If you have chalk, five minutes and the inclination, you can create a message that will be seen by literally thousands of people on campus. And if you walk past the Quad or the Crimson Promenade on your way to class, you have firsthand experience evincing this.

You’re also probably starting to feel a little annoyed with both sides of the abortion issue.

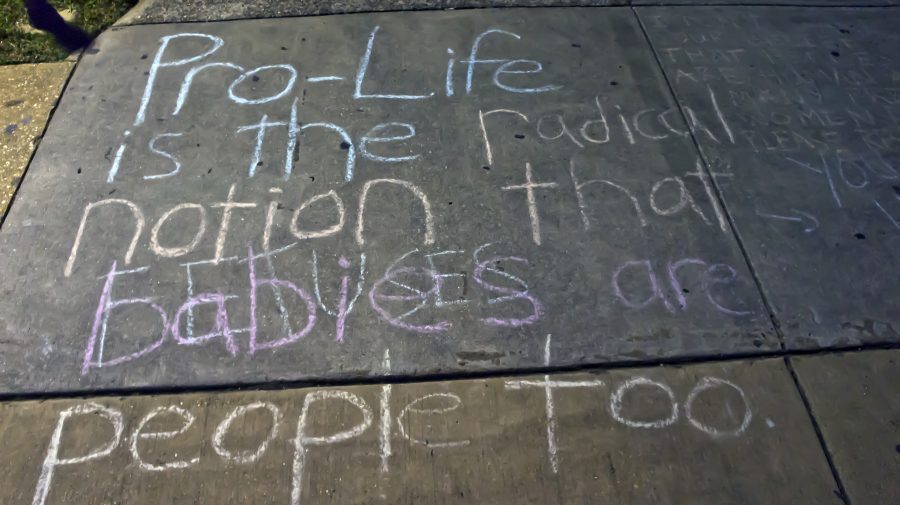

Last week, the following words appeared in colorful block letters on the Crimson Promenade; “Hey, I just met you/ and this is crazy/ but don’t abort me/ cause I’m your baby.” This is just one of many similar messages, others of which read “Life is beautiful,” and “We believe in women’s rights to be born.”

A few days later, responses started to crop up. One, etched alongside the “Call Me Maybe” shout-out, reads, “…Please attempt to be less tasteless.” Another, more to the point, says, “You don’t know a damn thing about us. NEVER assume you are the moral superior because of your scruples.” Others hash out common pro-choice arguments, and many responses attack the original pro-life messages and their authors.

There’s one thing that is certain about these messages; no one has revised their own views on abortion because of them.

Political discourse and activism are valuable aspects of academia, and they are spurred on by the spirit of intellectualism that a collegiate environment creates. But it’s very easy for impassioned students to cross the line between meaningful dialogue and rhetoric.

Last year, students gathered for the Not Isolated March to fight social inequality at the University. Others would gather at the Crimson Promenade to hold demonstrations opposing House Bill 56, a proposed immigration law that was decried by many as intrusive and racist. Later that same year, a protest was held at the same location to protest Senate Bill 5, a controversial “personhood bill” that would have radically altered the law surrounding abortion, birth control and the responsibilities of obstetricians.

These are all examples of constructive political action. In each case, students raised awareness of a particular issue, and interested passersby were directed to more specific, persuasive sources of information.

By contrast, all the chalk messages did was make people angry.

We’re all surrounded by political sentiment, and there’s a right and a wrong way to handle it. Insults, mantras, fear mongering and hatred are all too common on campus. They can be found everywhere from casual conversations to political cartoons and bumper stickers, and they add nothing to Bama’s political culture.

So don’t waste your chalk.

Nathan James is a sophomore majoring in public relations. His column runs on Thursday.