‘Stepping into battle’: The state of women’s safety

Courtesy of Women of Excellence

Women of Excellence is a student organization dedicated to empowering African American women.

February 2, 2022

The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women recently published a study that found that 97% of the women surveyed had experienced some form of sexual harassment.

After the research was published, “97%” became the label of a viral internet movement to raise awareness for women’s right to safety in the public sphere and to push for the end of sexual harassment. Women started using the hashtag #97percent in TikTok videos to share their stories of sexual harassment and sexual violence, and in Instagram posts where users linked women’s rights charities and organizations.

The harsh reality in the 21st century is that while women have achieved a form of equality in terms of written legislation, they are far from achieving it in practice, as they are socially and economically inferior to their male counterparts.

One of the most brutal ways this inequality manifests is in women’s lack of public safety.

“I try to never walk anywhere alone, especially at night and if I am walking somewhere alone, to my car or even on campus, I try to be on the phone with a friend or my mom or someone,” said Fatema Dhondia, the former president of the United Greek Council and a junior majoring in mechanical engineering and German.

Many women are able to rattle off a laundry list of precautions they take throughout the day to stay safe: Check underneath cars and backseats before driving anywhere; remove identifying stickers and pins from cars and backpacks; hold house keys between knuckles when walking through a parking garage.

Jennifer Purvis, the University of Alabama women’s studies director, said experiencing sexual harassment and the constant need to stay alert factor into women’s sense of well-being and even their personalities.

The University of Alabama offers organizations, resources and programming aimed at protecting women. Dhondia has invited a plethora of speakers to give presentations to her and her sorority sisters about tips to stay safe, the warning signs of human trafficking, how to react in possibly dangerous situations and more.

The University even offers a three-credit kinesiology course in self-defense for female students called KIN 155, Self Defense for Women.

The course’s purpose, according to the UA course catalog, is “to provide the student with the knowledge and skills that will enhance the student’s ability to defend herself in case of physical or sexual assault as well as to enhance her overall personal safety.”

The course is open to students of any major, and no prerequisites are required.

“Taking [KIN 155] is one of the best decisions I’ve made. I learned so many tips and skills that I will utilize throughout the rest of my life,” Dhondia said. “I recommend every female student take this class if she has the chance.”

Dhondia said she and her sorority sisters appreciated the education and the support, but they are left frustrated that women have to be briefed as if stepping into battle when they are taught simply how to exist in public.

They are not entering the battlefield unarmed. The market today is overwhelmed with gadgets and inventions advertised to aid women’s safety. Women will carry lipstick tasers and pink pepper sprays, wear nail polish that detects date rape drugs, don scrunchies that can be used to cover their drinks, grip brass-knuckle keychains, snap-on alarm bracelets and more.

Purvis said solutions that address the actions of the victim and not the aggressor will never solve the core issues from which these problems stem.

