As UA grows, Black enrollment lags

October 20, 2021

It’s hard not to notice that The University of Alabama is growing. Just look at the endless parade of construction projects taking place on campus. Or ask one of the hundreds of students who were supposed to live on campus this fall, until a larger-than-expected incoming class of 7,593 freshmen forced them and the University to make other arrangements.

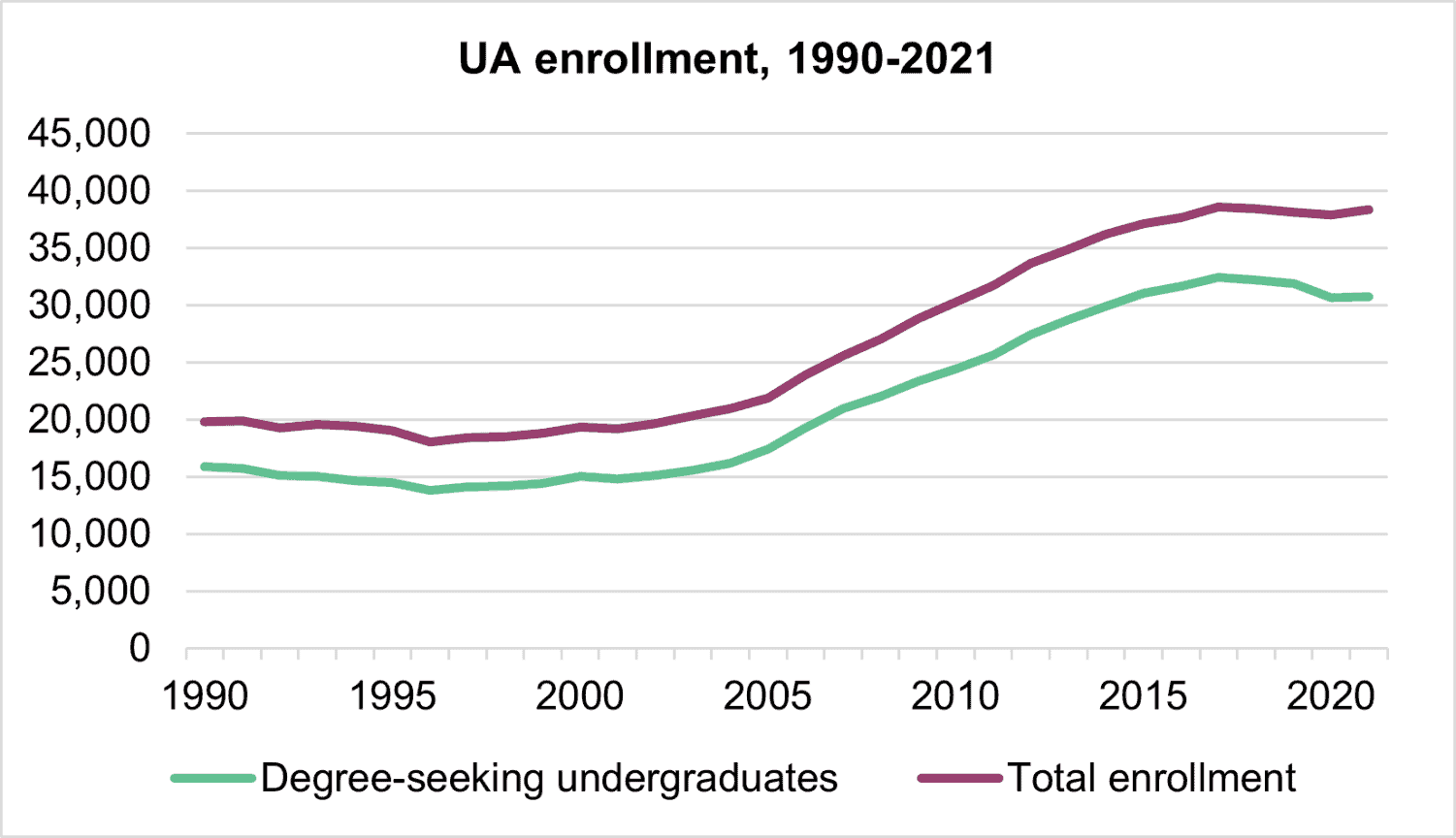

That record-breaking first-year class brought total enrollment to more than 38,000 for the fourth time in the University’s history. The vast majority of UA students — some 30,700 — are undergraduates working toward a four-year degree.

