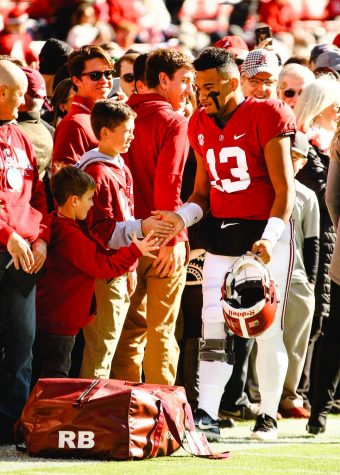

Tagovailoa leaves legacy of family, excellence and selflessness

Alabama quarterback Tua Tagovailoa on Monday announced his intention to enter the NFL Draft. From coaching sorority flag football to a trip to Hawaii to spontaneous jam sessions, he has left The University of Alabama and the lives of the people around him better than he found them.

January 6, 2020

T.J. Simmons didn’t have much to do.

The most grueling part of the wide receiver’s year – Alabama football’s Fourth Quarter program – had just ended, meaning his days, previously filled with intense workouts and the grating, gravelly voice of strength coach Scott Cochran, were now a lot more open.

With spring football still a few weeks away, Simmons was lounging around his dorm room at Bryant Hall one day when Tua Tagovailoa, the team’s early-enrolled five-star freshman quarterback, stopped by to say hello.

After some small talk, the conversation between the two shifted to Tagovailoa’s guitar skills.

“I was like, ‘I gotta hear you play one day,’” Simmons said. “He was like, ‘I’ll be right back.’”

A moment later, the quarterback returned with his guitar and his roommate, fellow freshman Najee Harris. He sat down and played two original songs, including one he wrote for a middle school girlfriend. The other players in the room, including Simmons, Harris and Shawndarius Jennings, the younger brother of Alabama linebacker Anfernee Jennings, asked if Tagovailoa could play any songs that they knew. They settled on an early-2000s R&B song.

Tagovailoa played for about 30 minutes in all, impressing Simmons with his pipes and with his carefree spirit to turn a brief visit into a fond memory. Two and a half years later, Simmons still has the video of Tagovailoa’s impromptu performance. The day after the quarterback’s season-ending hip injury against Mississippi State on Nov. 16, 2019, he tweeted a 10-second clip of it, saying he’ll never forget it.

https://twitter.com/a_scouts_dream/status/1196212119034875904?s=20

“It stuck with me because nobody does that. Nobody does that, especially a freshman who just got to Alabama all the way from Hawaii, don’t really know nobody but his teammates,” Simmons said. “It was basically like I was a part of his family. That’s something you do with your family, just like sitting around in the living room and your whole family’s just there. That was something that really resonated with me. He really brought me in close.”

![]()

Tagovailoa’s teammates may feel like they’re part of his family, but in May 2018, two of them got to meet his biological family, spending 10 days with them on the Hawaiian island of Oahu.

Josh Casher, a former guard who graduated in 2019, had repeatedly joked with Tagovailoa during the season that he wanted to go with him the next time he went home to Hawaii. The quarterback always said the invitation was open, and Casher knew he meant it.

By the time the spring semester ended, Casher had convinced offensive tackle Alex Leatherwood to go with them, too. So Tagovailoa headed home for the first time since enrolling at Alabama and welcomed two of his teammates to the Aloha State with him.

“That could’ve easily been time that he just wanted to spend with just him and his family,” Casher said. “So for him to allow me to come and really be a part of him being back home, that let me know a lot about him right there.”

And they didn’t just go “where all the tourists go,” Casher said. They were fully immersed in the culture, including a visit to the Polynesian Cultural Center, which sits on the opposite end of the island from Tagovailoa’s high school.

They also went to Pearl Harbor and saw the USS Arizona Memorial, which commemorates the lives of more than 1,000 people who were killed aboard the ship in the 1941 bombings. That checked off a bucket list item for Casher, who had wanted to go there since he was a kid.

The Tagovailoas kept them well-fed, too. The 300-pound linemen, who ate very well at Alabama, were nearly bursting at the seams.

“I promise I’ve never eaten that much in my life,” Casher said, laughing. “I’ll tell you one thing that they’re gonna do: they’re gonna feed you whenever you go. Me and Alex, we were already offensive linemen as it is, and they told us we wasn’t eating enough.”

