Opinion | UA Owes More to Students and Our Organizations

September 7, 2022

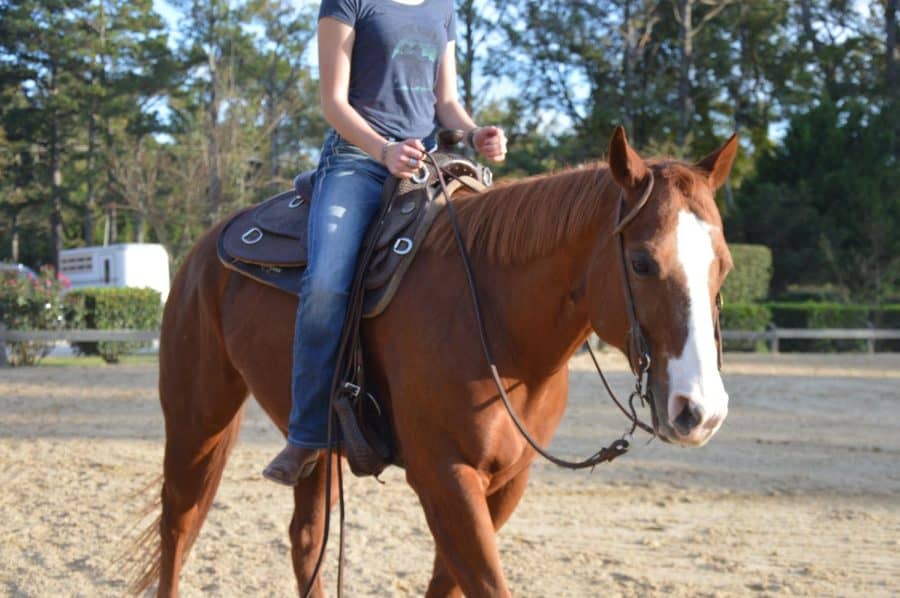

In October 2021, the University of Alabama Equestrian Club created a GoFundMe campaign to stay afloat after being demoted from a varsity sport to a club sport in March 2020 — despite 22,000 petition signatures encouraging the University to reverse its decision. Almost a year later, the club’s survival still relies on the generosity of donations.

With the plethora of resources which it constantly flaunts, The University of Alabama has no excuse for letting a student organization fall by the wayside and resort to crowdfunding and high dues to exist.

Abigayle Kneebone is a senior studying political science and criminal justice. She is the president of the Equestrian Club, and has expressed her discontent with how the University neglects organizations like hers.

“We do get some funding from the University for the club, but … it is not nearly enough, especially with this kind of sport,” Kneebone said. “It’s much more difficult to keep a club of this nature afloat with the amount of funding we get because a lot of our costs are ongoing and not a one-time flat rate type of thing.”

Kneebone noted how the club’s two horses, Vinnie and JJ, need to be fed and boarded in addition to receiving annual vet care, dentistry and emergency work on their hooves.

“Horses aren’t cheap and they aren’t something we can practice without,” Kneebone said.

The Equestrian Club must also cover the costs associated with competing, including “renewal fees, individual member fees, horse rental costs at shows, entry fees, associated travel costs [and] costs associated with show clothing” — costs which Kneebone expects will increase in the upcoming season.

With a lack of sufficient institutional funding from the University, the Equestrian Club is forced to push these costs onto its members. Dues increased from $375 in fall 2021 to $400 in spring 2022.

“More than likely, we will have to hike our dues in response to the increase of our show costs [and] returning members who had a hard time financially meeting the costs last semester may end up not being able to participate because they cannot afford it anymore,” Kneebone said.

As Kneebone indicates, such overwhelming costs limit the accessibility of these clubs and take an inordinate toll on members from less wealthy backgrounds. Unfortunately, the University is allowing organizations like Kneebone’s to go underfunded, while simultaneously demonstrating that we have more than enough resources on campus to prevent such a situation from happening.

Nick Saban, the head coach of the Crimson Tide football team, makes $11.7 million annually on an eight-year contract totalling $93.6 million. Not only does this make him the highest paid coach in college football, but also the highest paid state employee in all of Alabama. With this in mind, it is not hard to understand why Kneebone says that “the ‘Where Legends Are Made’ slogan only feels like it applies to the talent on the football field.”

The mistreatment of the Equestrian Club by the University is worthy of discussion on its own. However, this issue is a microcosm of a much more pervasive and insidious reality on our campus: an inequitable wealth distribution that sees students and faculty lose out while administrators and trustees watch their pockets overflow.

Point in case, a recent Crimson White article highlighted glaring examples of opulent spending and greed which the University pursues instead of contributing to the actual wants and needs of its students – the very people the institution was supposedly founded to serve.

The University loves to pour money into bloated six-figure salaries for administrators who are far-removed from the day-to-day experiences of student life. For example, President Stuart Bell raked in “over $823,000 in 2021, up from a modest 2020 salary of just over $815,000.”

UA also recently spent $4 million to renovate the so-called “Trustee Playhouse” – a building originally intended for student use which now only serves as a function hall for Alabama’s uber-wealthy.

Compare these massive sums of money to the relatively meager SGA Financial Affairs Committee Funding budget of $100,000 per semester which must be painstakingly allocated across all student organizations on campus. Because of this, the maximum amount of funding available to eligible student organizations is capped at $7,500 per fiscal year.

Of course, this figure is arbitrary, and it does not necessarily reflect the actual needs of the average student organization. Some may never need to access that maximum amount of funding, while others — like the Equestrian Club — could benefit immensely from greater institutional financial support due to the cost-intensive nature of their clubs.

One might argue that an organization as expensive as the Equestrian Club should not exist. In a case where such a club’s existence drags funding away from other campus resources, this may very well be true, but that is not the case here.

What Kneebone and others are dealing with is an unjustifiable hierarchy in which administrative wealth is being prioritized over student life.

There is a vast coffer full of funds which would be more than sufficient to support hundreds of equestrian clubs at the University. The problem is that it is securely guarded by privileged elites who would much rather renovate an esoteric-function hall than create an environment where students can freely explore their extracurricular interests and pursue meaningful interaction with their peers. For reference, 553 of UA’s 576 student organizations could have gained maximum funding with the money used to update the “Trustee Playhouse.”

So how does one justify such frivolous spending that never trickles down to the students and faculty who actually breathe life into the University? Who can explain why the booze bills from Board of Trustees game day parties are worth more than four campus workers’ annual salaries combined? And why should the Equestrian Club struggle to stay afloat while the University’s endowment surpasses $1 billion? On top of all of this, how are students actually paying more tuition now than ever before?

The University of Alabama may claim to value its students above all else, yet time and time again, it fails to put its money where its mouth is. With board members and administrators swimming in more money than they know what to do with, it is time to demand that our priorities are met, that our organizations are properly funded, and that the ever-rising price tag on our education is actually worth a damn.