In the past 20 years, the number of degree-seeking undergraduates at the University has more than doubled. Yet the number of Black students in this group has risen by only 47%.

Black students have been underrepresented at the University since its founding in 1831. For more than two-thirds of its history, the University did not admit Black students. It was integrated less than 60 years ago, in 1963, when Gov. George Wallace stood at the door of Foster Auditorium in an unsuccessful last-ditch effort to block the entry of the University’s first two Black undergraduates.

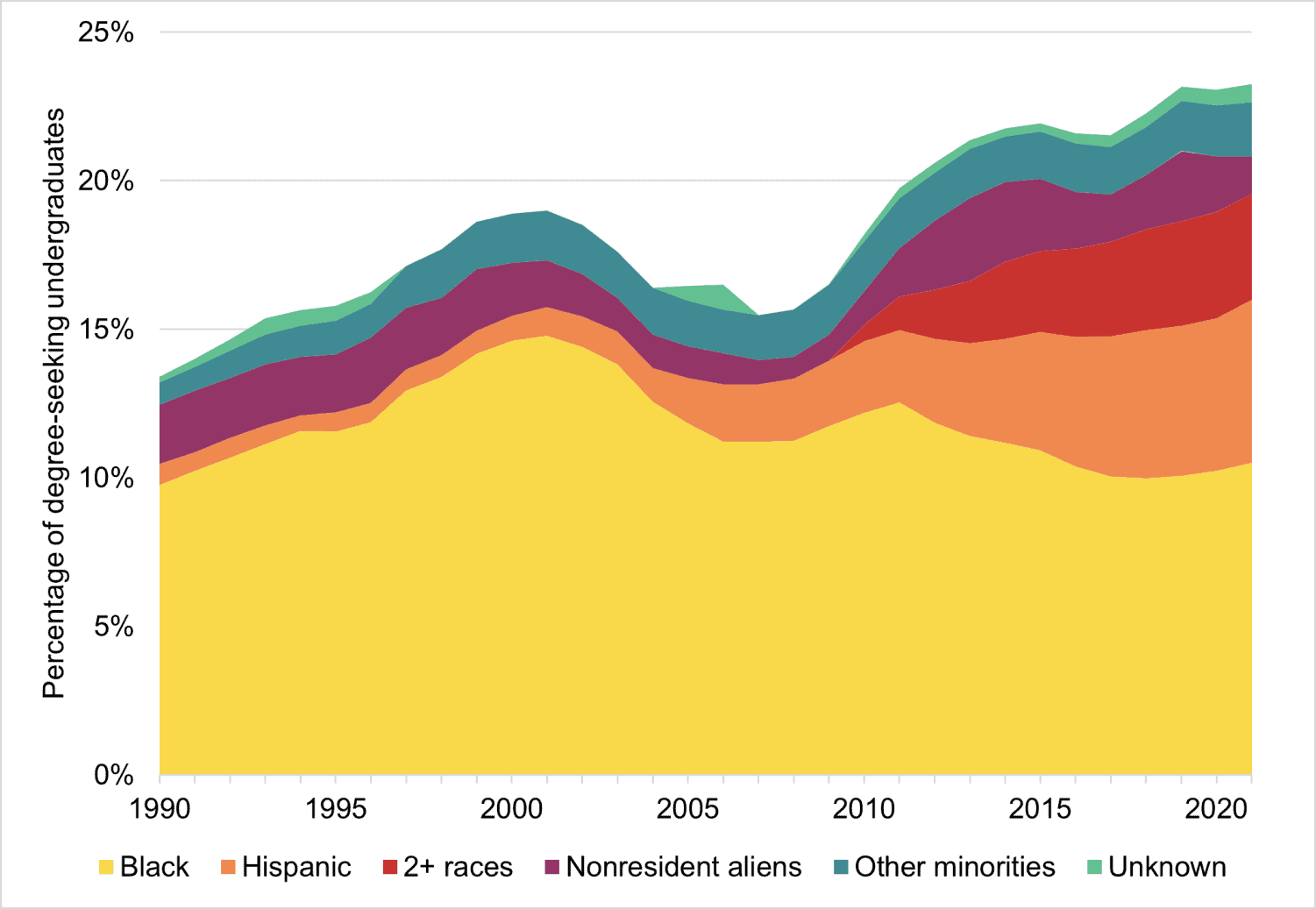

The proportion of Black degree-seeking undergraduates on campus peaked in 2001, at 14.8%. Since then, it has fallen to 10.5%. Throughout the past 20 years, African Americans have accounted for a little more than a quarter of the state’s population.

G. Christine Taylor, the University’s vice president and associate provost for diversity, equity and inclusion, declined to speculate on the reasons for this trend. During her four years at the University, the percentage of Black degree-seeking undergraduates has risen by about half a percentage point.

“I just came and said, ‘Wow, we need to do better,’” Taylor said.

In 2017, the University hired Taylor to lead its newly established Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, which was created in part to “recruit, retain and graduate more diverse students,” according to the division’s website. The following year, the share of Black degree-seeking undergraduates at the University hit a 28-year low. It has increased modestly each year since then.

Gabby Kirk, a freshman majoring in secondary education, said she wasn’t surprised to hear that the share of Black students at the University had gone down in recent decades. She said she has seen Black students gravitate to historically Black colleges and universities as stigmas surrounding these institutions have eroded.

“We were told that HBCUs weren’t as professional and they won’t be seen as serious in the professional world or whatever. So a lot of people went to PWIs [predominantly white institutions], but now I think … people realize, ‘Hey, Howard can have the same credentials as Yale,’” Kirk said.

She said Black students can sometimes feel unsafe at schools like The University of Alabama because of their fraught racial history and relative absence of Black faculty members and administrators. As of last year, 7.6% of faculty members at the University were Black.

“Sometimes the student body has a racist history of behaving this way toward Black students,” Kirk said. “Why would I put myself in this position?”

Matthew McLendon, who has served as the University’s associate vice president and executive director of enrollment management since October 2019, said the question of lagging Black enrollment is a complicated one.

“I think that that’s one of those questions that researchers themselves are looking at, because I think there’s national trends that play into that,” McLendon said.