Leatherwood and Casher were on Alabama’s second-team offense with Tagovailoa during the 2017 season. Both were blocking for him when he threw his first career touchdown pass to Henry Ruggs III against Fresno State – Leatherwood at left tackle, Casher at right guard.

Other starters for the Crimson Tide in 2019, including Harris, right tackle Jedrick Wills Jr., wide receiver DeVonta Smith and tight end Miller Forristall, were also on the field for that play, filling out a talented group. Casher said the twos eventually got as good as the ones, but they accepted their roles and cherished whatever playing time they got.

“It wasn’t any pressure or anything like that. We just went in and we was so happy for the opportunity just to get on the field and enjoy ourselves, but we just made the most of it,” Casher said. “[Tagovailoa] was just very poised, and we knew that hey, he was a great leader. We already knew what he could do; now we just had to protect long enough for him to do it.”

Not only did they have to protect him; they wanted to. Casher said Tagovailoa’s willingness to bring him home and introduce him to his family is a perfect example of the quarterback’s selflessness and genuineness.

Flying the 4,000 miles to Oahu and experiencing the Hawaiian culture firsthand helped him see where Tagovailoa gets it from.

“How Tua presents himself – you see where it stems from with his mother and his father and his family life,” Casher said. “All of them are like that. They embrace you with love and they constantly let you know that they’re there for you. They’re just amazing people to be around.”

![]()

With four wide receivers – Smith, Ruggs, Jerry Jeudy and Tyrell Shavers – having arrived in Tuscaloosa at the same time as Tagovailoa, T.J. Simmons decided in the spring of 2017 to transfer from Alabama to West Virginia.

As his days with the Crimson Tide ticked away and he prepared to move his entire life more than 700 miles up the East Coast, the normally cheery wideout wasn’t his usual self. Tagovailoa, who had already heard the news, ran into Simmons in the hallway in Bryant Hall one day and asked how he was doing.

“He was upset that I was about to leave because we had grown together and developed a strong friendship,” Simmons said. “He was just telling me wherever I go, wherever I decide to play at, he wished me the best, and he knew that I’m a good player and I can do everything no matter where I go.

“… People are drawn to him, really. And the people that are drawn to him, he makes sure they’re good, he makes sure that their spirits are up, he’s always trying to be a good friend to everybody around him.”

![]()

Anna McCormick, in her own words, played the worst game of her life.

Two months later the sting was mostly gone, so she said she was just being dramatic. But in the moment, she took it hard.

McCormick, the strong-armed junior quarterback of Zeta Tau Alpha’s sorority flag football team, threw three interceptions in a 6-6 tie with Alpha Delta Pi on Oct. 1 – the team’s first non-win in nearly two years after an undefeated championship season in 2018.

She posted a picture of the team on her Snapchat story afterward, mentioning the tie in the caption. Tagovailoa, who had coached the team during his freshman year, messaged her to say “Good game,” but she was disappointed that her play had cost the team a win. He responded by reminding her of her nickname on the team: “QB1.”

“The way he responds to anything like that is like, ‘You can do it’ or, ‘You know that you can do it,’” McCormick said. “Like not even encouraging me from his point of view; it’s like he’s filling my mind with things that I should be saying to myself. He’s like, ‘You know what you can do. You know yourself. You got it.’”

McCormick said she appreciated that Tagovailoa didn’t scoff at how seriously she took the game or how hard she was on herself. Instead, he started offering advice over Snapchat. He asked how she was reading ADPi’s rare zone defense, told her to not be afraid to run if the play broke down and suggested that she move her feet to buy time while she looked for open receivers.

Then, noticing her guitar sitting beside her, he FaceTimed her, picked up his own guitar and spent five minutes getting her mind off of football by teaching her how to play Chris Stapleton’s “Tennessee Whiskey.”

“People respond to coaches differently, and he understood how she needed to be coached and he adapted to that,” senior and team captain Kelly Keil said.

Keil met Tagovailoa during his first few weeks on campus and invited him to a game when the 2017 flag football season started.

