Since the early 1900s, the Alabama Legislature has been inching toward legalizing gambling statewide. It started small, with wagering on dog and horse races in 1902, and then passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988, permitting casinos run by Native American tribes on tribal-owned land.

Earlier this year, legislators geared up for their nearly annual attempt to pass a bill that would open the floodgates to gambling in Alabama, giving its residents access to a lottery and sports gambling, and allowing casinos in certain counties after a bidding process. In February, for the first time in the state’s history, a two-bill gambling package passed the Alabama House and was sent to the Senate.

House bills 151 and 152 would establish an Alabama Gaming Commission and crack down on illegal gambling by increasing penalties for this crime in the state. With little pushback from lawmakers and either side of the party line, this was the only piece of gambling legislation to receive public support from the governor, House speaker and Senate president.

Tax revenue from this gaming plan was initially projected to exceed $1 billion annually, which would be put toward a few of Alabama’s high-priority issues, per an amendment added by the Senate.

For the first three years, the funds would go toward “ongoing capital improvements and infrastructure projects,” and in March 2029, the revenues would be split three ways between the general fund, education, and roads and bridges.

The Senate will be sending a very different package of bills back to the House, gutting the kinds of gambling allowed down to a lottery and a compact between the Poarch Band of Creek Indians. And now, there’s a dark horse in the running for who would take most of the revenue.

Some senators believe that the tax revenue from gambling is the only way to complete the 4,000-bed mega-prison proposed back in 2021 for Elmore County and begin construction on a second mega-prison in Escambia County.

Gov. Kay Ivey and lawmakers initially set aside $1.2 billion for the construction of the two prisons. The cost of the Elmore County facility, originally gauged at less than $700 million, has now risen to $1 billion due to changes in design and inflation. An updated cost estimate for the Escambia County facility is not yet available but is expected to be somewhat smaller.

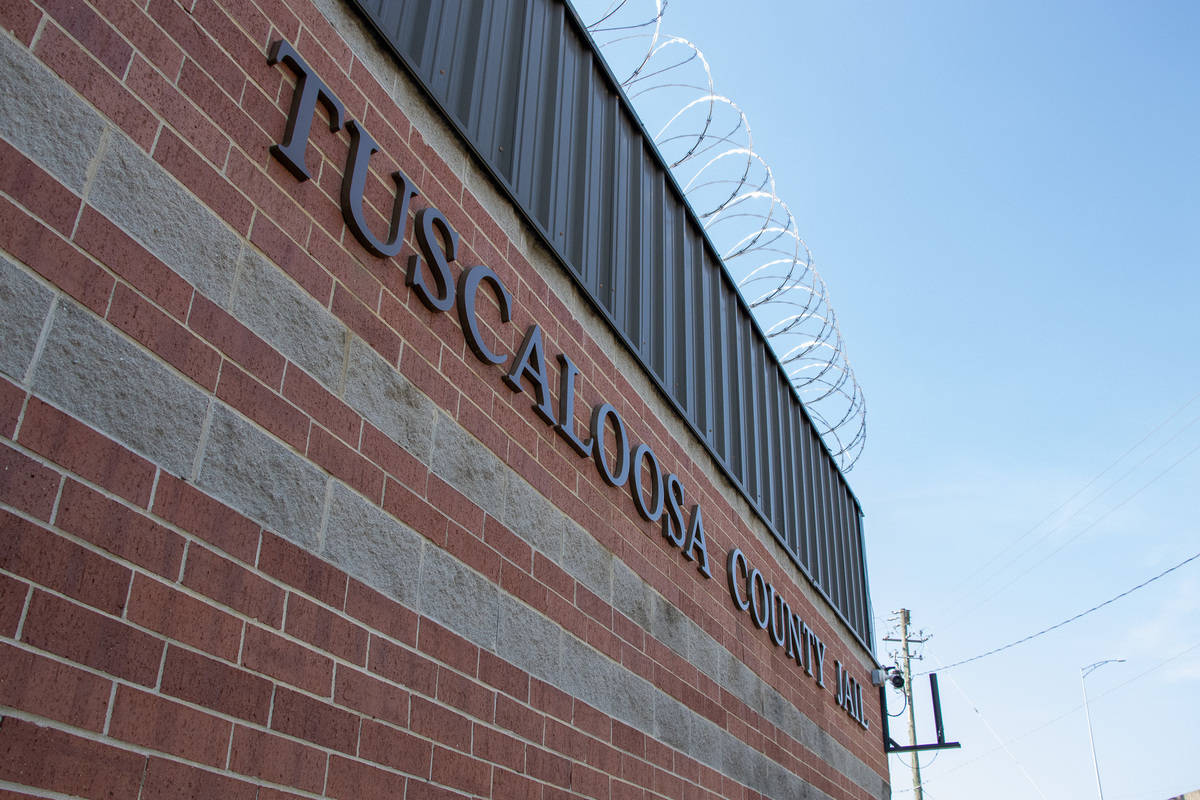

The Department of Justice is breathing down Alabama’s neck given the state of its overcrowded and underfunded prisons, which are facing a lawsuit, and tax revenue from a gaming bill is quick cash.

The Legislature wants prisoners out of these unsafe and outdated prisons without doing anything about the predatorial administration and the parole laws that the administration doesn’t adhere to anyway. So what are a couple more mega-prisons in Alabama, one of the deadliest states to be a prisoner in? And where’s this money going to come from?

The state lottery, said Sen. Greg Albritton, the man with a terrible plan. He proposed that Alabamians participating in the lottery shouldn’t see the benefits of the public revenue from the lottery and casinos, unless they find themselves within a mega-prison in Escambia County, the county Albritton represents. He sees the new revenue as a way for him to bring glory to himself back home and doesn’t care whether the funds go toward the things Alabamians actually want to see improved.

The only acceptable way to use revenue from gambling in Alabama is to return it to the communities by improving roadways and education, as initially intended. The Legislature made its bed when it let Alabama prisons get to such a dismal state that federal investigators had to step in, and it shouldn’t expect residents of the state to bail it out if it doesn’t first rebuild and improve our communities.