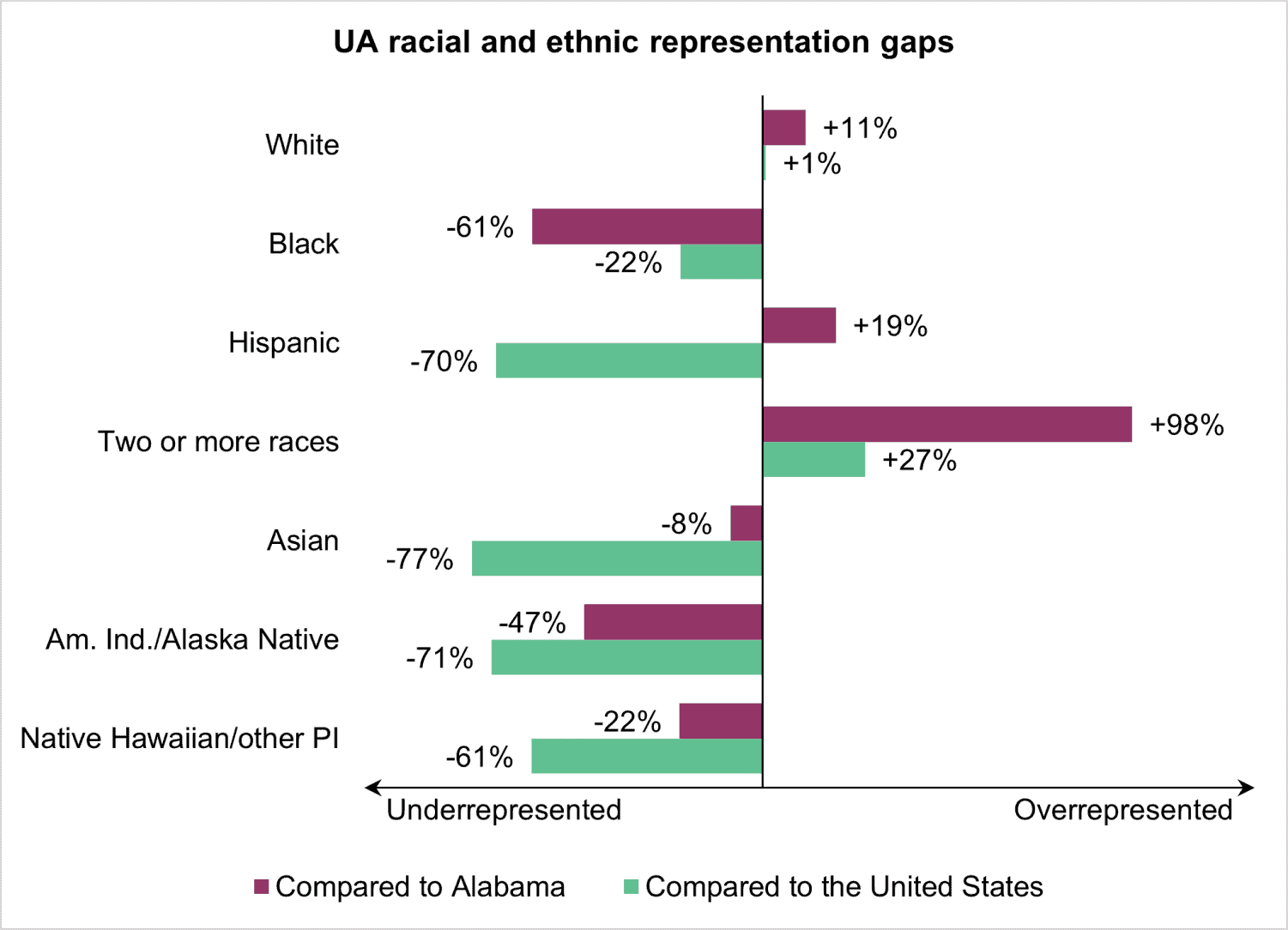

A 2020 report from the Education Trust, a nonprofit focused on improving equity in education, found that between 2000 and 2017, the share of Black students declined at 58% of selective public colleges, including The University of Alabama. According to the report, Black students remain underrepresented at more than 90% of selective public colleges compared to the states where these colleges are located.

To alleviate such disparities, the report’s authors recommend that institutions take a number of steps, including changing recruitment strategies, offering more financial aid to students from underrepresented minorities, improving campus racial climates, and deemphasizing or ignoring standardized test scores in admission decisions.

On the recruitment front, McLendon said his office has collaborated with the Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion to organize events such as the Multicultural Visitation Program, which took place Oct. 10, and Our Bama, an annual event for admitted minority students and their parents. He said the University plans to hire an assistant director for multicultural recruitment this year.

McLendon said financial aid also plays a role in the University’s strategy for diversity, equity and inclusion. He pointed to the University’s participation in the College Board National Recognition Programs, which provide academic honors to underrepresented students based on their scores on the PSAT or Advanced Placement exams.