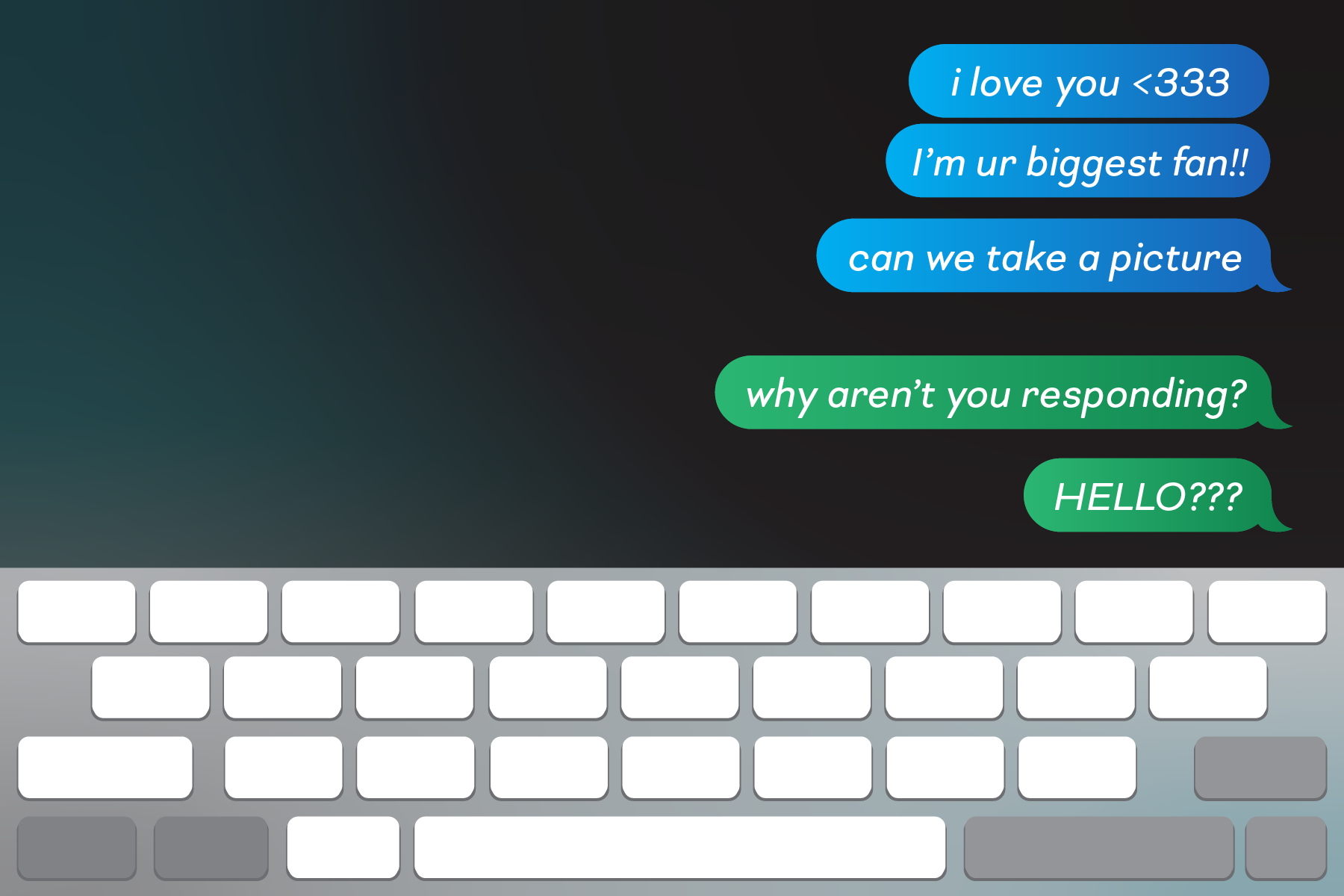

These safety measures are taken to an even greater degree in the context of parties.

“All [women] know the most important thing is to never be alone,” said Dezirae Cunningham, the president of the UA student organization Women of Excellence and a senior majoring in public health. “You have to have people around you, watching out for you, making sure you never walk anywhere by yourself, and that there aren’t people taking advantage of you if you happen to be drinking. We, as women, aren’t really ever allowed to relax.”

Bars recognize the dangers women face and have implemented measures to protect them, such as the Angel Shot, which isn’t an actual drink, but a sort of code word that women can use to alert bartenders that they are uncomfortable or in danger. The bartender can take appropriate action — intervening, calling the police or removing the patron making the woman feel unsafe. Several bars have security personnel who will walk women to their cars if they request it.

Dhondia said the UGC regularly informs its members of these resources available to them.

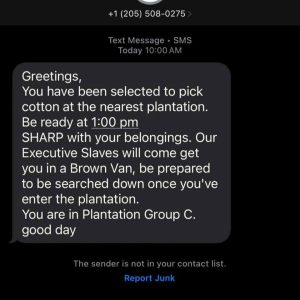

Many sororities make sure their members know safety protocols, such as never leaving drinks unattended, never accepting an open beverage, drinking out of bottles or cans when possible, and covering the openings of drinks.

Spiking is a well-known danger to women, especially on and around college campuses.

The American Psychology Association found that almost 8% of students surveyed across three major universities reported having been drugged via a drink at some point. The study also said that “women were more likely to report sexual assault as a motive while men more often said the purpose was ‘to have fun.”

“I think that at the root of solving this problem is to educate both men and women about the issues women face,” Cunningham said.

