“With liberty and justice for all.” Every day, most elementary and middle school children stand up and recite these words, hands over hearts. However, history has proven them to be a false promise for some Americans.

For three of the nine “Scottsboro Boys,” a group of black men falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931 on a train in northeast Alabama, this promise was fulfilled about 80 years too late. All but the youngest, Roy Wright, were convicted by all-white juries, even in the face of evidence proving their innocence.

(See also “Scottsboro Boys officially pardoned“)

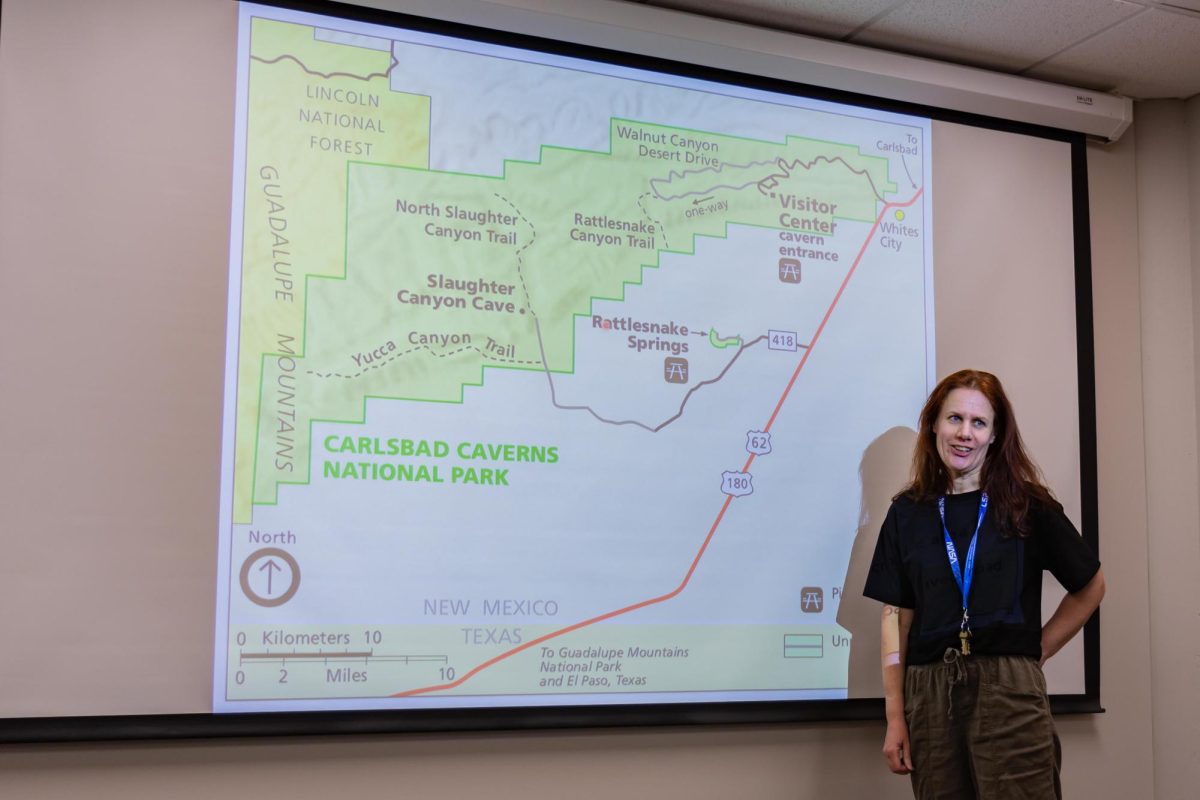

An exhibit of the Fred Hiroshige photographs of the Scottsboro Boys will be on display at the Paul R. Jones Gallery until Feb. 21. There will be a reception Friday from 5 to 7:30 p.m., featuring a talk by Dan T. Carter, Author of “Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South.”

Haywood Patterson, Charlie Weems and Andy Wright were finally posthumously pardoned in late 2013 after living their entire lives under the stigma of a crime they did not commit.

John Miller, assistant director of New College, worked on the committee that petitioned for the pardons.

“I grew up in Alabama,” Miller said. “This is something that I’ve known about. The potential to do something to help change the perception of outsiders of Alabama and the opportunity to lend some measure of justice to these guys’ memories and to potentially ease the minds of their families. It was just something that was the right thing to do.”

The state eventually dropped charges against five Scottsboro Boys, and then-Gov. George Wallace pardoned a sixth, Clarence Norris, in 1976. However, unwarranted felony charges tainted the records of Patterson, Weems and Wright up until the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles unanimously voted to grant them full and unconditional pardons in November 2013.

(See also “Students work to uncover facts about legendary civil rights trial“)

“Posthumous pardons are not common,” Miller said. “They are a relatively recent phenomenon, so the idea of a posthumous pardon is part of the reason that it took this long. The other issue is the last of the Scottsboro Boys was released from prison in 1950. So, to an extent, the case fell out of public imagination.”

Posthumous pardons aren’t usually legal in Alabama. To combat this obstacle, Miller and the other committee members proposed legislation allowing posthumous pardons for individuals charged 80 or more years ago for certain felonies if racial prejudice is believed to have influenced the conviction.

Backed by several historians, civil rights attorneys and government officials, including Sen. Robert Orr, the law passed in April 2013, paving the way for the pardons to be granted in November.

