Sororities Can Benefit from One-Party Recording Laws

August 28, 2022

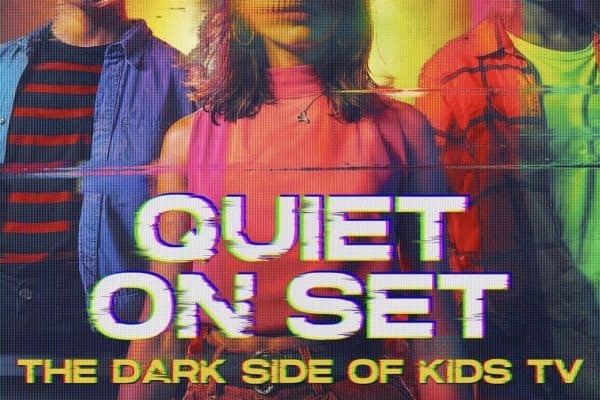

During the recent panhellenic sorority recruitment process at The University of Alabama, rumors were sparked about the possibility of potential new members secretly recording their conversations for a new documentary.

Last year, “Bama Rush Tok” went viral as potential new sorority members unveiled their outfits, accessories and advice in preparation for recruitment week. This TikTok trend amassed over 1 billion views last year, and has continued to go viral.

This trend has garnered the attention of both Vice Studios and HBO Max. The two large digital media corporations are creating a Bama Rush documentary, which Director Rachel Fleit describes as a “thoughtful and passionate portrayal of young women.” However, many active sorority members are concerned about the publicity that such a documentary would generate.

For this reason, prospective members and sorority alumni have been skeptical about the possible involvement of recording devices throughout the recruitment process. Most recruitment week activities occur behind closed doors and are purposefully not publicized.

The UA Panhellenic Association prohibits the recording and sharing of any recruitment party events and chapter videos. Potential new members who are accused of recording in these instances may be dismissed from participation in recruitment.

While a representative from HBO denied accusations of undercover recordings during the recruitment process, this incident brings up a broader topic of Alabama’s privacy laws. In organizations without guidelines to prohibit recordings, it is often permissible for one party to record a conversation that they are a member of.

Secret audio and video recordings initially appear to be a violation of privacy, but this is not always the case. Alabama is a one-party consent state; in order to record a private conversation, only one party in the conversation must give consent to record, and this party may be the one choosing to record.

If an individual wants to record a conversation they take part in, they are legally allowed to do so. In fact, one-party consent laws are useful in a plethora of situations. Recordings are admissible in a court of law, and can therefore disclose language and actions that may aid in an individual’s legal battles.

For example, one-party consent recordings are frequently used in cases of divorce and custody battles. These recordings can become evidence of abuse in a relationship and can aid in a court’s decision making process.

In the Alabama Supreme Court case of Stinson v. Larson, Jodie Larson was able to retain custody of her children because of one-party consent laws. Since she had full custody of her children, she was able to record conversations between her children and their father, Michael Stinson. This evidence proved that Stinson had violated court-mandated communication guidelines. Without this recording, the outcome of this decision may have been vastly different.

In general, recordings under one-party consent laws can provide substantial evidence in a court case and refute false information that may have been previously provided. From small personal conversations to larger harassment claims, an involved party has the potential to document these interactions.

Alabama’s one-party consent laws can especially be useful to students participating in Greek life at The University of Alabama. Many individuals automatically associate Greek organizations with historic hazing practices, which can result in physical injury and severe mental distress for members.

More flexible recording policies show the public that Greek organizations truly care about the well-being of their members, which can attract more potential new members.

Greek organizations at the University should acknowledge one-party recording laws and the positive impacts that they can have on their own organizations. Members of Greek life should not be afraid to risk their membership when documenting instances of hazing and threatening behaviors.

Sororities have their own secret traditions that are not harmful and therefore do not need to be recorded. However, strict limitations on recording can make potential new members feel silenced when involved in an unsafe situation. Other active members may consider hazing to be permissible if there is no chance that evidence can be recorded.

The University of Alabama has condemned reports of unauthorized filming. Media recordings are not authorized in sorority houses, as the University states that many members may also be minors. The ban of recordings can hurt minors though, as they have limited protection if placed in a hazing situation.

Previous documentaries on The University of Alabama’s fraternities have exposed hazing and other dangerous practices. The effort to protect minors should include their ability to document and protect themselves from potential harm. This benefits everyone involved and creates a better Greek system across campus.

The UA Panhellenic Association should further re-evaluate their media recording policies to find a balance between tradition and creating a safe environment for all members involved. Acknowledgement of one-party consent laws can create an environment of transparency that protects members and can give Alabama Greek life a more positive reputation.

Note: While the state of Alabama has instituted one-party consent laws, it is important to consult professional legal advice before attempting to use such recordings in a court of law.