1974 Alabama Basketball: Breaking barriers with good people

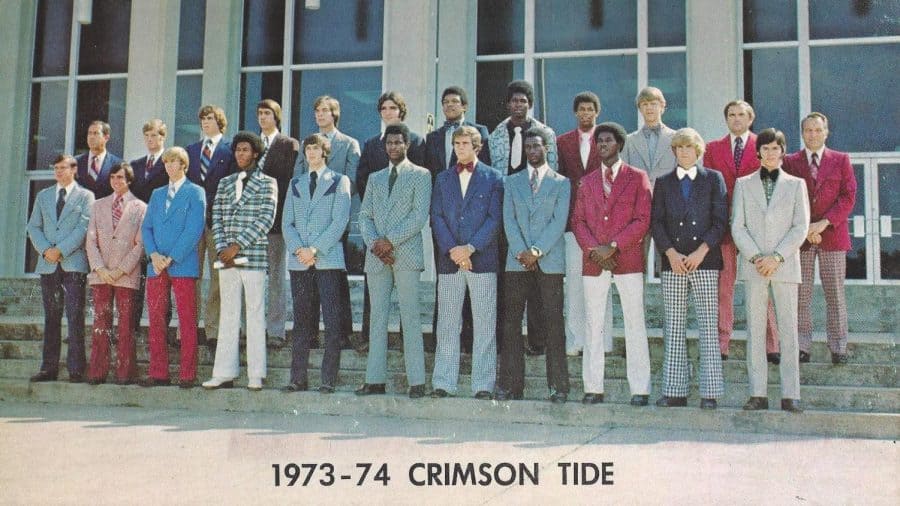

The 1973-74 Alabama men’s basketball team photo.

February 2, 2023

The University of Alabama men’s basketball program has a storied history.

From head coach Wimp Sanderson’s SEC Tournament three-peat in the 1980s and ’90s, to head coach Mark Gottfried’s Elite Eight in 2004, or the program’s return to prominence under current head coach Nate Oats, much of Alabama’s success on the hardwood can be traced back to head coach C.M. Newton, who came to Alabama in 1968.

Newton was 38 years old when he arrived at the Capstone to lead Alabama’s basketball team. Coming from Lexington, Kentucky, he was relatively unknown among the national coaching ranks.

“He was a gentlemen in every regard and every moment that I ever knew him,” said Ben Shurett, a manager and then graduate assistant for the Alabama basketball team from 1969-74. “I never really saw him change. He was always that person who was an outstanding tactician, and outstanding coach, a good recruiter. A good person who valued all people.”

In Newton’s first year in 1968, the Crimson Tide suffered a 4-20 regular season. Following this, Newton recruited Wendell Hudson, who became the first Black scholarship athlete in the University’s history.

Over the next few seasons, Newton recruited more Black players and won more games. Alabama improved its win total over the next five seasons under Newton, winning eight games in 1970, 10 in 1971, 18 in 1972 and 22 in 1973.

This led to the 1974 team, the team that sent shockwaves throughout the Southeast.

The team started the season with a 5-1 record, and next on the schedule was the eighth-ranked University of Louisville Cardinals on Dec. 28, 1973. As the game began, Newton sent his starting five onto the floor.

Ray Odums, T.R. Dunn, Charles Cleveland, Charles ‘Boonie’ Russell and Leon Douglas. These five players — all of whom were Black — took the court.

These five men made history on Dec. 28, 1973, becoming the first all-Black starting five in the history of the Southeastern Conference.

Sanderson, who was an assistant coach under Newton at the time before taking over the program in 1981, said that there weren’t any previous discussions from the coaching staff about the fact that this lineup was all-Black.

“We didn’t talk about it. We didn’t even think about it,” Sanderson said. “We played the game. We had however many kids we had, some Black, some white, we started who we thought was the best team to start.”

Odums, who was a senior guard on the team, said that it wasn’t something the players talked about either.

“We just figured Coach [Newton] put the best players for us available at that time,” Odums said. “Our five was all-Black, but we didn’t dwell on that point. We just felt that we were out there playing, trying to do a good job to win games for ourselves and our university.”

Douglas, who was just a sophomore on that team, had a bit of a different mindset.

“I was aware, because I had been looking forward to that,” Douglas said.

Alabama won that game against Louisville by a final score of 65-55 and went on to share the SEC regular season championship with Vanderbilt. The team finished the season with a 22-4 record and the SEC championship was the first won by the Crimson Tide since 1956.

As this team was formed over Newton’s early tenure, Sanderson, the lead recruiter on the staff, wanted his players to meet a few criteria, none of which were race related.

“We recruited good people who were good students and good athletes,” Sanderson said. “That’s what we looked for. We had a certain standard. … We got good players. We didn’t worry about whether they were Black or white.”

Douglas, who went on to be the No. 4 overall pick in the 1976 NBA Draft, said that other schools used race as a recruiting pitch against Alabama.

“Everyone said that Alabama would never start five Blacks,” Douglas said. “When there was a recruitment war going on, the people that recruited against Alabama would always say, ‘You know, Alabama’s never going to start all you guys.’”

The entire starting five was made up of players from Alabama, and Douglas said that making the decision to stay home was an easy one for all of them.

“We were all from Alabama and we recruited each other. We recruited each other with the standpoint of if we all went to the University, we could not only change it but set a standard,” Douglas said. “We decided to stay in the state and make a difference.”

Once this collection of players got on campus together, an unbreakable bond was formed.

“When we got on the court, we were all for one and one for all,” Odums said.

“We’re still friends. We’re like brothers,” Douglas said. “Even to this day we call each other. There’s a brotherhood there. That’s one of the reasons that we were able to do the things that we did. … We were competing and playing with a purpose.”

Even for the white players on the team, like sixth man Johnny Dill, the fellowship formed by that team was special.

“We got along as teammates very well,” Dill said. “They were my friends. We wanted to win basketball games. [The coaches] treated us with great respect. In four years with them they never belittled us.”

Shurett, who witnessed Newton’s teams closer than anyone not playing on the court, felt that the people are what brought these teams as close as possible.

“I think it’s a real testament to the people that were on all of those teams,” Shurett said. “C.M. [Newton] never said to us, ‘Hey, we’re going to have a Black guy on the team.’ It was a team; it was our team. I was very blessed that the people on that team let me be on that team. I was a manager, but I was all in. They treated me like I was a player, and I was emotionally invested in that.”

Shurett said that the togetherness formed by teams with great people is one that transcends all divides.

“Friendships are not based on success on the field or on the court,” Shurett said. “You certainly might find that the very best players might be best friends with the third-team linebacker or a student manager. That’s not designed by race. That’s people who are drawn to each other. … That dynamic plays out on every team with good people. What I remember most is our people were good people.”

The 1974 team laid a foundation, and paved the way for more growth as the years went by. Now in 2023, all 11 scholarship men’s basketball players at the University are Black, a testament to the barriers broken by Newton, his staff and his players.

So, even now, as Alabama basketball fans are enjoying a Crimson Tide renaissance on the 94-foot floor of Coleman Coliseum, remember to look to the rafters and reflect on the teams, wins, championships, and most importantly, people that came before.

“People have a tendency to forget the past, but there’s no present without the past,” Douglas said.