Opinion | Condemning UA’s relationship to Aramark

February 2, 2023

The latest string of prison strikes within the Alabama Department of Corrections, beginning in late September 2022 and subsiding in mid-October, has reanimated conversations regarding the treatment of inmates — conversations that had previously remained dormant in the public consciousness.

The cries for justice from inmates incarcerated in the ADOC are not new. In 2017, the grassroots organization Free Alabama Movement launched a protest campaign against Aramark, the University’s primary dining service provider. At the time, they pointed toward Aramark’s relationship to prison labor, listing complaints ranging from the mistreatment of inmates on the part of supervisors to the provision of undercooked food.

Aramark, a multi-billion dollar company, does not compensate inmate kitchen workers with a proper wage. According to Aramark, the responsibility of just compensation should fall on corrections; however, amid a lawsuit levied against Aramark and Alameda County, the county suggested that if any institutions were to pay proper wages, it should be Aramark. Regardless of which entity should be the one to pay real wages, Aramark is still clearly embedded in a system that benefits from captive labor.

The use of prison labor in this country is not a new phenomenon. Pioneered by the likes of John W. Comer, this pernicious form of labor was allowed to persist as the consequence of a loophole in the 13th amendment to the constitution.

While the Convict-Lease System was formally disbanded in 1928, the principle of using virtually free prison labor found a home in the modern prison-industrial complex. The language of this practice has been obscured, couched in euphemisms to elude scrutiny from the public eye, but it persists nonetheless.

In addition, the University already has a long and personal history of slavery. If the University is to reconcile with its history, it would behoove the administration to look closely at its relationships with companies that still have their hands in correctional departments across the country. The administration has already made a conscious effort to remove racist namesakes from campus, but it’s time we shift from symbolic gestures to addressing ongoing, tangible processes.

In most states, prisoners are paid pennies an hour. These pennies are often recycled into the prison system via facilities charging prisoners for things like toilet paper and medical co-pays. Many inmates in Alabama receive no compensation for their work, and the refusal to do so runs the risk of enduring solitary confinement or some other form of punishment.

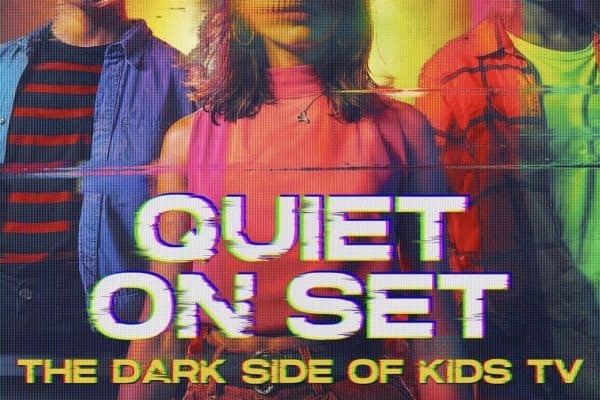

Universities across the country, including The University of Alabama, contract their dining services out to Aramark. Pressure from student activist groups has led some universities, like the University of Florida, to cut ties altogether. Other schools have proven that the University is capable of not giving business to a company that generated around $1.5 billion in revenue from its work around prisons in 2020. When universities work with companies entrenched in prison labor, they indirectly sustain the practice itself.

In response to our inquiries, Heather Dotchel, who manages Aramark’s corporate communications, laid out the company’s policies.

“Aramark proudly serves individuals who are justice-impacted in the United States in both the food service and commissary spaces,” Dotchel said.

To Aramark, serving “justice-impacted individuals” appears to mean using them for unpaid labor and working with correctional departments to classify inmates as students for profit. Via the IN2WORK program, Aramark, in coordination with correctional facilities across the country, frames the labor of inmates in kitchens as an educational opportunity rather than a form of employment, thus relieving them of the responsibility of placing them on the payroll.

While Aramark is not the primary food service provider for the ADOC, Dotchel did not deny its involvement with some correctional facilities in Alabama.

By disguising prison labor as a learning experience rather than employment, they are able to circumvent calling their company what it is — a multi-billion dollar corporation with a relationship to modern-day slavery.

Dotchel elaborated that they have staff members in correctional facilities who often work alongside “justice-impacted individuals” who are designated by corrections agencies to work in kitchens.

“Corrections agencies — not Aramark — provide assignments to incarcerated individuals such as landscaping, laundry, and kitchen work, as well as determine any compensation they receive,” Dotchel said.

But despite not being specifically delegated the power of assigning work to individuals, their complicity undeniably abets the use of prison labor.

In a country where poverty is criminalized and justice is conceived through the lens of punishment rather than reform, it is little wonder that the United States has the highest prison population in the world. Yet there is still hope, because in America, the buck stops with the consumer, and for many, the grapes of mass incarceration have begun to sour.

As students of the University, it is imperative that our investment in this institution comply with the conscience of its student body, which means demanding our alma mater cuts ties with an industry enmeshed with the practice of involuntary servitude.