At first he offered only small tweaks to their game plans, but soon he was hosting practices twice a week, assigning the players positions and scribbling observations and ideas in a notebook on the sideline.

“It’s funny because it’s sorority flag football and they’re trying to use big Bama plays,” McCormick said. “They really did [work], honestly.”

Though the team did have success running the big Bama plays, Tagovailoa recognized that some things needed to be adjusted to intramural rules.

Offensive linemen must keep their hands behind their backs while blocking, so quarterbacks need to get the ball out quickly. Tagovailoa installed bootlegs and rollouts into the playbook to give McCormick more time to throw and coached her on how to read the field. He also helped the receivers learn how to catch, throwing the ball as far as he could and having them run and catch it. At practice he had them run go routes and slant routes and organized them into two lines. He threw to one line; McCormick threw to the other.

He also instructed McCormick to signal for the snap with a clap rather than by shouting “Hike!” and insisted that the players’ claps when breaking the huddle had to be in unison. If they weren’t, they had to come back and try again.

Though he hasn’t been as involved with the team as he was during his freshman year, the habit remains.

“Whether it’s a game or a practice, if we’re doing the clap and it’s off-beat, people are walking away and I’m like, ‘Get back over here!’” McCormick said, only half-joking.

His mere presence as ZTA’s coach for one year has led to the sorority’s intramural involvement rising from eight members to more than 90. It now has a JV flag football team because the demand is so high.

ZTA’s list of coaches over the last three years includes Tagovailoa, Wills, tight end Irv Smith Jr., quarterback Mac Jones, wide receivers Slade Bolden and John Metchie, former running back Damien Harris and former defensive back Tony Brown. Some of the players even recruited close friend Tre Anderson, who works for the football team, to join them on the ZTA sideline.

More so than by teaching the intricacies of football strategy or the mechanics of playing quarterback, Tagovailoa left an impression on his players simply by investing his time.

“While he’s watching you, he’s seeing one thing and then he goes immediately to his book,” said Maria Pacos, another ZTA player. “[Tagovailoa and Irv Smith] would be talking with each other and he’s like, ‘I really think this would work. Kelly should do this. Anna should do this.’ He was constantly seeing what they did good on the field and then doing it to really bring out the best of them. … He wasn’t just like, yeah, I’ll coach you, whatever. He really put in all of his efforts into helping us out.”

![]()

Simmons, who had 35 catches and four touchdowns for West Virginia this year as a redshirt junior, remains close with Tagovailoa. The two occasionally send each other encouraging words, and they texted recently about their touchdown in the 2017 spring game, which was the first collegiate touchdown for both.

It was the fifth offensive play for the Tagovailoa-led White team and his third pass; his first, a 23-yard laser to Jeudy, elicited an “Ooh!” from ESPN commentator Kirk Herbstreit. Four plays later, on third-and-7, the freshman lofted up a 15-yard pass to Simmons, who had stumbled as Tagovailoa released the ball.

“When I slipped, I put my hand down to get back up, and as soon as I got my balance the ball was already out,” Simmons said. “Tua put the ball in the air and I’m almost falling on the ground. I get up and the ball is in the perfect spot. It’s hard to even explain it. He threw the ball and he didn’t even know if I was gonna be able to finish the route. And the ball was on the money; I’ll never forget that.”

Simmons said plays like that – fitting the ball into tight windows or placing it away from defenders where only the receiver could get it – were routine for Tagovailoa during that spring. Word spread quickly about the deadly-accurate left-hander.

Inquisitive wide receivers would ask offensive coaches about how things were going in the QB room, including questions about the quarterbacks’ stats in practice.

“Tua was having a crazy completion percentage and his accuracy was like off-the-charts,” Simmons said. “I just witnessed it. He was… making throws that three-, four-year starters make and that NFL quarterbacks make.”

It was a specific NFL quarterback – a Super Bowl winner with a history of magical comebacks – whose passion, energy and leadership came to Simmons’ mind as a comparison for Tagovailoa.

“He was real Russell Wilson-ish,” Simmons said. “Say we’re in the huddle. He’ll come in and get on his knees like he’s Russell Wilson and get to telling everybody what they gotta do. It’s his presence. When he started talking, everybody gonna listen. The way he talks and the way his voice is, it lifts you up when he’s talking to you. He’ll get in the huddle like, ‘Alright boys, let’s go. We finna go out here, we finna do what we supposed to do and we finna go score a touchdown.’ When he talked, everybody just knew whatever he was saying, it was gonna go down.”