Purvis said the only way to see lasting reform is to overhaul sex education in the United States, because comprehensive sex education is one of the best tools in the fight for justice for women, and it is severely underutilized.

When conscious work isn’t done to change the cultural climate that demands women live in these conditions, the consequences are deadly.

Prolific violence against women is a cultural truth every woman has been prepared for since a young age. However, the media and popular culture do not treat all crimes against women the same and do not necessarily treat those they do choose to cover in a sensitive manner.

According to an article by NPR, “tens of thousands of Black girls and women go missing every year. Last year, that figure was nearly 100,000.” These cases are rarely featured in national headlines.

“Missing white woman syndrome” refers to the mass hysteria that takes hold of Western media when an attractive white woman goes missing– the attention and concern that is suspiciously absent from the news when women of color disappear in similar cases. The phenomenon is meant to highlight the objectification of women, the desensitization of the public to violence against women and the discrimination faced by women of color.

“It’s honestly exhausting to be a woman who already doesn’t feel safe, but on top of that to know that no one would say anything if something were to happen to me,” Cunningham said.

These ideas were recently reignited when news of Lauren Smith-Fields’ death and her family’s subsequent lawsuit against the city of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was made public.

Smith-Fields was 23 years old when she was found dead in her apartment, and the last person she was known to be with was an older white man she had met on the dating app Bumble. The man was not considered a suspect and was not investigated in Smith-Fields’ disappearance and death.

Smith-Fields’ family is now suing the city of Bridgeport for “failure to prosecute and failure to protect under the 14th Amendment.”

“Missing white woman syndrome” and Smith-Fields’ death serve to reemphasize the importance of intersectionality in modern feminist movements.

“Intersectional feminism illuminates the connections between all fights for justice and liberation. It shows us that fighting for equality means not only turning the tables on gender injustices but rooting out all forms of oppression,” an article published by UN Women said. “It serves as a framework through which to build inclusive, robust movements that work to solve overlapping forms of discrimination, simultaneously.”

The Alabama chapter of United for Reproductive & Gender Equity holds this idea central to its mission as it fights for reproductive justice in the United States. In addition to engaging in activism for women’s rights, the chapter also speaks about racial justice and justice for the LGBTQ community, including achieving accessibility to comprehensive health care for all individuals.

Reproductive justice demands intersectionality because of the consequences of a lack of reproductive rights.

On Dec. 1, the Supreme Court heard the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The case surrounded a Mississippi law that would ban abortions after 15 weeks. The decision would potentially undermine and lead to the overturning of Roe v. Wade, the landmark Supreme Court case that protects pregnant people’s bodily autonomy and has been used to rule restrictive abortion laws unconstitutional for the past 50 years.

Such a decision would disproportionately affect socioeconomically disadvantaged and minority communities. According to research from the Guttmacher Institute, restrictive laws against abortion do not stop abortions but rather reduce women’s access to safe abortions.

“The data shows that abortion rates are roughly the same in countries where abortion is broadly legal and in countries where it isn’t,” Zara Ahmed, an associate director of federal issues for the Guttmacher Institute, said in an article for NBC.

Beyond the debates of the morality of abortion lies the devastating truth that attempting to force women to carry pregnancies to term only serves to harm the mother, the child and the communities they are a part of.

“We don’t have child care services in high schools and colleges or a lot of services available, so people … are going to have to quit college or in some cases be kicked out of their families,” Purvis said. “It would be disastrous, especially because there’s not the support there.”

Research from the Pew Research Center found that a majority of the American public supports abortion rights. Purvis explained that, should Roe v. Wade be overturned in 2022, she believes that the U.S. population would not be silent and that the decision would not last long.

Purvis said she doesn’t know how it would manifest, but she doesn’t believe society would allow it to stand.

URGE is one of several organizations across the country mobilizing people in the fight for reproductive rights.

“URGE does sex education and sexual assault awareness programming, we provide information for health care access, we distribute Plan B and condoms when needed, we write letter campaigns to policymakers,” said Sarah Lib Patrick, the president of URGE UA and a senior majoring in restorative justice and civil rights studies.

Purvis said women and young activists should “demand better.”

This story was published in the Justice Edition. View the complete issue here.

Questions? Email the Culture desk at [email protected].