“This is about trying to give the state the opportunity to do something right after something wrong happened,” Miller said. “It’s also about [pointing] out that the justice system can be improved and about clearing the names of these folks in history. People can make the argument that this is largely symbolic and it doesn’t have any actual effect, but I would disagree with that because I think that there are important community-level effects, state-level effects and public policy effects that come out of issuing these pardons.”

More than 80 years have passed since the Scottsboro Boys’ wrongful convictions, but to this day, many feel that racism still permeates the United States’ criminal justice system. This racism can take the form of personal prejudices, but it can also be systematic social inequality upheld by societal institutions, otherwise known as institutionalized racism.

(See also “The Final Barrier: 50 years later, segregation still exists“)

“I think the criminal justice system is somewhere between individualized and institutionalized racism,” said Ebony Johnson, an instructor in the criminal justice department. “You have individual acts of racism that exist on behalf of police officers, judges and prosecutors, and sometimes it’s unintentional and unconscious. When institutionalized, racism is embedded in the day-to-day practices of social institutions such as schools, businesses and the criminal justice system.”

According to a 2005 study conducted by the Sentencing Project, young black and Latino males are more likely to receive harsher sentences than white males for committing similar crimes.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, 65 percent of murders in Alabama involve black victims, but 80 percent of death row inmates in Alabama were sentenced for killing a white victim. While six percent of murders in Alabama involve black defendants and white victims, over 60 percent of black death row inmates were convicted of killing a white person.

The Equal Justice Initiative also states that although 27 percent of Alabama’s total population is black, blacks constitute 63 percent of the state’s prison population, and only one of 42 elected district attorneys in the state is black.

However, because people tend to think of racism as overt acts and prejudices rather than subtle systematic inequalities, not everyone realizes the full extent to which racism still exists, Johnson said.

“Research shows that racism can be conscious or unconscious, intentional or unintentional,” Johnson said. “Individuals working within these institutions may or may not be aware of the policies’ existence and impact. In essence, modern racism is more subtle and indirect and operates outside of our conscious awareness. Even the most well-intentioned people perform racist acts, and they don’t realize it.”

The war on drugs also exemplifies institutionalized racism, Johnson said. According to the Seattle Medium, blacks represent 12 percent of the U.S. population, but they make up 62 percent of incarcerated drug offenders. The Seattle Medium also states black men are incarcerated for drug charges 13 times more often than white men.

“[Racism in the criminal justice system] has created a lack of trust between minority groups and the criminal justice system,” Johnson said. “Furthermore, it has created a sense of hopelessness within [minority] communities. The sentencing disparities that we see related to the war on drugs have become a war on families. As a result, millions of mothers and fathers have not been able to contribute to their communities.”

While statistics show that our justice system tends to work in favor of whites, the system’s unequal treatment of minorities can be attributed to more than just blatant racism, Miller said.

“I think that there are issues [in our justice system] that are related to racism, but I also think that part of this is wealth-related,” Miller said. “People who can afford criminal defense by attorneys who specialize in given areas of criminal defense law are more likely to be treated favorably by the judicial system than those who get appointed councilmen.”

According to a study by the U.S. Census from 2007-2011, 26 percent of blacks and 16 to 26 percent of Latinos fall below the national poverty level, compared to just 12 percent of whites. Higher poverty rates among minority groups prevents many minority defendants from accessing specialized criminal defense attorneys who could help them achieve more lenient punishments.

Additionally, district attorneys and appellate court judges are elected for office in Alabama, which can provide an incentive for them to pursue greater punishments for criminals, Miller said.

“The only way to win an election [is] to show that you are tough on crime, and the only way to show that you are tough on crime is to try to achieve the harshest possible sentences you can on criminals,” Miller said. “The system is tilted in favor of getting the harshest possible sentences. It’s tilted in such a way that people who can afford the best possible defence achieve [more lenient] sentences.”

Both individualized prejudice and the uneven distribution of wealth among minority groups can contribute to the phenomenon of minority groups receiving harsher sentences, Miller said.

“There are cases in which the individual prejudices of a given juror can affect the operation of a jury,” Miller said. “If you have that as a factor, and if you have as a compounding factor the influence of access to legal resources, then what you’re gonna get is basically an amplification of that. So these things are going to tend to react with each other to make things more severe.”

Miller said he hopes the Scottsboro pardons will increase awareness of the prejudices and injustices that influence our justice system, rather than provide an excuse for anyone to deny these prejudices’ existence.

“One of the criticisms of efforts like these is that they are a feel good pat on the pack for a state like Alabama that has a very fraught history with racism,” Miller said. “But that’s certainly not the intent that we entered into this with. The intent that we entered into this with was to start a community dialogue about the impact of things like racial prejudice on outcomes in trials. I hope that nobody looks at this and thinks, ‘Well we can wipe our hands of that. Racism is over.’ I think that that would be the wrong conclusion to draw from this.”

Although pardoning the Scottsboro Boys can’t make up for what happened to them, the pardons will hopefully provide an opportunity for the state to move forward, Miller said.

“I don’t think you can make up for something like this,” Miller said. “If anybody starts with the impression that the purpose of the pardons is to make up for the past, then I think that that’s an inaccurate starting point. You can’t undo a wrong in history. But that doesn’t’ mean that you shouldn’t do the right thing when the opportunity presents itself.”