Tagovailoa so thoroughly impressed Simmons throughout the 2017 season – while Jalen Hurts was leading the Crimson Tide to a 12-1 start and a berth in the national championship – that Simmons excitedly told his new teammates at West Virginia that the unheralded quarterback sitting on Alabama’s bench was the best quarterback in the nation.

They probably didn’t believe him until Jan. 8, 2018.

Simmons had invited seven or eight of his West Virginia teammates over to his house to watch Hurts and Alabama take on Georgia in the national championship. Just after the clock struck midnight, they finally saw for themselves what Simmons had seen nearly a year earlier.

“Everybody was like, ‘You said Tua was that man. You said he was the real deal,’” Simmons said. “I was like, ‘Yeah, I told you he just needed his opportunity.’”

![]()

With one throw, everything changed. Tagovailoa was no longer considered the future. He was the present. The Heisman front-runner, the pioneer of the Crimson Tide’s new age and the face of college football – despite having never started a game.

Teammates, though, say he never changed.

Tagovailoa and Irv Smith were often stopped at ZTA date parties for photos, autographs or ukulele song requests. Not once, Smith said, did Tagovailoa turn anyone down.

“A lot of people, they’d try to ignore them or not want to have to deal with all those people, everybody harassing you, coming at you,” Smith said. “But Tua, he was always a person that would stop, look everybody in the eye, shake their hand. He listened to somebody if they wanted to talk to him.”

Immediate nationwide celebrity isn’t easy, though, nor is moving from Hawaii to Alabama and being surrounded by 35,000 fellow college students who all know who you are.

He tried to keep a low profile by wearing a hood as he walked to class, but to no avail. Still, whenever someone stopped him on campus, Tagovailoa took the time to greet them and ask how their day was going.

“We would always just joke with him, like, ‘Oh, you’re Hollywood now, you’re a superstar now,’” Smith said. “But he would just mess with us and be like, ‘No, I’m still the same guy. It’s just a little more that comes with it now.’”

Even after two years of superstardom, including supportive tweets from Wilson, whom he’s often compared to, and former NFL MVPs Patrick Mahomes and Shaun Alexander, Casher said he still sees the same humble, down-to-earth Tagovailoa as when the two were on the second team together in 2017.

“It’s never been about him,” Casher said. “He’s never thinking about Tua or stats or how his name is going to be flashed everywhere. He hasn’t changed, to me, at all, and he’s one of the biggest names in college football. He’s always remained the same.

“That’s always been my brother before he even threw his first touchdown.”

![]()

Win the team.

That’s how Alabama’s starting quarterback for 2018 would distinguish himself, in the words of coach Nick Saban. He had to win the team.

Being able to look off a safety and launch a pinpoint deep ball, as Tagovailoa did on his championship-clinching play, is one thing. Earning the respect, admiration and belief of his teammates, who had gone 26-2 under a different quarterback the prior two years, was another.

But win them he did, courtesy of the same humility and freewheeling, easygoing demeanor they had seen in him as a freshman.

“You’re willing to go out of your way for him because you know he’d do it for you,” Casher said. “When you know someone has your best interest at hand and they want to see you succeed just as much as themselves, you’re willing to go that extra mile for him.”

Alabama football practices aren’t for the faint of heart. Toughness and discipline are two of the defining values of Saban’s philosophy, and the coaches ingrain them by continuously pushing their players’ limits and testing their breaking points.

Tagovailoa, though, took a different approach to his newfound leadership role as a true sophomore.

“If we weren’t necessarily having a great practice [in 2018], he was good about lifting guys up. Not by yelling or screaming; that wasn’t his leadership style,” said Layne Hatcher, Alabama’s fourth-string quarterback at the time. “His leadership style was to go put his arm around a guy and maybe make a joke and get stuff going right.”

As a fellow quarterback, Hatcher was in position meetings with Tagovailoa daily. While the left-hander showed that he knew the playbook and could answer quarterbacks coach Dan Enos’ questions, his greatest assets were his speedy processing and his ability to anticipate when a receiver was about to get open.

