Campus monuments, memorials tell a one-sided story

December 5, 2019

The University of Alabama landscape is dotted with monuments to the Confederacy and important sites of the civil rights movement. These are rarely discussed on campus tours or at other events. Some faculty and students believe that the University should be more open and honest in telling its own history.

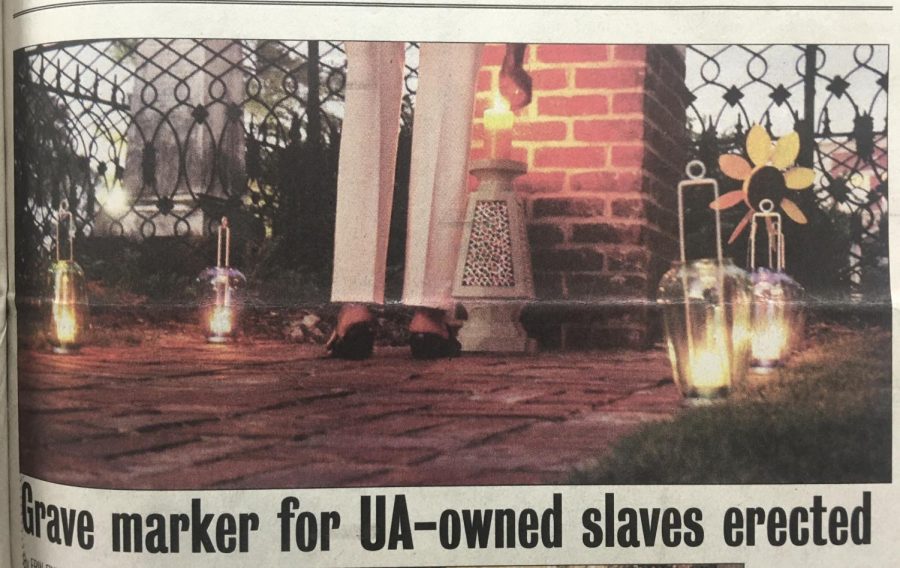

Set on a squat brick path, a short branch off the sidewalk to the Bus Hub, four grave markers sit nestled against the back of the Biology Building. In front of the fenced-off markers, a plaque with only seven sentences is on display.

But few students ever see the words on it, primarily due to its location.

It is the University of Alabama Faculty Senate’s apology for slavery, honoring those “whose labor and legacy of perseverance helped to build the University of Alabama community since its founding.”

The plaque is the only such marker on campus.

“You have to go find the ways the University has tried to physically reconcile with race,” said Cierra Roberson, a graduate student in gender and race studies. “But you blatantly see Confederate monuments like the boulder in front of Gorgas … It informs how I think the University administration feels about my being a black woman on campus.”

There are 15 plaques on campus that catalog events from the Civil War and prior. Two mention slaves or enslaved labor, and one of those two is the slavery apology marker, erected in 2004.

Hilary Green, associate professor of history, said the University has a larger story it is not telling.

“The justification of a pro-slavery stance was in [the University’s] DNA, and it became geared toward defending white supremacy and Jim Crow when slavery was over,” Green said. “[The slavery apology] marker, without context, is insufficient. Unless future generations just stumble across it, they will not notice history.”

The University of Alabama was ahead of many southern colleges when it approved the apology marker in 2004, Green said. The University of Virginia, hailed as a model of institutional racial reconciliation in recent years, installed a similar marker in 2007.

“We have these bold attempts, but the efforts haven’t been sustained,” Green said. “The University’s problem with reconciliation is that it is seen as a one-time event rather than a sustained effort.”

Green alleges that the University administration claims the public relations benefit of the independent projects of professors rather than direct money to official racial reconciliation projects.

Christine Taylor, UA vice president and associate provost of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, primarily referred to the extracurricular scholarship of Green and John Giggie when asked for a comment on this article.

Giggie is the director of the Summersell Center for the Study of the South at The University of Alabama, as well as the editor of the Tuscaloosa Civil Rights Trail pamphlet.

The Tuscaloosa Civil Rights Task Force, the organization responsible for that project, is separate from the University. It was created by commission of Mayor Walt Maddox and the Tuscaloosa City Council in 2016.

Green’s scholarship, which draws on University archives, resulted in her creating a walking tour of campus known as “Hallowed Grounds,” which details the history of slavery on campus.

Meredith Bagley, associate professor of communications studies, also sponsors an unofficial tour of important civil rights-era sites at the University.

Roberson took an official campus tour as part of a class last fall. She did not believe it reflected the experience of black students at the University.

“The campus tour [given by the Capstone Men and Women] is ahistorical,” Roberson said. “There are so many opportunities, not to just bash the University, but to state the facts and tell people what happened here … The tour erases black life, black trauma and black memory on this campus.”

Billy Field, an instructor in the Honors College, wants the official campus tour to include more sites related to the desegregation movement on campus.

“I think that potential students on campus tours should be taken to the site of the Stand in the Schoolhouse Door and told the story,” Field said. “They should be told about its importance in the history of the whole country.”

While the plaque at Foster Auditorium is comprehensive in describing the event as the primary catalyst for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Field believes it should be a focus of official campus tours.

Field teaches an Honors College filmmaking class that requires students to produce documentaries on Alabama history. Many projects feature civil rights history, and Fields is often surprised by how little students know before they begin.

