Students speak out on social media sex trafficking

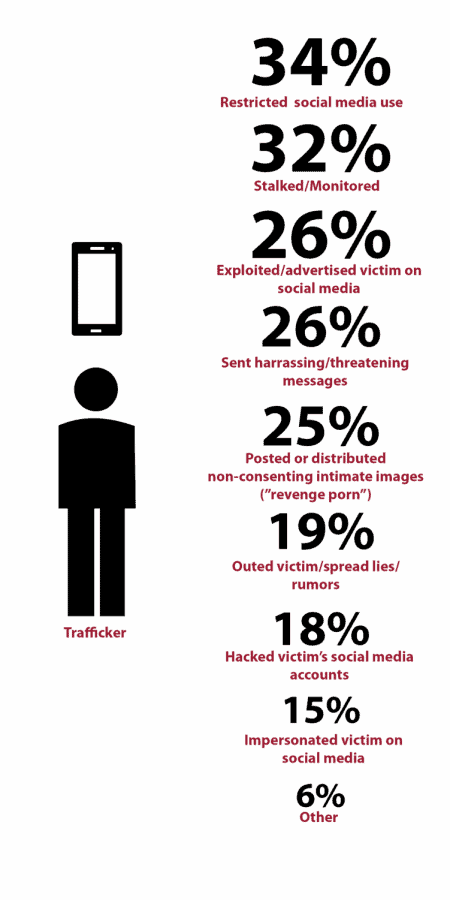

Polaris, a non-profit combating human trafficking, conducted a survey of 73 survivors. Of those survivors, these figures show how many were targeted on social media as a form of control. CW / Rebecca Griesbach

November 21, 2019

In an age of snaps and swipes, safety is an increasing concern for social media users, especially those who are college-aged. In the cyber world, unwanted advances, and even trafficking, have taken on a form that is often normalized or difficult to detect.

For students, the rising cost of college can seem like an inescapable burden. While many take on odd jobs or work in the public sphere, however, some look to the fast cash sex work can bring. Sex work, as opposed to sex trafficking, is consensual, meaning the person willingly takes part in the sale of sex – and it is becoming an increasingly online venture.

[READ MORE: College-age “sugar babies” make cash, gifts for companionship]

But, for every student who chooses to take advantage of online sex work, made available through premium Snapchats or sugar baby sites, there are several social media users who are faced with flurries of unwanted requests.

Kiera Phillips, a senior majoring in computer science, has encountered traffickers through Snapchat. She didn’t know these men, who added her out of the blue, but they were willing to pay her big bucks ($3,200, one told her) for suggestive photos. Each time she refused, they’d raise the price.

“It was weird,” she said. “It was just some random guy, and he tried to send proof that he would send me money. I didn’t trust it.”

Three days later, Phillips said her friend received the same offer. That’s when she realized the limits of privacy on social media and how widespread these unsolicited messages were – so much that it had become a seemingly normal occurrence for her.

“At the end of the day, you can’t really stop people from being people,” Phillips said. “I’m pretty sure guys do it all the time to get money and pictures out of [users].”

College-aged women are disproportionately affected by sex traffickers online. Women represent 71% of sex trafficking victims according to the Global Data Hub on Human Trafficking, with the most common ages being 18-20 years old.

Through trafficking has occurred on the internet since its advent, a 2018 Polaris study found that more social media platforms allow for an increase in online crimes. Case data from January 2015 through December 2017 recorded 845 potential victims recruited on internet platforms.

In Alabama, it is illegal to “solicit, compel, or coerce any person to have sexual intercourse or participate in any natural or unnatural sexual act, deviate sexual intercourse, or sexual contact for monetary consideration or other thing of marketable value.” Categorizing the crime as “prostitution,” the state law penalizes all parties involved.

Usually, the people sending these messages are complete outliers in user’s lives – most of the time, older men whom the users have never spoken to before. That was the case for Mackenzie Dietz, a junior majoring in global science and philosophy, who has received lewd messages mostly through Instagram and Snapchat.

“I felt irritated,” Dietz said. “That would be the best word to describe it, that somebody would have the audacity to just say, ‘Let me see naked pictures, and I’ll give you some money for it.’”

That reality led Kayla Whitner, a senior majoring in creative media, to delete Snapchat and other platforms. Its format, she reasoned, allowed for this type of behavior – for the “super weird” messages she had received time and time again. She only uses Instagram now, but every now and then, she faces the same problem. For Instagram users, Whitner explained, these types of messages are usually sent and filtered into the message requests folder, which is kind of like a spam folder.

“Random people get really bold, whether it be older, sugar daddy-ish men who say, ‘Hey beautiful, you wanna fly here or there?’” she said. “It’s never really explicitly sexual. I mean, sometimes.”

CRACKING DOWN?

David Imuetinyan, a first-year grad student studying mechanical engineering, suggested that one possible way of combating the issue is to start with social media platforms themselves, such as Facebook.

“If [Facebook] can really monitor our messages, and I know its prying into our privacy, they can be able to track down sex traffickers,” Imuetinyan said.

According to Facebook’s community standards, the site’s policies on nude photos are nuanced, allowing for content intended as a “form of protest, to raise awareness about a cause or for educational or medical reasons.” The standards also prohibit users from coordinating any activity that is intended to or is “likely to cause harm to people, businesses, or animals.” Listings, in addition, “may not promote the buying, selling or use of adult products or services.”

A common assumption is that these standards only apply to posts. According to a 2018 Bloomberg report, however, a Facebook official confirmed that messages are also scanned for violations. But, here’s the catch: The app’s automated systems mainly scan for “known images” or links associated with criminal activity, rather than the conversations that precede them.

While some argue that it is up to owners of platforms to control content, others suggested that the University and the city should have a larger role in combating unsolicited sexual messages on social media.

“Any report filed related to social media sex trafficking is forwarded and investigated by the Human Trafficking Task Force to which UAPD has several officers assigned,” said Deidre Stalnake, Director of Strategic Communications. “These officers work in conjunction with officers from the other local agencies to investigate and arrest the individuals responsible. UAPD also places information on our website (police.ua.edu) and in the Safer Living Guides to help inform our community how to stay safe while on social media platforms.”

But, the Human Trafficking Task Force, which was created in 2018, is not a full-time unit.

The lack of a full-time unit can create a barrier to understanding the complicated webbing of social media sex trafficking.

Lieutenant Teena Richardson noted that the crime looks different now, as sites like Backpage and magazines that advertise sex for sale are obsolete. In order to address sex trafficking advertisements, officers would have to spend time studying them and their varied forms. Instead, Richardson said, issues are investigated on an individual basis and must be brought to Tuscaloosa Police Department’s attention by the victim.

While many perpetrators are older, Imuetinyan said the school has a responsibility to address student offenders. For Whitner, the campus environment must also change.

“Creating a cleaner, more productive social scene may lead to better social interactions, yet it may not be possible since when students get out of class, they want to do their own things,” Whitner said. “There are some things that are going to keep on getting crazier and out of hand.”

To get help, report a tip about a potential case of human trafficking, find service referrals for victims of trafficking, or request training or technical assistance, contact the National Human Trafficking Hotline by calling 1-888-373-788 or by texting “BeFree” (233733), via live chat or email. Services are available toll-free 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.