Hatcher had, of course, seen and heard plenty about Tagovailoa before enrolling, but he didn’t get the full experience until he watched him in person during summer 7-on-7s.

“I just saw some very unique arm talent,” Hatcher said. “Not necessarily arm strength, just the ability to kinda make the ball dance in the air is how I always said it.”

Dance?

“He can get it over a linebacker and under a safety, in a tight window with a guy on the back of the receiver and hit them in stride. … If you can get it up and down or just put it in those tight windows, I think that’s something pretty special.”

Hatcher said the best throw he saw Tagovailoa make was the first of his 43 touchdown passes during his sophomore season.

On Tagovailoa’s first drive of his first game as the starter, an unblocked Louisville defender charged at him, forcing him to spin around into the path of another rusher. He spied a corner chasing Jeudy along the goal line and, seeing that the corner’s back was to him, he lofted up a risky pass as he fell backward and landed hard on the ground.

If the corner had turned around, it could just as easily have been intercepted. But he didn’t, and it wasn’t.

7-0, Alabama.

The Tagovailoa era was underway.

“There were some times in practice when we’re doing two-minute drills or something,” Hatcher said. “You hear the coaches kinda yelling, ‘No, no, no, no, no!’ and then, ‘Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes!’ because he’s doing something crazy. … He makes some crazy throw that we haven’t really talked about reading it this way, and everybody just kinda laughs.”

![]()

A few days after the 51-14 win over Louisville, Casher was chatting with Tagovailoa when the quarterback told him that he often prayed on Friday nights about the following day’s game.

The following Friday, the night before Alabama played Arkansas State in its home opener, a tradition was born. For the rest of the season Casher and Tagovailoa joined outside linebacker Anfernee Jennings and safety Deionte Thompson for prayer and a weekly devotion the night before every game.

When their evening football meetings ended, they re-convened at Tagovailoa’s room, either at his apartment in Tuscaloosa or in a hotel when on the road. Tagovailoa often led the devotions, but no topics were off-limits during their discussions, which sometimes lasted more than an hour.

“It wasn’t all about football, but we would just talk, just about how we were doing personally, how we were doing spiritually and really that was our time to just connect as brothers,” Casher said. “… It was like we had a little family meeting. It was just an amazing time where we were able to grow together and basically just ask God to go before us. Before we went into war, we asked him to go before us and for him to go into the battlefield before we did.”

The Crimson Tide won its next 13 battles en route to a spot in the national championship game against Clemson. As they had all season, Tagovailoa and Casher, both members of Alabama’s spiritual leadership team, met up in Tagovailoa’s hotel room in Santa Clara, California, to pray and study the Bible.

They were joined by team chaplain Jeremiah Castille, who holds an optional chapel for players four and a half hours before every game. He taught about the word “amen” the day of the national championship, but he gave Tagovailoa and Casher a sneak preview the night before.

He explained that though the originally Hebrew word is usually thought of only as an ending to a prayer, it is almost universally understood to mean “this is true.” Used before a section of text, it assures the reader that what follows is truth. Used after, it seals and confirms the message.

“You would’ve had to have seen [Tagovailoa’s] eyes – the enthusiasm of receiving something new,” Castille said. “And I think that’s what makes Tua a great athlete: He’s always hungry for, ‘How can I get better?’”

Casher said that night is his favorite memory with Tagovailoa because those kinds of moments transcend football. Castille said they “bring hearts and minds together” and give the team the synergy it needs, with players striving to help each other play at their highest level.

During Castille’s days playing at Alabama under Paul “Bear” Bryant, the legendary coach wouldn’t let players leave practice until they impacted the practice in some way. Even in Tuscaloosa’s oppressive late-summer heat, a player couldn’t be done for the day until he made a play.

“That’s what Tua does when he’s in the game. He’s like, ‘Hey man, I’m gonna impact this game,’” Castille said. “He takes that to life [and says,] ‘Hey, I’m gonna have an impact on life. On whoever God brings my way, I’m gonna have an impact.’

“… It’s one thing to have a football legacy. You can have a football legacy without a spiritual legacy. He has both. And to me, that’s what makes him unique and special.”

Amen.