“A lot of my students come here thinking all the racial problems in America were solved after the civil rights movement,” Field said. “And that’s just not true … I think there should be a strong program focused on racial reconciliation at the University, where there’s every kind of opportunity for students to come together.”

Green said that she often hears students voicing their frustration with the current state of the official campus tour.

“The tour, unfortunately, contributes to our students feeling like they’re being lied to from the beginning,” Green said. “I hear this constantly from white students, black students, international students when they finally learn the history of slavery at the University.”

The Capstone Men and Women do not have a specific policy on addressing historical matters of race on campus tours, advisor Lucy Arnold Sikes said.

“Our tours are designed to showcase the campus to prospective students,’ Sikes said. “This includes campus grounds and facilities they will frequent once they enroll at UA. The tour route includes Malone-Hood Plaza and the Autherine Lucy Clock Tower. Tour guides can answer any questions that come up, including those that involve the University’s history.”

The University of Virginia is often seen as a leader in racial reconciliation among colleges in the United States. UVA’s president is on the leading edge of historical research and racial activism, publishing a Commission on Slavery in 2018.

Kirt von Daacke, assistant dean of arts and sciences at UVA and co-chair of that commission, said that the most difficult thing for a university’s administration is taking the first step toward reconciliation.

“Universities may fear that the history will be bad for the brand, bring bad press or cause protests,” von Daacke said. “But when you begin truth-telling, you find you invite more people in, and everyone learns and benefits from it.”

The UVA Commission on Slavery and the University were only created after several years of student activism. Students’ efforts were sparked by inadequate attempts at apologies and racial reconciliation, von Daacke said.

As with the protests after Riley’s resignation, campus-wide UA student mobilization on this issue has been episodic.

Von Daacke said that a university’s administration will likely only respond to a respectful, comprehensive student movement. He emphasized the effectiveness of letter-writing campaigns, non-destructive publicity stunts and peaceful protests.

“Our students went out and tackled these issues in ways that were additive and inclusive,” von Daacke said. “There’s a student group focused on reviewing monuments at the university, discussing what needs to be rewritten, recontextualized or removed … Some covered a statue of Thomas Jefferson in Post-it notes to get their point across.”

The Memorial to Enslaved Laborers organization was one of the earliest student groups to mobilize at UVA following the installing of their apology marker in 2007.

While they did not have the authority to build a memorial, the group held design competitions and sparked a larger campus dialogue on the issue of racial reconciliation.

As a result of the group’s actions and their own findings, the UVA commission, along with their board of visitors, has resolved to build such a monument on campus.

The memorial will be placed prominently near the university’s Rotunda. A dedication ceremony is planned for April 11, 2020.

UVA has also founded the Universities Studying Slavery coalition, a group of collegiate institutions dedicated to “dealing with race and inequality in higher education and in university communities as well as the complicated legacies of slavery in modern American society,” according to their website.

The University of Alabama has been in talks to join this coalition since November of last year after a resolution from the UA Faculty Senate. Taylor said the University will “move forward” to become a part of the group, but no official announcement has been made so far.

The UA Faculty Senate also resolved to create its own commission to study slavery and the University last November. It has yet to officially form.

Green, a member of that commission, said members have only met for preliminary discussions twice in that time. However, she remains “cautiously optimistic” about the commission’s potential.

Confederate monuments at The University of Alabama are protected under the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act, which prevents the removal of monuments and renaming of buildings over 40 years old, according to UA Faculty Senate President Rona Donahoe.

President Stuart Bell said that the University has been working on addressing its history over the last several years in particular.

“Much work has occurred, and more is ongoing on our campus,” Bell said. “Many of the historic markers on our campus honor those who have more recently made significant and lasting contributions to moving our campus forward while championing equality, including the establishment of plaques and a clock tower dedicated to Autherine Lucy Foster, Malone-Hood Plaza, Judge John England, Jr. Hall and others.”

Provost Kevin Whitaker highlighted the University’s establishing of the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, as well as Taylor’s work toward reconciliation initiatives. Whitaker said that “understanding our past is an important priority.”

Roberson believes the University is attempting to move forward without addressing events before the civil rights movement. She said that their presentation of UA history is selective at best.

“History is cyclical if we don’t talk about the past,” Roberson said. “[The administration] can never create a better environment for the students if they don’t acknowledge what the University has done and what black students have gone through.”

Reading Between the Headlines

October 1969: Are Blacks At UA Still Slaves?

“Any reader who cannot readily draw a parallel between the working conditions of Associated Cleaners’ maids and janitors, Slater’s employees and the slaves of ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ will find this article difficult to understand,” CW columnist R. Edward Brown wrote.

August 1988: UA holds race relations conference

“I am less than optimistic about the future,” speaker Leon Litwick said. “Racism remains and is expressed more suddenly in our society. The victims of that racism continue to grow and the consequences continue to affect every aspect of American lives.”

September 2004: Grave marker for UA-owned slaves erected

“Wearing a sticker that says, ‘Hate is not a UA value,’ is a sugar-coated solution to the problem,” student Stephens Williams said.

November 2018: Slavery Commission to study historical racism

“When new prospective students are brought to campus and are given the tour of campus, they show you the President’s Mansion, and what they don’t tell you is that what is typically described if anyone asks as the ‘gardeners’ homes that are behind the president’s mansion,’ they’re actually slave quarters,” Rona Donahoe, UA Faculty Senate president, said.