Students who receive these honors qualify for a scholarship package from the University that includes four years of tuition, one year of on-campus housing and $4,000 in supplemental scholarships.

As for standardized testing, the University stopped requiring SAT and ACT scores for undergraduate admission last year in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it difficult for many students to take either test.

The Education Trust report advocates “a holistic admissions process that incorporates race as a significant factor in [admission] decisions.” The University currently does not consider race or ethnicity in its admission decisions.

Taylor said the University’s diversity initiatives are driven by the idea that everyone benefits from a diverse student body.

“[Diversity] makes for a better educational experience,” Taylor said. “You tend to be more civic-minded. You tend to be more critical thinkers. You tend to be more engaged in your communities.”

She added that interacting with people of different backgrounds is crucial to preparing students for an increasingly heterogeneous and interconnected world.

“This is really about increasing the diversity with the understanding, as supported by research, that there is a value for students who have an opportunity to interact with diversity and inclusion, because the world that you’re going to work in and that you’re going to live in, we already know, is going to be dramatically more diverse and global than what you’re currently experiencing,” Taylor said.

According to a 2017 working paper from the Harvard-based research group Opportunity Insights, a UA student whose parents are in the bottom fifth of incomes has a 25% chance of entering the top fifth as an adult. That puts The University of Alabama at 600th out of 2,137 U.S. colleges.

Taylor said that, in general, the minority students the University hopes to attract don’t suffer from a lack of options.

“Diverse students are going to college. They just may not be choosing to come to Alabama. … It is not as if, if they’re not coming to Alabama, they’re on the side of the road,” she said. “Their choices are not us or a two-year [community college]; their choices are us or Georgia Tech, us or UGA, us or Vanderbilt.”

Kirk said she chose the University because of its football program and because it offered her original major, physiology. She said learning about campus organizations like the Black Student Union and the Black Faculty and Staff Association made her feel better about her choice.

“I’m like, ‘Oh, okay! Look, I see people down here that look like me.’ But I kind of had to go looking for that,” Kirk said.

Caption: Degree-seeking undergraduates, who represent the vast majority of UA students, have more than doubled in number since 2001. Total enrollment data is available online from the UA Office of Institutional Research and Assessment.

![UPDATE | New details have emerged about U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s arrest of doctoral student Alireza Doroudi.

— Yesterday, a University spokesperson confirmed that a doctoral student was arrested by federal immigration authorities, without providing the student’s name, declining to share specific information due to federal privacy laws.

“International students studying at the University are valued members of the campus community, and International Student and Scholar Services is available to assist international students who have questions,” said Alex House, associate director of media relations for the University. “UA has and will continue to follow all immigration laws and cooperate with federal authorities.”

— An employee at the Pickens County Jail confirmed that Doroudi is being held there, adding that the facility typically sends ICE detainees to a detention facility in Louisiana.

— The Department of Homeland Security provided a statement about Doroudi’s arrest:

“ICE HSI [Homeland Security Investigations] made this arrest in accordance with the State Department’s revocation of Doroudi’s student visa. This individual posed significant national security concerns,” a DHS spokesperson said. The statement did not provide details about why it claimed Doroudi posed national security concerns.

— Students for Justice in Palestine at UA, formerly known as Bama Students for Palestine, said in a statement on social media Thursday that it was “outraged” to learn of his detainment and that he "was not involved, nor has he ever been involved in any organizing or protests related to our organization."

This is a developing story and will continue to be updated. Read the updates at the link in our bio.](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/486944895_18492822301025566_6944596333023050206_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=hnp26Pzwsm0Q7kNvgH09W0S&_nc_oc=AdmIBEMuR_aRgaBd00Hlot3E59Vj_4lQyCImLLgp8CLdbxpSmLU25dhU_MO_Zul-qcU&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=Eef0YMIFzxMaiUpFitZOLg&oh=00_AYGXXmlh-QsW5bKnKx6w8LK3Rdz_HpdqlpeEraurXrQNsQ&oe=67F30BB0)