I’ll admit, I took a wrong turn down Old Greensboro Highway on the way to Shelton State and showed up a few minutes late for “Bear Country.” Outside, the usher tried to fill me in.“Bryant’s just saying…” He thought for a moment. “…blah blah blah.”

It was OK, because a little later Bryant said the same thing.

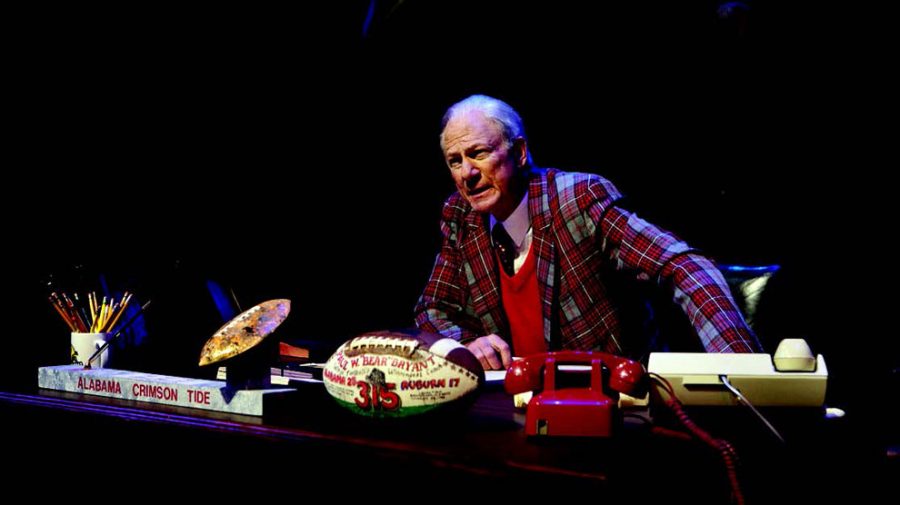

I had missed three or four minutes of nostalgic soliloquy, the old coach’s activity of choice as he packs up to leave his office for the last time. There’s an open bottle of Jack on the desk, and Rodney Clark’s Paul “Bear” Bryant ambles around with the air of a man who has never bothered much with reminiscing.

As his memories unfold on stage – from his first taste of football at his uncle’s radio to his head coach gig with Alabama – playwright Michael Vigilant makes two assumptions: Football is best and Bryant was awesome. They work like narrative Miracle Gro. Why does young Bear want to play football so badly? Duh, it’s football. Why is he always the star player and how exactly does he become head coach? Duh, he’s Bear Bryant.

Old Bear makes grabs at early character development, referencing classism and self-esteem issues, but on stage, Young Bear (Joel Ingram) has all the character of a well-trained golden retriever. He mostly nods as coaches shout locker room clichés or talks football with his token black sidekick. Every conflict, from a leg injury to his father’s death, melts away after a few seconds of get-back-out-there platitude.

But, after all, he is Bear Bryant.

After a bewildering 20 year leap (Bryant’s coaching stints with other schools go entirely unreferenced), Vigilant manages to find a few antagonists – basically, anyone who doesn’t play football. They include attorneys, sports writers and even a slimy lab technician. One columnist writes, “Coach Bryant must be stopped!,” and in another scene Bear goes head-to-head with a genuine, bona-fide, cigar-smokin’, chair-leanin’-back-in racist. These characters are evil simply because they don’t like Bear Bryant and dilute what could be compelling drama with cape-swishing and moustache-twirling.

Not that they stand much of a chance. Somewhere in those 20 years, Bear goes from wide-eyed jock to Dick Tracy. Ingram does his best but he’s not suited for hardboiled. He plays Adult Bear with a perpetual grimace that contorts his face like a lava lamp, knocking down Vigilant’s villains as fast as can set them up with little more than poster slogans and scowls.

Of course, the flashbacks are mere illustrations for Rodney Clark’s monologues. Fortunately, Old Bear is the only piece of Alabama football the show doesn’t pass off as a Sunday morning cartoon. Clark delivers the seasoned hero with subtle distinction and carries a sincerity that manages to cover up most of Vigilant’s schmaltz.

But Vigilant doesn’t seem to know the difference between introspection and ham-handed exposition, and as Act 2 winds on, even Clark starts to sag. Bear’s flashbacks grow shorter, thematically disparate and lose temporal continuity. Eventually they disappear altogether, leaving Old Bear to just rattle off stray anecdotes that slowly congeal into an almost indecipherable pool of cliché.

Perhaps what disappointed me most was that, behind the caricature, I could tell there was a real story, if Vigilant had only bothered to tell it. But in the end, standing ovations came not from college youngsters, but folks who didn’t need the story – folks who lived it. For them, the play was homage to their own memories.

At the very least, we may get a new tradition out of it: Stations of the Cross on Easter, “Bear Country” on A-Day.