‘Are Alabamians worth any less?’ Citizens express concerns at ADEM permit hearing

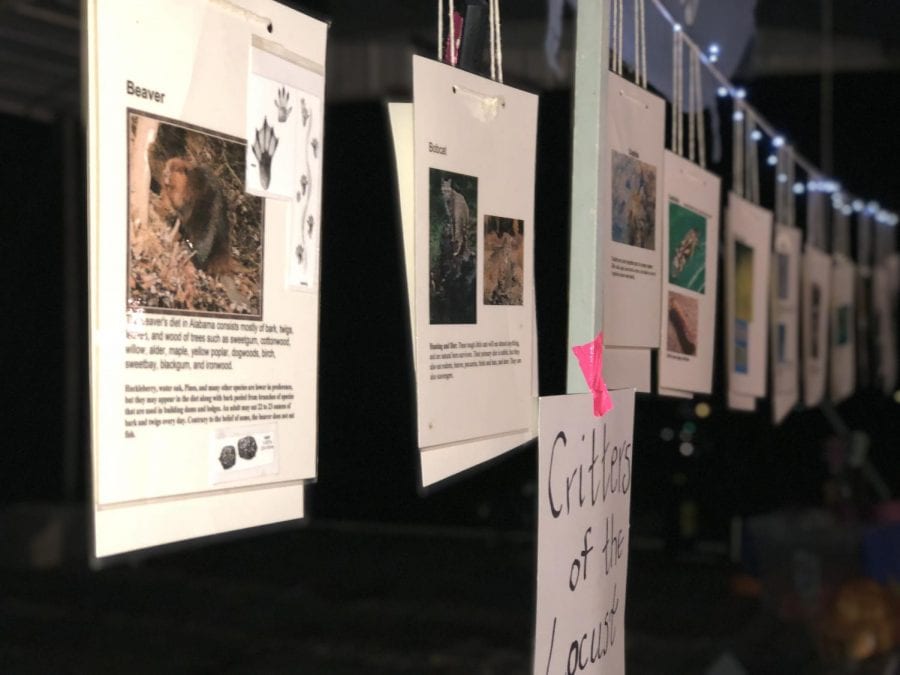

Citizens posted photos of endangered Locust Fork animals at an ADEM hearing at the Blountsville American Legion. CW / Alex Jones

November 21, 2019

In a public hearing held months after a massive E.coli spill killed about 175,000 fish in the Black Warrior River, several citizens reached a grim conclusion: Alabama holds Tyson Foods to lower environmental standards than any other state.

The Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM) held a public hearing in Blountsville on Tuesday night to hear public opinions on the renewal of Tyson Foods’ Blount County chicken processing plant’s wastewater disposal permit.

At this hearing, citizens expressed outrage at the leniency of ADEM’s regulations of Tyson, regulations which are far more stringent in other states. No one from ADEM spoke during this event except to explain the hearing and to introduce the citizens speaking. The hearing was solely to hear people’s complaints and opinions.

These hearings must be held every five years and are generally routine occurrences. After Tyson’s E.coli spill, however, this year’s hearing was much livelier, with approximately 200 people in attendance.

[READ MORE: Months after a spill contaminated the Black Warrior River, ADEM is still silent]

Rod Hance, the environmental manager of Tyson’s North Alabama complex, spoke first, emphasizing that the hearing was nothing more than “a routine renewal of [Tyson’s] permit.”

“There is no direct discharge to the Locust Fork, and there is no planned expansion to the Blountsville plant,” Hance said. “Tyson is committed to being a good corporate citizen in Blountsville and anywhere we have a facility. Our team members come to work every day and diligently work to make sure we are protecting the environment, meeting the requirements of our permit and meeting the requirements of state and federal regulations.”

For the next two hours, dozens of citizens voiced their concerns. While many were unhappy with Tyson, the majority of the blame fell onto ADEM for being too lenient in their regulations of Tyson’s Blount County plant.

Much of the citizens’ anger stemmed from the knowledge that Tyson could do better if it was required to.

