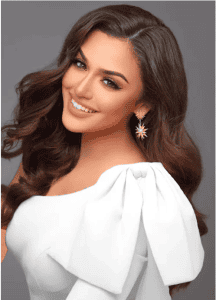

Women find community in STEM fields at UA

April 17, 2022

In the fall of her freshman year, Sarah Holdrup, a senior majoring in environmental engineering, received a lower grade than her male lab partner, despite turning in the same lab report. When she met with the professor to question the grade, the professor told her this was something she should expect in a workforce where she would be paid less and be listened to less than her male colleagues.

At The University of Alabama, women make up 20% of the faculty in the College of Engineering and 27% of the faculty in Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

Holdrup didn’t let this experience stop her from pursuing her degree, and that spring, she joined the University’s chapter of the Society of Women Engineers. She is now the president of the organization and recently received the Guiding Star award for her significant contributions to the section and the UA campus.

The organization connected Holdrup with other female engineering majors who shared similar experiences, recommended professors and classes, and encouraged her through challenging classes.

Alina Iliescu, a senior majoring in aerospace engineering, also found a community of women in UA Women in Aeronautics and Astronautics, a professional development organization and a social club that builds a community within the aerospace discipline.

Iliescu said she experienced impostor syndrome, a feeling of not belonging, from being in these difficult classes as a woman.

“It was nice having a little support group with people that are going through the same thing,” Iliescu said. “The social meetings really help the girls get to know each other and make friends within aerospace, because like I said, it’s kind of hard meeting other women in aerospace.”

Katie O’Harra, an assistant professor of chemical engineering in the Honors College, said she recognized this gender imbalance during her undergraduate classes at the University from 2013 to 2017. In her four years, she only had two female professors in her science, technology, engineering and mathematics classes.

This bothered her because she knew it didn’t reflect the changing engineering student gender demographics. This thought motivated her to teach in graduate school and become a mentor to nine undergraduate chemical engineering majors, eight of whom were women.

“If you can go through your entire four-year curriculum and not experience a different perspective or lived experience, that can be kind of frustrating, especially if you want to envision yourself in that role,” O’Harra said.

Now, O’Harra leads the Engineering Positive and Intentional Change Scholars Program. Through the four-year curriculum, honors engineering students learn about the broader impacts of engineering on social justice and the environment.

“Just because you don’t necessarily see yourself represented there yet doesn’t mean that’s not the place for you,” O’Harra said. “Sometimes you might be the only woman in the room, but you’re there for a reason. You should be there to contribute your unique perspective and experiences that only you can bring to the table.”

As the first Black woman in Alabama to earn a doctorate in physics, Shelia Nash-Stevenson often remembers being the only woman in her workroom.

Nash-Stevenson has worked at Marshall Space Flight Center for over 30 years and currently works as a science projects manager. She now works under the first female director of Marshall Space Flight Center, UA alumna Jody Singer.

“The glass ceiling has been broken,” Nash-Stevenson said. “There’s more and more females coming up that are able to take on those responsibilities that have been traditionally male responsibilities. Females are doing a great job at Marshall and at NASA.”

According to the U.S. Census, since 1970, the share of women in the science, technology, engineering and math workforces has increased from 8% to 27%.

Jules Bates, a junior majoring in chemical engineering, said she believes the work of these women has impacted her academic journey as a woman in STEM.

“The fact that I’m not really able to think of anything that has set me back and set me apart from my male peers, it really speaks volumes to the work that has already been put in to make engineering and especially chemical engineering more equal and have more equal opportunities,” Bates said.

Bates recently received the Goldwater Scholarship for her research on using stem cells to treat epilepsy.

“When I got the Goldwater, this was after I had already been researching for two years, it meant a lot because it was a huge payoff from the work I have been doing,” Bates said. “It just gave me some inspiration that I am following the goals that I set for myself and I am on the right track.”

Nash-Stevenson said she encourages women in STEM to connect with other women, stick together and make sure they succeed.

“When I was in school, there were very few females in STEM fields. Those that were, we hung out together, studied together and encouraged each other because we had the same capabilities — and sometimes more — than our male counterparts,” Nash-Stevenson said. “People will tell you you can’t do it, but it’s not their decision.”

Questions? Email the culture desk at [email protected].

![NEWS | Homecoming Week kicked off on Sunday with the Roll Tide Run and the Homecoming Kick-Off.

The Homecoming committee hosted a Roll Tide Run 5K that started from the Quad, went around the Student Recreation Center all the way down the row of fraternity houses, and then ended at the Student Center.

“My goal for Homecoming this year is to make sure that everybody feels welcome,” said Anthony Bellman, executive director of Homecoming. “I know a lot of our events are mainly focused towards fraternities [and] sororities, so I’ll open that up to the general student population.”

📸 CW / Braxton Bevis

🖊️ CW / J. Calister Clemons and Sujith Mareddy

Read the full story at the link in our bio.

#theuniversityofalabama #universityofalabama #alabama #uofa #ua #crimsontide #rolltide #tuscaloosa #tuscaloosaalabama #alabama #bama](https://thecrimsonwhite.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)