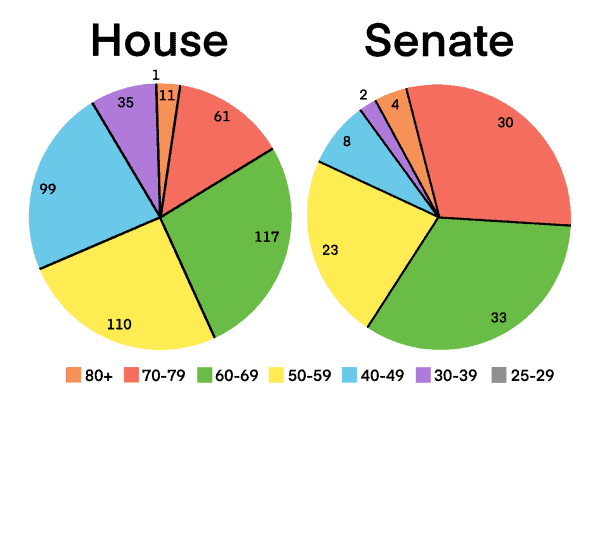

America is a gerontocracy. According to Pew Research Center, the median voting House member is 57.9 years old and the median senator is 65.3 years old.

President Joe Biden is 80, and if he’s reelected in 2024, he’ll leave the White House in 2029 at the tender age of 86. The presumptive 2024 Republican nominee, former President Donald Trump, is 77. If he is elected in 2024, he’ll be 82 when his second term ends.

While the U.S. Census Bureau reports that the age of the median American is slowly rising, it’s still only 38.9 years old. Both of the current frontrunners for the major party nominations in 2024 will be more than twice the age of the average American during the 2025-2029 term.

However, it’s Sens. Dianne Feinstein, 90, finishing out her fifth and final full term, and Mitch McConnell, 81, in the middle of his seventh term, who’ve drawn the most attention for their age.

According to many inside sources, Feinstein, D-Calif., is basically being puppeteered by her staffers, often unaware of where she is and what’s going on. On the opposite end of the country and the political spectrum, McConnell, R-Ky., has frozen and been completely unable to speak during live press conferences twice now.

Because these high-profile politicians are visibly struggling due to their age, people have redoubled their calls to impose term limits on Congress. But this myopic focus on term limits, and age limits, as the solution to gerontocracy tellingly exemplifies the celebrification of American politics.

Politics and politicians matter only because of their effects on public policy. How old a politician is matters only if it affects how they vote.

If it takes “Weekend at Bernie’s”ing a literal corpse out onto the Senate floor to pass “Medicare for All” or the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, sling that body over my shoulder.

This doesn’t mean representation is irrelevant. Being a member of a minority group can provide special insights into specific policy problems facing that group. What it does mean, however, is that American politics wouldn’t be fixed by kicking representatives from solid red and solid blue districts and states out of Congress every few election cycles and replacing them with nearly identical Republicans and Democrats, respectively.

Modern American politics revolves around individual politicians and not political parties because our political parties are far too weak. The offloading of the nomination process to primaries in the 1970s and the fundraising process to candidates (through platforms like ActBlue and WinRed) means the Democratic and Republican Parties can’t control who gets elected as a Democrat or as a Republican.

At face value, this seems more democratic than party insiders picking candidates in smoke-filled rooms, but it means parties can’t discipline elected officials who sabotage party priorities. In “party list” systems where party leadership picks who’s on the ballot, elected officials who vote against party principles lose their nomination.

In 2017, Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., was the decisive vote against the Republican effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act. If he hadn’t died in 2018, the Republican Party would have been powerless to stop him from running and winning again in 2022.

Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., has consistently been stonewalling President Biden’s environmental and pro-labor legislative efforts. Even though prostrating himself at the feet of Big Coal probably isn’t enough for Manchin to be reelected in a state where Trump won 68.62% of the vote, the Democratic Party is basically incapable of punishing him while he’s still in the Senate.

The weakness of both major American political parties means that even if a resounding majority of American voters support either party, it’s likely that party succumbs to factionalism and fails to pass the legislation its mandate demands.

If we really want to see the proposed legislation that inspires us to vote get passed, then we need stronger parties, not term limits. What matters isn’t who the 218 votes in the House are, or who the 51 or 60 votes in the Senate are, but if political parties can whip up those votes.

If you really do care about the age of politicians, though, you still shouldn’t support term limits. You should support making elections far more competitive.

Politicians get reelected dozens of times because they represent “safe” districts or states where one of the major parties is basically a nonentity. If we want real turnover in these districts and younger candidates to get elected, we need competitive elections.

This could mean changing to ranked-choice voting (like in Alaska and New York City), where you rank candidates by how much you want to see them elected, or it could mean adopting approval voting, where voters can vote for every candidate they support. Ideally, though, it would mean switching to proportional representation, and every party would get the same percentage of elected officials as they got votes.

By making third parties competitive, electoral reform in combination with public election financing would stop Democrats and Republicans alike from squatting in safe seats for decades. The Democratic and Republican parties would actually have to worry about more than just the handful of swing races.

Term limits would just mean milquetoast politicians get replaced with cookie-cutter copies every few elections. If we want public policy to actually reflect the will of voters, we don’t need half-hearted reform.

We need to make politicians accountable to their parties and parties accountable to voters.