Debra Gordon-Helman, a member of Friends of the Locust Fork River, a group formed in 1991 with the goal of protecting the natural health of the Locust Fork, said that “environmental agencies similar to ADEM in other states hold Tyson to higher discharge regulations, with which they comply.”

“The responsibility for Tyson not using state-of-the-art technology, technology which it uses in other states, rests solely on you, ADEM, for not imposing more stringent regulations,” Gordon-Helman said. “I find it unacceptable and unconscionable that the people of this county and of this state are not treated to the same protections as these other states. It makes me angry. Are Alabamians worth any less? I know you can do better, I want you to do better and subsequently, Tyson will do better. ADEM, you hold the wellbeing of my county in your hands.”

Nelson Brooke, who serves as Riverkeeper and Executive Director of Black Warrior Riverkeeper, spoke at the hearing, echoing a need for more stringent regulation.

“Tyson can accomplish better water treatment, but they’re not going to step up that plate if you (ADEM) don’t set it for them, and that’s what we are asking from ADEM: to be more proactive and protective of this incredibly important area, its community and its local water resources which are the lifeblood of this county,” Brooke said. “This is a true gem.”

Brooke also brought attention to the fact that the plant’s wastewater discharge point is near a “very popular public access point” to Graves Creek, which flows into Locust Fork, a Black Warrior tributary. It’s a place, Brooke said, where “families have, for generations, swam, fished, played, picnicked and just enjoyed being by the water.”

The bacteria levels coming out of the storm water discharges of that facility are a “threat to public health,” Brooke said.

“They are not controlled by this permit, and they need to be,” Brooke said. “A lot of people who are being exposed are not aware of their exposure because of a lack of signage and public notification. This company has been allowed to discharge too much of too many different pollutants into Graves Creek and Locust Fork for too long.”

Sam Howell, another member of the Friends of the Locust Fork River, said that “ADEM needs to be more proactive in forcing federal and state regulations, rather than just reactive when receiving complaints.”

Howell did cut ADEM some slack, however, for “being one of the least funded, if not the least funded, environmental management agencies in the country.” According to a 2017 AL.com article, ADEM would have had to “raise its total funding by $7.9 million just to climb out of last place nationally for environmental funding.”

Howell called the figure “embarrassing.”

“Please be the best you can be,” Howell told ADEM representatives, holding back tears. “The people and the critters of the Locust Fork Watershed deserve it.”

Others were more assertive in their displeasure with ADEM’s lenient policies regarding Tyson’s wastewater treatment and disposal.

“Blount County needs Tyson Foods, and discharging wastewater is a necessary evil, but it is very difficult to think of this beloved river being used, frankly, like a toilet,” Gordon-Helman said.

What Gordon-Helman wants “is for ADEM to require the very best practices possible and the cleanest discharges possible, which is not now the case.”

“Learning that 1.2 million gallons of perfectly clean water is taken from the aquifer, contaminated with chicken waste, bacteria, nutrients and toxins, treated ineffectively and then discharged into Graves Creek, which then flows into the Locust Fork, is truly unimaginable, and yet it is true,” Gordon-Helman said. “The fact that it has been cited at least 16 times in the last year and a half for toxins is proof of that.”

All this wastewater causes Graves Creek to stink, but it is not only disgusting to citizens. Tyson’s wastewater is also bad for the environment, according to Betsy Dobbins, a Samford University biology professor.

“There is evidence of statistically significant impact from the facility on Graves Creek, and of Graves Creek on the Locust Fork,” with respect to nitrogen levels in the water, Dobbins said. This is detrimental to the animals of Graves Creek and Locust Fork. Upon hearing this information, people in the crowd began chanting “save our river” and waving printed out images of native wildlife to Locust Fork.

“Your mission,” said Gordon-Helman, quoting ADEM’s mission statement, “is to ‘assure for all citizens of the state a safe, healthy and productive environment.’ Can you say in good conscience that you steward our river and others in Alabama in accordance with your mission?”

That was the overarching question of the night. Do ADEM’s policies, with respect to Tyson Foods, have Alabamians’ best interests in mind, or do they compromise health for the sake of large corporations? Overwhelmingly, the citizens present declared that ADEM cared more for the latter.