This is awful.’ We have a museum now, but let’s also talk about what we’re going to do for black communities and communities of color who are effected by racism and racial terror so that it can’t happen again.”

Richardson thought along similar lines.

“I really encourage people to go to see the lynching memorial and the museum,” Richardson said. “It’s not just a black history type of place. I encourage everyone to go, especially as Alabama is working to add more pieces to the history of Alabama conversation , people going and supporting is absolutely the way to go.”