Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., was indicted Sept. 22 for allegedly pocketing hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes, including literal bars of gold. However, those who pay attention to Alabama politics may have some trouble figuring out what exactly Menendez did wrong.

In Alabama, ever since Gov. Robert Bentley signed Senate Bill 445 into law in 2013, corporations are free to donate as much money as they want to political candidates.

Thanks to SB 445, Gov. Kay Ivey’s reelection campaign received an eye-popping $235,000 in donations from Alabama Power. That’s almost a quarter of a million dollars from the same Alabama Power that, according to the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, is in contention for the least efficient utility company in the country.

In 2018, Alabama Power was fined $1.25 million for polluting groundwater. Five years later, in 2023, the Alabama state government is still trying to give Alabama Power a sweetheart deal so the company doesn’t have to properly and safely dispose of their coal ash.

Bentley allowing corporations to flood elections with cash has supercharged this seemingly quid pro quo approach to policy making.

Of course, political campaigns need to raise money somehow: to pay for ads, to hire campaign staff and to host rallies. I’ve personally donated to more than a couple candidates for public office in my home state of Virginia.

But a system where corporations, PACs and the super rich handpick which candidates have a fighting chance is both unjust and undemocratic. When companies getting lucrative public contracts donate thousands upon thousands of dollars to the campaigns of the people who approve those contracts, we need to be asking some hard questions.

Here in Tuscaloosa, every single sitting city councilor accepts donations from companies that do business in Tuscaloosa, including businesses that bid for public contracts. For example, J.T. Harrison Construction Company was recently awarded a $7.3 million contract to build a new YMCA. J.T. Harrison Construction and its founder and president, Tim Harrison, donated to the campaigns of City Councilors Cassius Lanier, Norman Crow and Raevan Howard in 2021, as well as Mayor Walt Maddox.

They might not have received bars of gold, but I would sure feel awfully grateful to anyone who gave me $500 or $1,000. Councilor Lanier was absent from the Sept. 12 City Council meeting, but neither Crow nor Howard recused themselves from the vote to tentatively award the YMCA construction contract.

Both voted to give $7.3 million to J.T. Harrison Construction Company.

Am I saying the Tuscaloosa City Council isn’t following Alabama’s competitive bid law to the letter? No, I’m not. J.T. Harrison Construction was the lowest of five bidders for the YMCA contract. But federal government contractors are expressly barred from making any political contributions for good reason.

Democratic politics don’t just require the absence of impropriety. They require the absence of the appearance of impropriety.

When Tuscaloosa residents know real estate companies donate tens of thousands of dollars to the mayor and to City Council members, they may start doubting whether the city government has purely selfless reasons for its horrifying inaction on Tuscaloosa’s housing crisis. Worst of all, some members of Tuscaloosa’s current city council haven’t even tried to avoid the appearance of impropriety.

Going into the last week of May 2021, more than a month after the runoff elections, City Councilor Matthew Wilson’s campaign had a balance of $0.65. That week, he received two donations of $1,250, one from Pride PAC II and one from T-Town PAC II. On May 28, Wilson repaid $2,500 in loans he had made to his own campaign, leaving the campaign once again with a balance of $0.65.

Did anything illegal happen? No, of course not. PACs are meant to give money to campaigns, Wilson had loaned a lot of money to his own campaign, and paying off debt is a valid campaign expenditure.

It is also completely accurate to say that a month after Wilson was elected, thousands of dollars from two PACs run by Michael Echols ended up in Wilson’s pockets. Before the election, Echols’ PACs had exclusively been giving money to one of Wilson’s opponents, Katherine Waldon, and not to Wilson.

Free from impropriety? I believe so. Free from the appearance of impropriety? Of course not. After all, donating to a campaign a month after an election won’t change which candidate was elected.

In my opinion, the only thing it could possibly change is what the new city councilor thinks of you and your business interests. Politicians can and should refuse donations that come with strings or from unethical sources.

Josh Taylor, the treasurer for Pride PAC II and T-Town PAC II, said in an email that “all contributions to and expenditures from each PAC are properly disclosed and in compliance with the Alabama Fair Campaign Practices Act and are public record available from the Alabama Secretary of State.”

Wilson did not respond to The Crimson White’s requests for comment.

Besides helping politicians pocket thousands of dollars from wealthy donors, laissez-faire campaign finance regulations make it almost impossible for dissatisfied voters to enact meaningful change.

On the rare occasion that a sitting city councilor is ousted, voters will find the same monied interests backing the new candidate. Freshman City Councilor John Faile, dubbed a “political newcomer” by Tuscaloosa News, was supported by the same PACs and businesses that bankrolled just about every other candidate: United PAC, BIZPAC, Pride PAC II and Weaver Rentals.

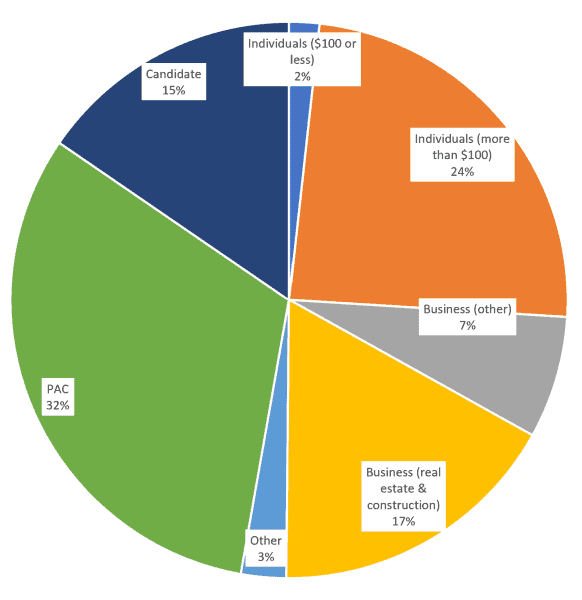

Even though a fair percentage of donations in the 2021 City Council races were from individual donors, the average donation from an individual was $429.74. People able to donate hundreds of dollars to a candidate for City Council simply aren’t representative of the wider Tuscaloosa population.

For voters and not wealthy political donors to pick Tuscaloosa’s City Council, we need campaign finance reform. But if campaign finance regulations with real teeth could even get passed when Alabama politicians love their corporate cash so much, they’d have to pass scrutiny with a Supreme Court irrationally squeamish about public election financing and limits on campaign contributions.

The Supreme Court has made it more than clear in recent years that it thinks any attempt to help grassroots candidates compete with corporate stooges is unconstitutional, unless it stops corruption. At the same time, the court has been gradually redefining corruption and making it easier for venal public officials to stuff their pockets, all while justices treat themselves to free trips on billionaires’ private jets and yachts.

Thanks to the Supreme Court, Seattle, Washington, and Oakland, California, have had to pioneer a new way to help candidates compete with corporate cash. Both cities are giving residents free vouchers to donate to local political campaigns. Candidates can cash in these vouchers to run campaigns without begging for donations from local businesses and PACs.

This is an obviously flawed solution, but we desperately need to do something, anything, about the campaign finance status quo. Right now, to fund a competitive campaign candidates need tens of thousands of dollars from businesses, PACs and wealthy donors, and voters are supposed to just naively assume this won’t affect their decisions once in office.

Are the businesses donating tens of thousands of dollars to Alabama’s politicians really just expressing principled political preferences? Or do they want a quid for their quo, a public contract for their metaphorical gold bars, a license to pollute for their $235,000?

Michael Echols said it best: “Do people expect anything in return for making contributions? If they don’t, I’m proud of them.”